The case for closer economic union has become more compelling as external challenges multiply

Europe faces the most daunting set of challenges since the Cold War. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the first major war of aggression on European soil since 1945, has forced a fundamental questioning of old certainties. Geopolitical ructions have shaken supply chains, disrupted trade, and exposed serious energy-security vulnerabilities. The transatlantic alliance, which has provided security for the past 80 years, is under pressure. Europe is committed to increasing defense spending to fend off foreign foes but must also protect the public services and welfare systems that underpin its social contract.

These challenges would be much simpler to resolve if economic growth were strong and public money plentiful. But Europe’s postpandemic recovery has run out of steam, and stagnant productivity is dragging down medium-term growth prospects. Countries face significant strains on public finances, with rising spending pressures. Exporters face stiff tariffs to sell goods to their most important foreign market, the United States. Moreover, Europe’s working-age population is set to shrink by 54 million by the end of this century, making it all the harder to generate growth and lift living standards.

Yet, if history is a guide, Europe can turn adversity to advantage. After World War II, European nations faced the monumental task of rebuilding their economies, restoring political stability, and preventing future conflict. They met these challenges through economic integration and political cooperation, aspiring to the free movement of goods, services, people, and capital across borders. This unique historical experiment, which later developed into the European single market, stemmed from a core belief: Stronger economic connections between nations bring peace, prosperity, and stability.

Postwar reconstruction played an essential part. The Marshall Plan may be better known, but other initiatives—the European Payments Union of 1950 and the European Coal and Steel Community of 1952, for instance—proved equally pivotal. They established essential foundations and strengthened cross-border cooperation. By 1957, six nations had formed the European Economic Community, putting the continent on a path toward the single market.

Eighty years on, the single market has made remarkable strides. Comprising 27 nations and 450 million people, it lies at the heart of the European Union. And it has turned the EU into a global economic powerhouse, accounting for about 15 percent of world GDP in current US dollars, comparable only to the US and China. This prosperity has not come at the expense of its core values or quality of life. Today, many European nations rank high in life satisfaction, safety at work, social protection, and life expectancy. And Europe has continued to put a strong emphasis on international cooperation, be it in trade or climate policies, even during the most trying times.

Yet the single market remains incomplete. Its full economic potential is limited by persistent barriers and national priorities in some sectors and industries (see “Europe’s Future Hinges on Greater Unity” in this issue of F&D). Moving toward a shared form of economic and political sovereignty is never easy—nor should it be. Indeed, this is the main reason the single market has always been seen as a work in progress. Strategically important sectors—energy, finance, and communications—were excluded from full integration from the start. But as recent reports by former Italian Prime Ministers Mario Draghi and Enrico Letta make clear, the case for completing and deepening the single market has become even more compelling as external challenges multiply. Europe needs more growth and more economic resilience. A more fully integrated economy can deliver both.

The EU has made significant progress freeing up trade between its member states, but plenty of obstacles remain. High trade barriers within Europe are equivalent to an ad valorem cost of 44 percent for manufactured goods and 110 percent for services, IMF research shows (2024). These costs are borne by EU consumers and companies in the form of less competition, higher prices, and lower productivity.

The EU is also a long way from capital market integration, with cross-border flows frustrated by persistent fragmentation along national lines. The total market capitalization of the bloc’s stock exchanges was about $12 trillion in 2024, or 60 percent of the GDP of the participating countries. By comparison, the two largest stock exchanges in the US had a combined market capitalization of $60 trillion, or over 200 percent of domestic GDP. Limited EU-level harmonization in important areas, such as securities law, hampers growth by preventing capital from flowing to where it’s most productive.

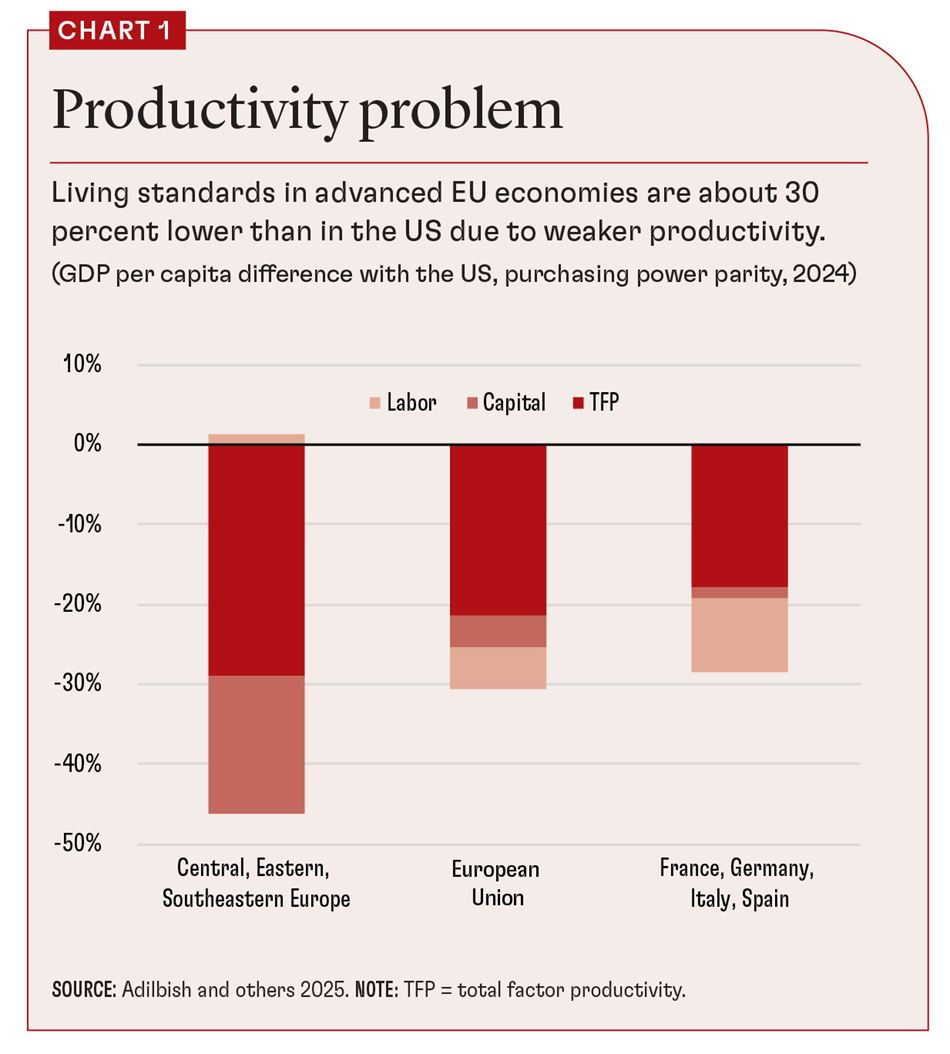

This is one reason Europe has fallen behind in the adoption of productivity-enhancing technologies and its productivity levels are low. Today, the EU’s total factor productivity is about 20 percent below the US level. Lower productivity means lower incomes. Even in the EU’s largest advanced economies, per capita income is about 30 percent lower than the US average (see Chart 1).

Low-growth firms

Europe’s wide productivity gap warrants a closer look. My colleagues recently examined the performance of European companies with the potential to become macroeconomic growth engines—established productivity leaders as well as young high-growth firms (Adilbish and others 2025). The findings reveal significant innovation and productivity gaps relative to the global frontier for both groups.

Not only do Europe’s leading companies lag their US competitors, but they are falling further behind over time. This is true across all sectors, but especially for tech. While the productivity of US-listed tech firms has increased by about 40 percent over the past two decades, European tech firms have seen almost no improvement.

One reason could be that US firms are simply trying harder: They have tripled their research and development spending to 12 percent of sales revenue, three times European companies’ ratio, which has languished at an average of 4 percent in recent decades.

The future would look brighter if Europe could hope for young high-growth firms to reduce the innovation and productivity deficit. Alas, the EU has few such companies. And they have a substantially smaller economic footprint than those in the US, where younger firms account for a far larger share of employment.

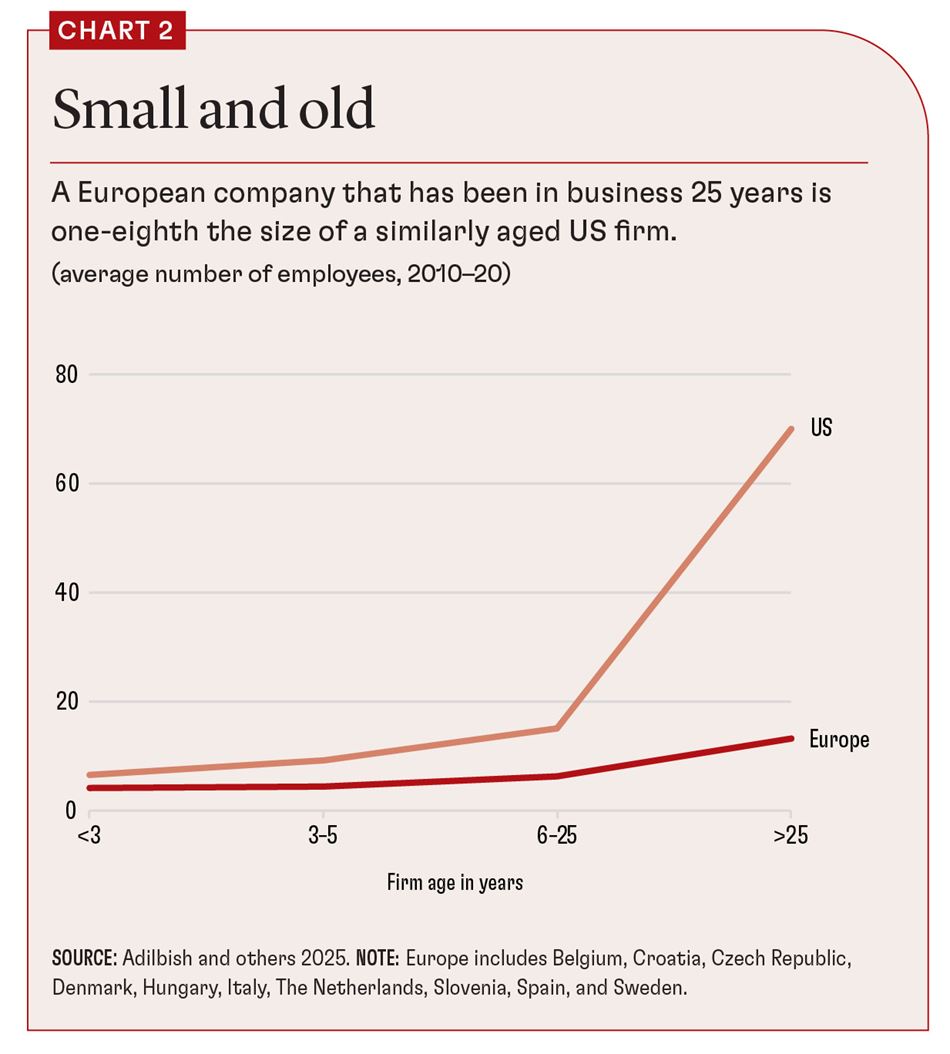

In other words, the EU has too many small, old, and low-growth companies. About a fifth of European employees work in microfirms with 10 people or fewer, about double the US figure. And while the average European firm that has been in business 25 years or more employs about 10 workers, comparable US companies employ 70 (Chart 2).

What explains these stark differences? Our research points to Europe’s still-fragmented consumer markets for goods and services. But capital and labor markets are also at fault, further limiting companies’ incentives to scale up and their abilities to do so.

Europe’s bank-dominated financial markets favor physical collateral for their loans. But young companies, especially in the tech sector, typically have fewer physical and more intangible assets, such as patents. The continent needs capital markets to channel savings into large-scale long-term investments in risky but potentially revolutionary ideas.

Scarcity of high-skilled workers is another problem. This reflects both high barriers to cross-border labor mobility and the overall lack of human capital needed for innovative sectors. This is compounded by many countries’ aging populations, which could make the new ideas that produce young and high-growth firms harder to come by.

Stronger single market

For now, at least, Europe’s productivity gap does not stem from a shortage of innovative ideas. It remains an important incubator for innovation in foundational science and technology, and its companies continue to push the intellectual frontier, especially in fields like pharmaceuticals and bioengineering (see “Europe’s Innovators Are Waking Up” in this issue of F&D). Even so, there is a troubling trend of innovative European firms taking their talents to more dynamic markets elsewhere, with future “unicorn” companies valued at more than $1 billion leaving the EU for the US at a rate that is 120 times faster than the other way around, according to research by Ricardo Reis, of the London School of Economics.

Europe certainly has enough savings available to finance higher investment. At about 15 percent of GDP, the EU’s household saving rate is about three times that of the US. Yet Americans invested $4.60 in equity, investment funds, and pension or insurance funds for every dollar invested in such assets by Europeans in 2022. The fundamental issue is the EU’s more limited ability to channel ideas and capital into productive uses within its borders. Put simply, the continent’s fragmented internal market has failed to realize a lot of income growth.

All this underscores the urgency of completing the single market agenda. Sound macroeconomic policies, including securing price stability to provide certainty to investors and meeting spending challenges without upending fiscal sustainability, are necessary preconditions. Next, countries must step up reforms in the core areas of the single market.

Lowering internal trade barriers, in goods and especially in services, must be a priority. It would incentivize firms to undertake R&D and other high-risk, high-reward investments. The EU could raise its GDP by 7 percent if it reduced internal barriers for goods trade and multinational production by 10 percent, our research shows. There is plenty of room for improvement by opening protected sectors, liberalizing services, and harmonizing regulations.

These efforts must be accompanied by progress toward an integrated capital market, or savings and investments union (see “Europe’s Elusive Savings and Investment Union” in this issue of F&D). Critical reforms—including reviewing the prudential regime for insurers and harmonizing oversight of capital markets—could channel the EU’s substantial savings into much-needed equity financing for all companies.

Young high-growth firms would benefit significantly from the greater availability of capital and lower financing costs—capital that market integration could deliver, especially if paired with national reforms to unleash venture capital investment.

At the same time, countries must be careful not to undermine the single market and all its opportunities with poorly conceived industrial policy. Industrial policy can play a role if it corrects market failures—by pushing companies to become greener or to take up transformative technologies, for example. But protecting mature industries from sweeping structural transformation is not sensible. Europe must look forward, not backward.

Even carefully targeted industrial policy can backfire by diverting trade and production patterns away from established areas of comparative advantage. Countries must coordinate industrial policies or, better still, agree to set them at the EU level (Hodge and others 2024).

Greater resilience

A fully integrated single market would also strengthen Europe’s economic resilience in today’s perilous, shock-prone world. Companies that serve more customers in more countries are less affected by economic ups and downs at home. The same principle applies to personal investment portfolios when financial market barriers are lowered and people spread their holdings across the whole EU. The benefits of risk sharing can be sizable, but diversification is still limited compared with the US.

Similarly, the EU could reduce its dependence on imported oil and gas, protect itself from volatile global energy markets, and lower prices for consumers with a more integrated energy market.

To take full advantage of EU reforms, national efforts must match regional ambition. Labor markets, human capital, and taxes are in the greatest need of reform to promote growth, our forthcoming research shows. Advanced economies would benefit most from deregulating product markets, deepening credit and capital markets, and promoting innovation. For many central, eastern, and southern European countries, the top priorities are investing in skilled labor, removing red tape, and improving governance. The growth gains could be sizable.

Power of integration

The 2004 enlargement welcomed Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, the Slovak Republic, and Slovenia to the EU. Two decades later, GDP per person in those countries is more than 30 percent higher than it would have been without accession. For the countries already in the EU, GDP per person is 10 percent higher than it would have been without expansion (Beyer, Li, and Weber 2025).

This leap in living standards underscores the powerful impact of integration. Current reform proposals are a start, but more ambition is needed. A stronger single market would improve the EU’s economic outlook, support its policy priorities, and strengthen its resilience, ensuring that the region remains a global leader in innovation, sustainability, and quality of life. It’s an opportunity Europe cannot afford to squander.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.

References:

Adilbish, O., D. Cerdeiro, R. Duval, G. Hong, L. Mazzone, L. Rotunno, H. Toprak, and M. Vaziri. 2025. “Europe’s Productivity Weakness: Firm-Level Roots and Remedies.” IMF Working Paper 25/40, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

Beyer, R., C. Li, and S. Weber. 2025. “Economic Benefits from Deep Integration: 20 Years after the 2004 EU Enlargement.” IMF Working Paper 25/47, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

Hodge, A., R. Piazza, F. Hassanov, X. Li, M. Vaziri, A. Weller, and Y. Wong. 2024. “Industrial Policy in Europe: A Single Market Perspective.” IMF Working Paper 24/249, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2024. Regional Economic Outlook for Europe: A Recovery Short of Europe’s Full Potential. Washington, DC, October.