An integrated capital market must be accompanied by regulatory reforms to attract substantial investment

Europe has ample savings but not enough investment. A savings and investment union (SIU)—a pan-European financial market that mobilizes and makes savings available for investment across the European Union—is part of a long-term remedy.

But it will take more than that to generate the amount of investment the EU needs to meet its growth and geopolitical challenges. A single financial market must be able to offer attractive investment returns. That requires less red tape and uniform regulation across EU states, which will lower trade barriers between them.

The push for a continent-wide capital market is not new. An earlier initiative, launched in 2015 as the EU Capital Markets Union, turned out to be politically contentious. Now, the idea has renewed impetus following reports in 2024 by former European Central Bank President Mario Draghi and former Italian Prime Minister Enrico Letta and the European Commission’s March 2025 publication of its SIU strategy.

An integrated financial market would complement the single market in goods and reduce the dominance of bank financing in favor of more long-term capital market financing for investment, as in the United States. The various proposals (and the Commission’s latest communication, which builds on them) comprise tackling a long list of specific barriers to a unified market. These proposals command much support among technocrats and markets, but with little progress to show so far. This is amply illustrated by one of the key obstacles to an SIU: The EU banking union, launched after the 2008 global financial crisis, remains incomplete.

A larger pool of savings available across the EU is necessary to increase private investment. As the Draghi report notes, about 80 percent of productive investment has historically come from the private sector. And this private contribution is even more pertinent now given the tight fiscal constraints in the largest countries (with the exception of Germany).

Fragmented capital market

Savings in Europe are kept largely in domestic economies, partly because 80 percent are in bank deposits. And banks do not normally lend these deposits across national borders. This pervasive “home bias” of savings and investment (more than in the US) is compounded by regulatory barriers that inhibit greater cross-border financial activity and capital market development.

Europe’s low issuance of securitized assets is a prime example of how the lack of uniform regulation and unnecessarily high capital charges inhibit growth. The underlying assets in any European securitized offering are national and comprise largely residential mortgages. Differences in national regulations make it difficult for issuers to package EU-wide mortgages in one security.

Institutional holders such as pension funds and insurance companies also limit their holdings because of high capital charges imposed by the regulator, the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority. The net effect is low issuance, and assets that could easily be sold into capital markets remain instead on bank balance sheets. Regulatory differences, moreover, exacerbate home bias among institutional investors. Similarly, pensions are not portable across the EU when people take jobs in another member state, confining investment within national schemes.

Fragmentation has real costs. It results in substantial variation in borrowing costs for households and especially small and medium-sized businesses. This variability across national boundaries results partly from the relationship between bank funding costs and the funding cost of the sovereign government (because bank resolution is still largely national). But it also stems from the lack of competition in European banking.

The variability in lending margins declined following the European Central Bank’s large-scale targeted liquidity provision, but it is still higher than it was before the global financial crisis, even though the divergence in government bond yields has subsided. More uniform bank funding is particularly important for small and medium enterprises because many would not meet the requirements for market funding, and many might not want to give up control.

This points to the central role for banks in an SIU. Large banks in the US have more than 60 million customer accounts each—no European bank comes close—and therefore benefit not only from economies of scale but also important synergies from marketing many different products. With bank resolution still the responsibility (and under the purview) of EU member states, banks’ activities remain largely national, with limited cross-border flows of bank liquidity. This limits the growth of both pan-European savings products and investment instruments that span national borders—such as, for example, mortgages and securitized loans.

As in the US, banks are essential for capital market development, something the European Commission’s SIU strategy underscores. Banks issue securities, act as intermediaries for investors, and are investors and liquidity providers themselves. Thus, the unfinished banking union is unquestionably holding back progress toward a pan-European capital market. Even if common resolution is difficult, allowing more cross-border mergers and letting banks move liquidity where they deem returns to be reasonable would be a good start.

Equity capital is also more expensive than in the US. This reflects, among other things, a much larger US market, compared with Europe’s fragmented, and still largely national, market. Moreover, the EU’s bank-based system is not well suited to providing innovators sufficient capital to start up and then scale up. The value of start-ups that develop new technologies and business models is often in intangible capital, which banks typically do not finance because of insufficient collateral. This points to a need for venture capital.

But according to IMF calculations, venture capital funds raise seven times more in the US than in the EU, reflecting EU private capital pools being smaller and more fragmented than in the US. As a result, the EU currently is home to less than 15 percent of start-ups valued at more than $1 billion (so-called unicorns). According to the European Investment Bank (EIB), EU scale-up firms raise 50 percent less capital on average than their US counterparts in their first 10 years. Stock market fragmentation also makes growing through initial public offerings (IPOs) in the EU less attractive than in the US, further reducing incentives to invest in EU start-ups. Many are therefore motivated to move abroad to get financing to scale up.

Harmonized regulation

The early designs for what was then planned as the EU Capital Markets Union included more ambitious initiatives: a common insolvency framework across all member states and, the most politically contentious, an EU-issued safe asset, such as its own bond. Many consider such an asset essential for pricing and hedging private risk. Except for one or two bigger members with large debt markets, member states could not provide a safe asset with predictable credit quality. As yet, these ideas remain on the drawing board.

The early plans also included centralizing regulation, with the European Securities and Market Authority (ESMA) acting as the single common regulator for EU financial markets, and setting common reporting requirements for issuers. Progress in this area has been slow, with national regulators required to cede more power to ESMA only gradually. A renewed push in this area following the Commission’s communications and other reports is encouraging, although the differences of opinion among member states haven’t disappeared.

Expected returns drive investment

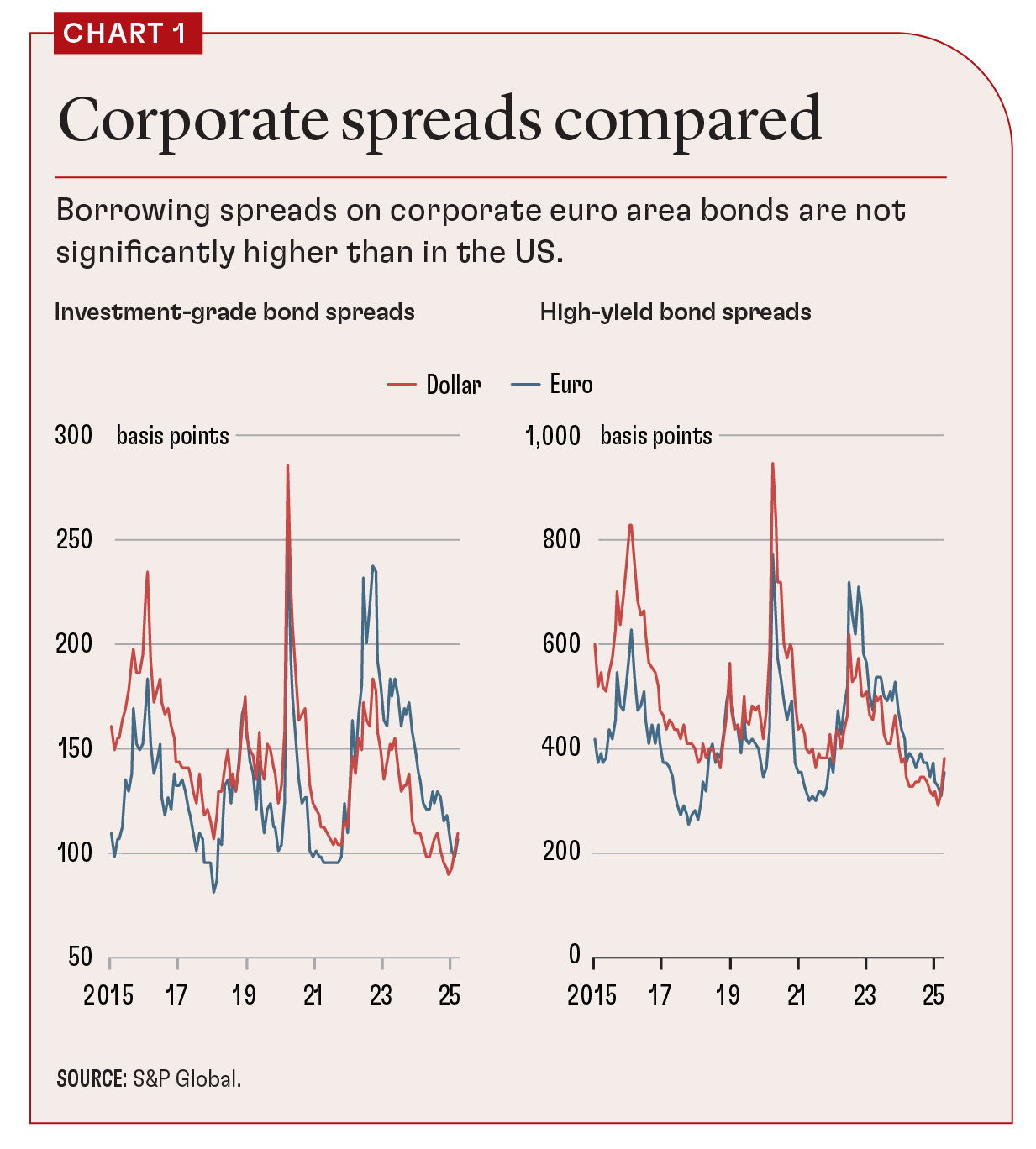

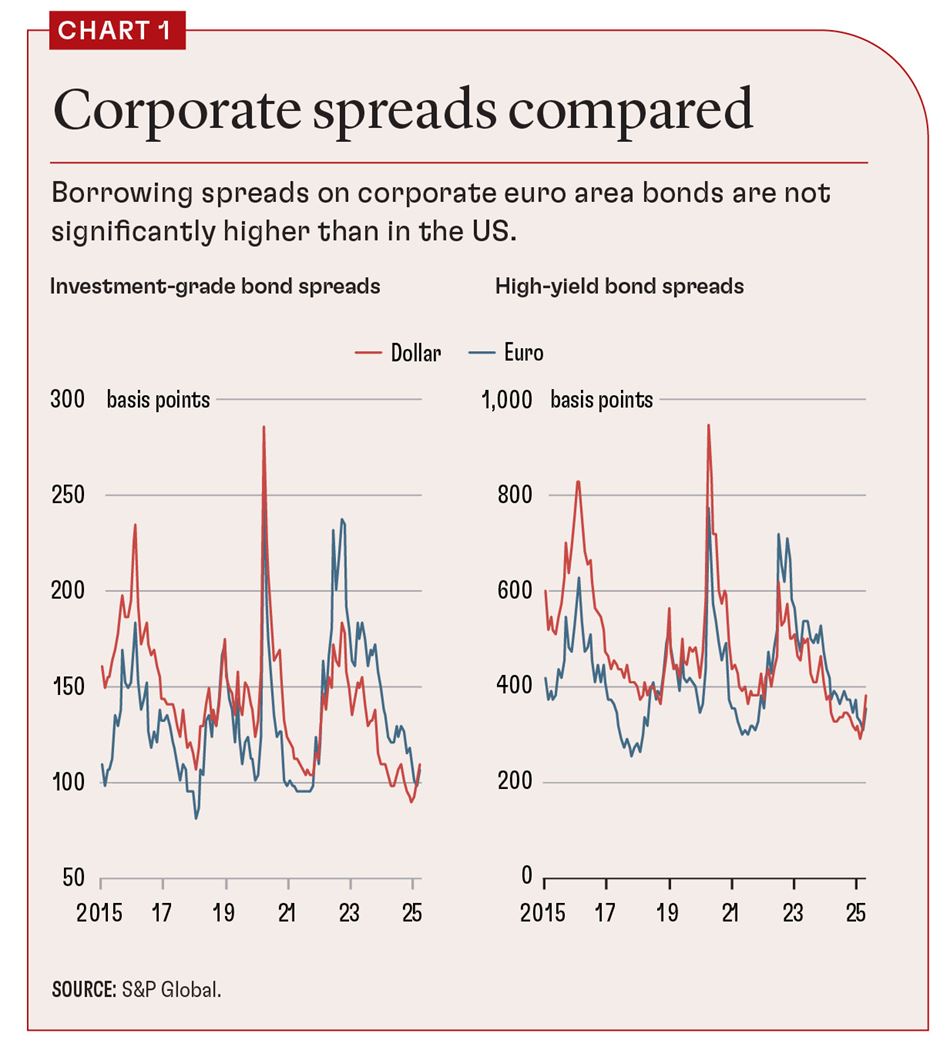

There is also too much optimism about the SIU being the fix for low investment. It is doubtful that an integrated financial market alone could increase investment anywhere close to 5 percent of GDP per year—the shortfall identified by Draghi. The availability of capital, or the dispersion in the cost of capital across the EU, is a drawback. But it is difficult to believe this is the main impediment to investment. For example, spreads on large firms’ borrowing are not significantly higher in the EU than in the US (see Chart 1).

A bigger pool of savings and lower cost of capital are only one side of the equation. Firms will invest more if they expect higher returns, which in turn requires reforms and deregulation that expand their market.

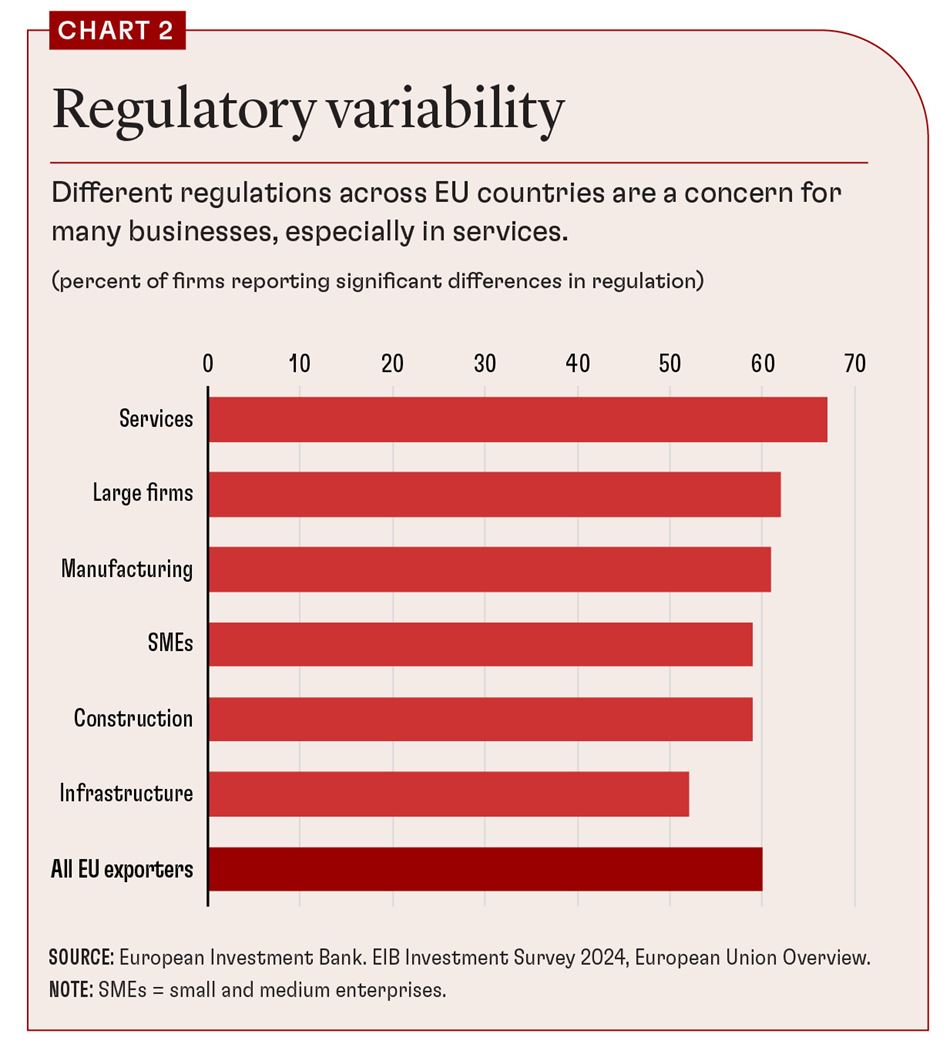

Lack of uniform regulation in the EU single market is an underlying issue that prevents companies from scaling up by expanding into other EU markets. This is likely a more important factor behind the persistent growth divergence between the US and the EU, which manifests itself in lower rates of return on EU investments.

According to EIB surveys, 60 percent of EU exporters and 74 percent of innovators report that they must comply with significantly different regulations across EU countries, with the services sector hit hardest (Chart 2). This reduces intra-EU trade, with IMF estimates suggesting that remaining intra-EU trade barriers are equivalent to an ad valorem tax of 45 percent for the manufacturing sector and up to 110 percent for the services sector, well above levels in US states.

Beyond the costs of intra-EU trade barriers, EU firms face significant costs associated with red tape. According to EIB estimates, the cost of dealing with regulatory compliance is 1.8 percent of sales on average (2.5 percent for small and medium enterprises). By comparison, EU firms’ energy costs have been about 4 percent of sales. The cost of red tape is behind the current EU aim to reduce the reporting burden for all companies by 25 percent and by 35 percent for small and medium enterprises.

Not a panacea

A single financial market would increase cross-border financial flows and reduce the cost of capital. But the limited progress so far points to high political and legislative hurdles. In the many constructive proposals put out recently—largely recycling ideas that have been around for almost 10 years—most of the actions needed are at the member-state level, where there is still much lingering disagreement, such as on completing the banking union and on harmonizing withholding taxes and insolvency regimes.

Even with quick progress on an SIU—a huge ask—it is unlikely to generate enough investment for the EU to meet its growth and geopolitical challenges. In particular, gross rates of return will need to be higher. Moving on the competitiveness and single market agendas quickly is key.

The EU must act on various fronts simultaneously to create a positive feedback loop of lower trade barriers and less red tape, higher rates of return, more unified financial regulation and supervision, and fewer impediments to the cross-border movement of capital. It is a formidable task. But one the EU must overcome to counter increasing growth headwinds.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.