A decline in global population later this century may threaten human progress, or it may lead to better lives

Global fertility rates have been falling for decades and are reaching historically low levels. While the human population now exceeds 8 billion and may top 10 billion by 2050, the momentum of growth is dissipating because of declines in its most powerful driver—fertility. Over the next 25 years, East Asia, Europe, and Russia will experience significant population declines.

What this will mean for the future of humanity is rather ambiguous. On one hand, some fear that it could hinder economic progress as there will be fewer workers, scientists, and innovators. This could lead to a paucity of new ideas and long-term economic stagnation. Moreover, as populations shrink, the proportion of older people tends to expand, weighing on economies and challenging the sustainability of social safety nets and pensions.

On the other hand, fewer children and smaller populations will mean less need for spending on housing and childcare, freeing resources for other uses such as research and development and adoption of advanced technologies. Declines in fertility rates can stimulate economic growth by spurring expanded labor force participation, increased savings, and more accumulation of physical and human capital. Population decline may also reduce pressures on the environment associated with climate change, depletion of natural resources, and environmental degradation.

Clearly, policymakers face crucial choices in managing the unfolding demographic trends. Responses may include measures to encourage fertility, adjustments to migration policies, expansion of education, and efforts to encourage innovation. Together with advances in digitalization, automation, and artificial intelligence, the coming declines in population pose a significant challenge but also a potential opportunity for the world’s economies.

Fertility rates

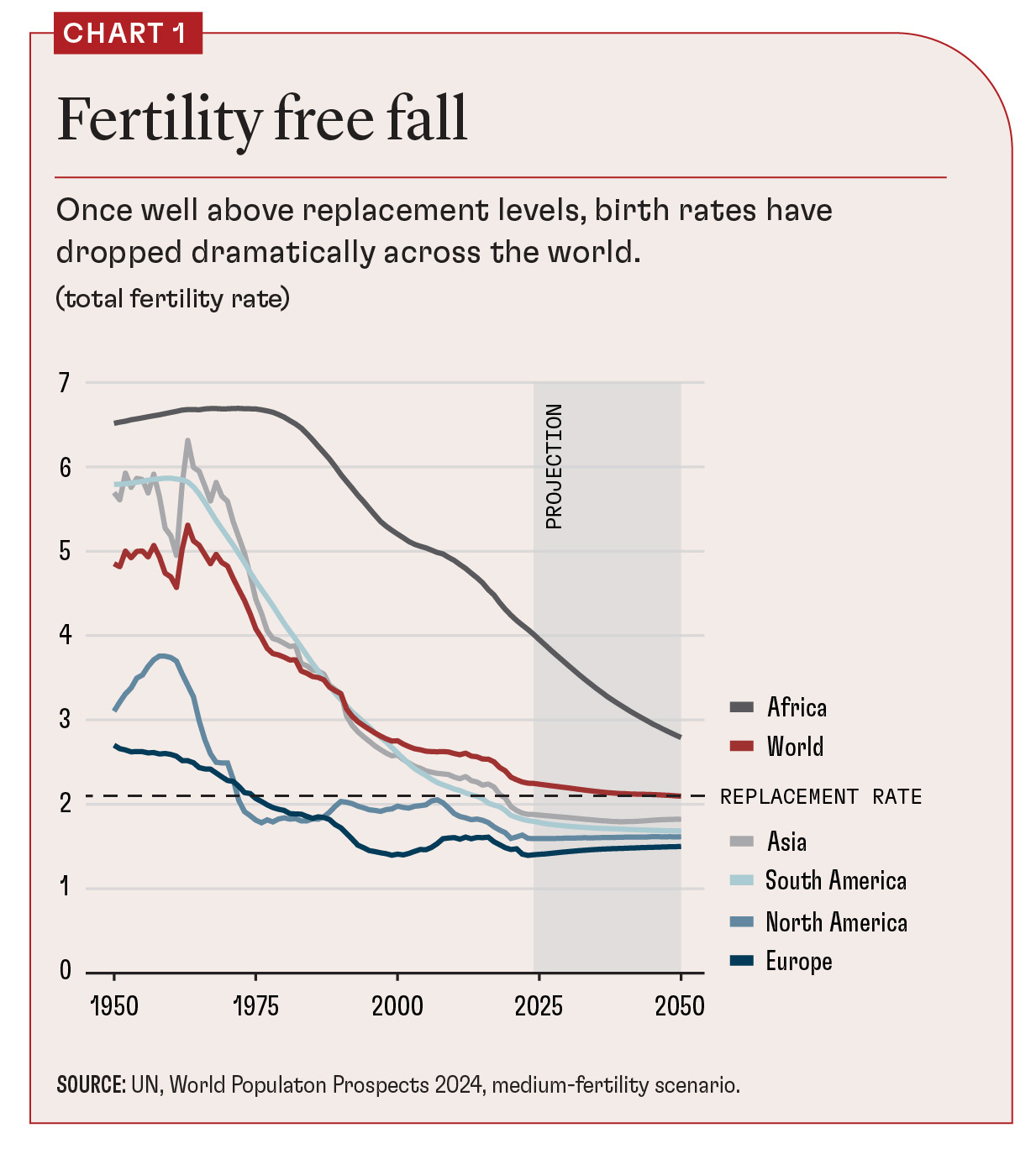

In 1950, the global total fertility rate was 5, meaning that the average woman in the world would have five children during her childbearing years, according to the United Nations Population Division. That was well above the 2.1 benchmark for long-term global population stability. Together with low and falling mortality, this drove global population to more than double over a half century, from 2.5 billion people in 1950 to 6.2 billion in 2000.

A quarter of a century later, the world’s fertility rate stands at 2.24 and is projected to drop below 2.1 around 2050 (see Chart 1). This signals an eventual contraction of the world’s population, which the UN agency expects to top out at 10.3 billion in 2084. Projections of global population in 2050 range from 8.9 billion to more than 10 billion, with fertility rates between 1.61 and 2.59.

These fertility and total population trends hold for much of the world. During 2000–25, fertility rates declined in every UN region of the world and in every World Bank country income group. This will most likely continue over the next 25 years, signaling future global depopulation.

The exceptions to this trend are Africa and a number of low-income countries on other continents where fertility rates are still 4 or higher. As head counts elsewhere dwindle, Africa’s share of global population is likely to increase from 19 percent in 2025 to 26 percent in 2050.

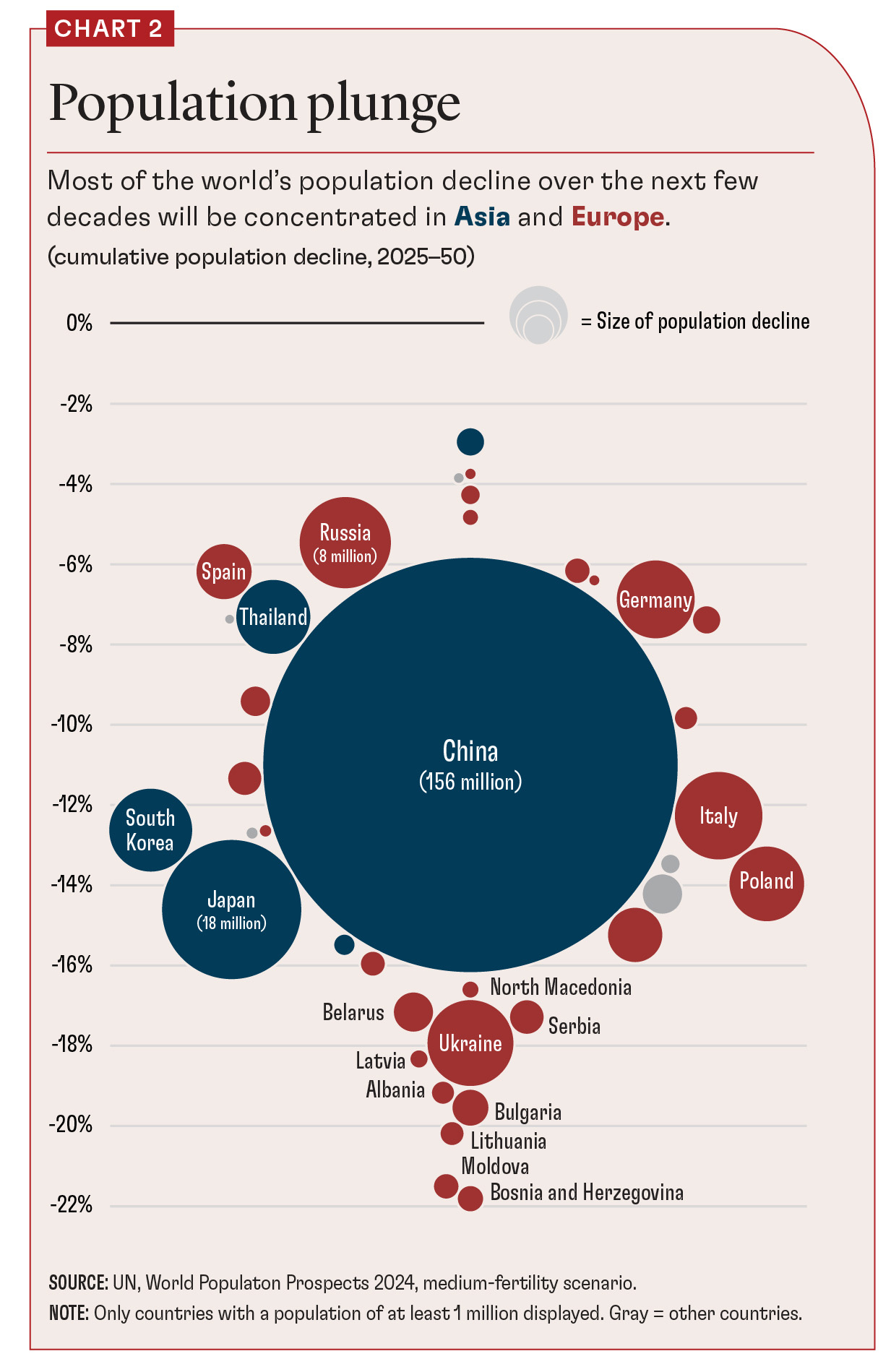

Amid the transition from high to low rates of fertility and mortality, population declines are accelerating. Over the coming quarter century, 38 nations of more than 1 million people each will probably experience population declines, up from 21 in the past 25 years. Population loss in the coming quarter century will be largest in China with a drop of 155.8 million, Japan with 18 million, Russia with 7.9 million, Italy with 7.3 million, Ukraine with 7 million, and South Korea with 6.5 million (Chart 2). In relative terms, average annual rates of population decline will be highest at 0.9 percent in Moldova and in Bosnia and Herzegovina; 0.8 percent in Albania, Bulgaria, and Lithuania; and 0.7 percent in Latvia and Ukraine.

The link between fertility rates of less than 2.1 and depopulation is not ironclad. For example, in 6 of the 21 countries with average fertility rates of less than 2.1 and fewer births than deaths during 2000–25, immigration prevented depopulation.

Recent and projected patterns of population decline generally differ in nature and intensity from those of prominent historical episodes. Those cases of depopulation did not reflect mainly fertility choices but rather mass migrations and Malthusian mortality shocks such as famine, genocide, war, and epidemics. Certainly, the outlook for the populations of Russia and Ukraine would reflect the ongoing three years of warfare after Moscow’s invasion in February 2022.

Previous situations also differed in duration and intensity. During the Black Death of 1346–53, Western Europe lost upward of a quarter of its population to the bubonic plague, corresponding to an average annual rate of population decline of 4 percent or more. By comparison, the population of Moldova—the fastest-depopulating country this century—has fallen by roughly 1 percent annually since 2000.

Low fertility also feeds a related phenomenon: population aging. This amplifies the economic, social, and political challenges facing countries with shrinking populations. Between 2025 and 2050, the share of population ages 65 and older in countries experiencing population declines will almost double from 17.3 percent to 30.9 percent. In countries whose populations are not shrinking, that age group will expand from 3.2 percent to 5.5 percent.

Challenges of low fertility

Low fertility and depopulation can impede economic and social progress. Fewer births and smaller populations naturally mean fewer workers, savers, and spenders, potentially sending an economy into contraction.

A shortage of researchers, inventors, scientists, and other people-based sources of innovative ideas could also hurt economic progress. In a 2022 paper, Stanford economist Charles Jones argues that the implications of low fertility include a drop in the number of new ideas, which could strangle innovation and result in economic stagnation.

Meanwhile, the burgeoning shares of older people that often accompany low fertility and depopulation may also weigh on growth. Younger people tend to drive innovation. Older people work and save less than the young and create significant burdens for prime-age workers through long-term care needs and spending on health and economic security.

A nation’s slow or negative population growth relative to other countries may translate into less military might and political clout on the world stage. For example, some historians attribute France’s 1871 defeat in the Franco-Prussian War to the low fertility and slow rate of population growth that stemmed from early and widespread use of contraception among married couples in France.

Economic opportunities

But there are countervailing forces. Fewer children and smaller populations mean less need for spending on housing and childcare. These resources could be reallocated to research and development, adoption of advanced technologies, and elevation of education quality. Declines in fertility can also stimulate economic growth by driving up rates of labor force participation, especially among women, as well as savings and capital accumulation. This phenomenon followed the end of the post–World War II baby boom and fueled a demographic dividend in many countries, contributing as much as 2–3 percentage points to per capita income growth.

A population’s productive characteristics figure more prominently than its size in defining its capacity for knowledge creation and innovation. The number of healthy and well-educated people represents the human capital that contributes to advances in knowledge and determines technological progress and economic growth. In his book The Journey of Humanity: The Origins of Wealth and Inequality Brown University economist Oded Galor argues that falling fertility and rising education will lead to human capital formation and long-term increases in prosperity.

Population decline may also enhance social welfare if it reduces environmental pressures such as land, air, and water pollution; climate change; deforestation; and the loss of biodiversity.

Adaptation and restructuring

Under what circumstances should policymakers try to address declining fertility, and what measures should they implement?

Those are difficult questions. There is nothing intrinsically wrong with an economy expanding or shrinking along with its population. Regardless, effective fertility policies are notoriously difficult to come by. It’s possible that falling birth rates are a clear expression of societal preferences that we should simply accept. The problems have to do with the side effects, such as declining per capita GDP, stagnating innovation and growth, and the challenges of supporting an aging population.

Those threats have already driven some countries facing declining or low fertility to implement measures to stabilize or increase birth rates. South Korea recently reported a rise in fertility rates for the first time in nine years. China abolished its one-child policy. Japan introduced flexible work arrangements. And several European countries are overhauling their social security systems to ensure sustainability.

Policymakers could deploy a range of family-friendly policies to encourage increased fertility, although more children create economic strains of their own, and an expanded workforce would take two decades to materialize. Such policies could seek to enable a better balance between work and family responsibilities. They might include tax breaks for larger families, extended and more flexible parental leave policies, public or subsidized private childcare, and subsidies for infertility treatment.

Gains in education access and quality could also work to enhance a population’s capacity for innovation. This would enable a society to create more value through work, elevating both individual and societal well-being.

Retirement policy changes—such as raising the age of retirement—have considerable potential to forestall workforce shrinkage by removing disincentives to working longer. Policies related to low fertility and depopulation may be stronger in combination than in isolation. Robust investments in the health and education of youths and prime-age adults may enable people to be sufficiently healthy and well trained to work productively well past the traditional retirement age.

Policymakers must be mindful of the evolving work landscape, particularly the rise of digitalization, robotics, automation, and artificial intelligence. While these tools offer tantalizing potential, their evolution will not only affect the types of jobs available and how they are performed but will also alter the ways that workers interact socially. This too could have significant implications for fertility levels and patterns.

The world is experiencing a dramatic demographic change, from rapid population growth during the past century to depopulation in the current century. The relentless and precipitous fall in fertility is the main driver of this transition, which also involves a historically unprecedented rise in the number of people of advanced age. Policymakers would do well to pay close heed to emerging evidence and global discourse on the economic and social consequences of these demographic shifts. They may not embrace all the consequences, but at least they will be able to point to plausible strategies for addressing them.

Ravi Sadhu, a research assistant at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, also contributed to this article.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.