Older populations need not lead to slumping economic growth and mounting fiscal pressures

The demographic dividend that has supported global economic expansion in recent decades will soon make way for a demographic drag. In advanced economies the share of working-age people is shrinking already. The largest emerging market economies will reach this demographic turning point within the decade, while the most populous low-income countries will get there by 2070. What do falling fertility and rising longevity mean for the world economy?

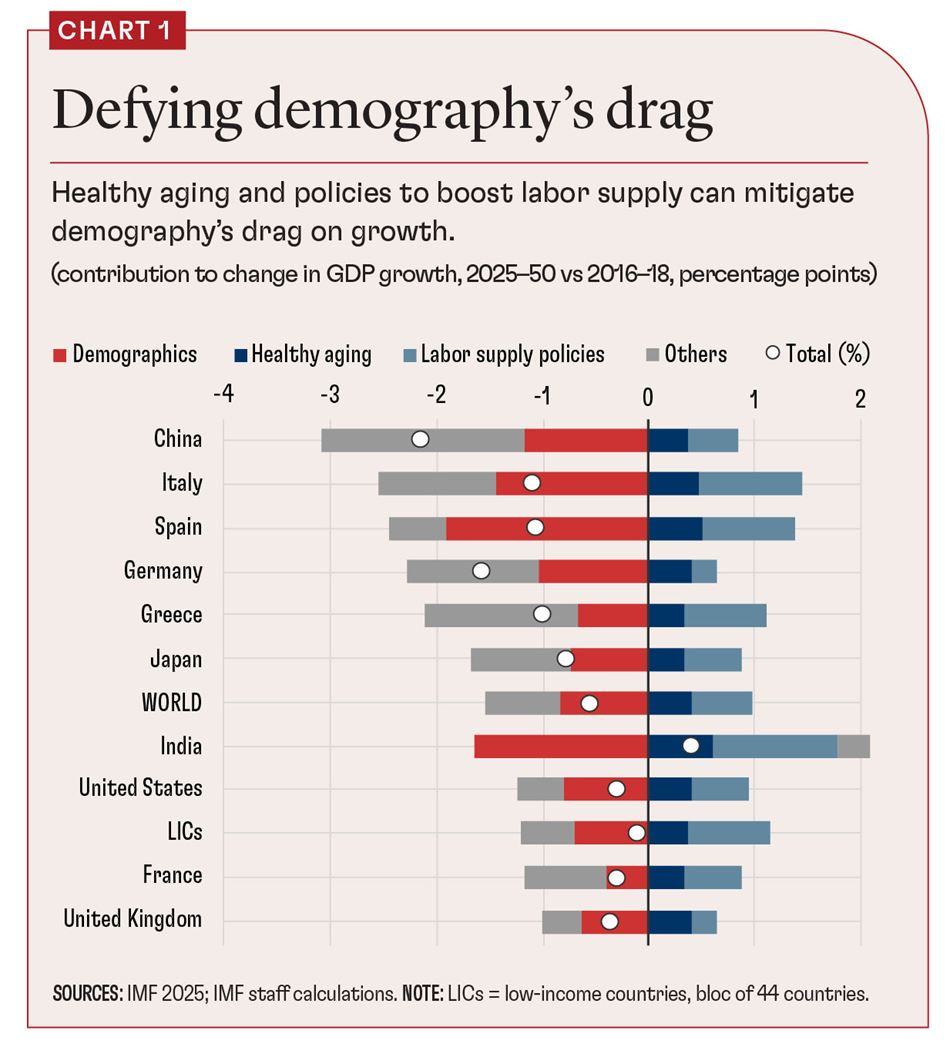

Our recent study with coauthors from the IMF’s Research Department weighs the economic headwinds from older populations against the tailwinds from healthy aging. We show that improved labor market outcomes for people aged 50 and older, thanks to better health, could contribute about 0.4 percentage point annually to global GDP growth in 2025–50 (see dark-blue portions of bars in Chart 1). Global growth would still be about 1.1 percentage points slower than in prepandemic years if governments do nothing, with demography’s drag accounting for almost three-fourths of the decline. But policies to improve people’s human capital and keep them in work as they age could offset a lot of this growth drag.

Healthy aging

We aim to offer a new perspective on the old argument that aging will lead inevitably to slumping economic growth and mounting fiscal pressures. Data on individuals from 41 advanced and emerging market economies reveal that the recent cohorts of older people—those 50 and older—have better physical and cognitive capacities than earlier cohorts of the same age. When it comes to cognitive capacities, the 70s are indeed the new 50s: A person who was 70 in 2022 had the same cognitive health score as a 53-year-old in 2000. Older workers’ physical health—such as grip strength and lung capacity—has also improved.

Better health means better labor market outcomes. Over a decade, the cumulative improvement in cognitive capacities experienced by someone aged 50 or over is associated with an increase of about 20 percentage points in the likelihood of remaining in the labor force. It’s also associated with an additional six hours worked per week and a 30 percent increase in earnings. All this could mitigate aging’s drag on growth.

Economic impact

Demography’s economic impact is multifaceted. First, variations in demographic drivers—fertility, mortality, and migration—impact both population growth rates and age structures. This has a direct bearing on growth through a declining share of the working-age population. It may also strain public finances if longevity means more years in retirement. The growth impact may be compounded over time as slower population growth—or shrinking populations—leads to fewer new ideas and inventions that power long-term productivity growth.

Second, people’s savings are influenced by the span of their working life relative to years in retirement. A longer retirement incentivizes workers to save more to maintain a decent living standard in old age. This increases aggregate savings. A shrinking workforce also means lower investment needs. By influencing savings supply and investment demand, aging is an important driver of interest rates.

Third, the different paces of aging across economies creates opportunities for efficiency gains from cross-border resource reallocation: Capital may flow from old, high-saving economies to younger, capital-scarce economies. There may be incentives for labor to migrate from younger, labor-abundant economies to older economies facing labor shortages.

Using a framework that takes all these channels into account, our analysis indicates that global growth will slow in the future—despite the positive effects of healthy aging on the labor supply and productivity of older workers. Some advanced economies with relatively older populations (such as Japan) are likely to see their economies shrink. Others (notably Canada and the United States) are expected to continue to grow during this century, albeit at a slower pace.

Among emerging market and developing economies, China will see a particularly sharp decline in GDP growth. Driven by acutely adverse demographics and the end of rapid catch-up to the world’s productivity frontier, China’s growth will slow by about 2.7 percentage points relative to 2016–18. We expect India to see a milder growth decline, of about 0.7 percentage point in 2025–50, as its near-term demographics remain favorable. But India and low-income developing countries are set to experience a sharper growth slowdown from 2050 onward.

Policies that help

These projections are not set in stone. In many countries, a significant fraction of workers leaves the labor force after 50, well before statutory retirement age. Health improvements in recent decades indicate that health policies can enhance the human capital of older workers, leading to longer and more productive working lives. Policies that reduce the sizable disparities in health outcomes across socioeconomic groups and countries could reinforce this trend. Other policies to boost labor supply, notably among women, and adjusting incentives to foster longer careers, would also help.

Will it make a difference? Consider the following scenario. First, suppose governments implement additional public health measures that narrow cross-country gaps in the functional capacity of older individuals by about one-fourth over the next four decades. Second, suppose these health measures are complemented by changes to retirement plans, training programs, and more flexible work conditions that incentivize a gradual rise in the effective retirement age in line with improvements in life expectancy. Finally, suppose that policies narrow gender gaps in labor force participation by three-fourths by 2040.

Our simulations indicate that these policies could boost global annual output growth by about 0.6 percentage point over the next 25 years (see light-blue portions of bars in Chart 1). This offsets almost three-fourths of the estimated demographic drag during that period. The growth dividends vary across countries. India, for instance, could see a strong boost to growth given large existing gender gaps in labor force participation. European economies where the effective retirement age is low relative to life expectancy (such as Greece, Italy, and Spain) would benefit from incentivizing longer working lives.

For the majority of countries in our study, the improvements in health and labor supply assumed in this exercise are comparable to trends observed over the past two decades. They are, in other words, within reach.

This article draws on Chapter 2 of the IMF’s April 2025 World Economic Outlook, by Bertrand Gruss, Eric Huang, Andresa Lagerborg, Diaa Noureldin, and Galip Kemal Ozhan, with support from Pedro de Barros Gagliardi and Ziyan Han.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.