For 60 years, the magazine has been a window into the IMF and the evolving global economy

The Beatles are all the rage. The US Congress passes the Civil Rights Act. Nelson Mandela is condemned to life in prison in South Africa. Audrey Hepburn stars in My Fair Lady. And in Washington, on a quiet corner of 19th Street, NW, a magazine is born.

The debut of Finance & Development (F&D) in June 1964 may not have been as momentous as other events of that year, but it marked the opening of a unique window for the public to peer into the workings—and thinking—of the IMF and the World Bank. Over time, it would also allow the Bank and Fund to see how outsiders view a variety of economic and financial topics critical to their work.

When IMF Deputy Managing Director Frank A. Southard Jr. proposed a “less technical periodical” to reach government officials, bankers, journalists, and students he envisioned a Fund-only product (as it later became, when the World Bank dropped out in the 1990s). However, he welcomed World Bank President George Woods’s suggestion for a joint publication, which opened the magazine to a broader range of topics and widened its appeal to readers in the developing world.

The beginnings

The early issues of The Fund and Bank Review: Finance & Development set the stage for the rest of the decade, its mission firmly anchored in information for the general reader about the World Bank and the IMF. There were articles on the origins of the two institutions, their financial structures, and operations. Shorter pieces demystified Fund jargon—such as Stand-By Arrangements, balance of payments deficits, and multiple currency practices—and detailed both institutions’ financial transactions and activities.

F&D was not produced in a vacuum. During the 1960s, the developing world, in the throes of decolonization, aspired to catch up to wealthier countries. At the Bank, following the development logic of the time—industrialization leads to growth; growth helps the poor—the emphasis was on project lending for infrastructure and industry. F&D carried numerous articles profiling Bank-funded projects and explaining the practicalities of lending for development.

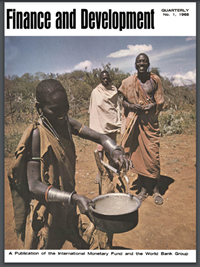

Since the first illustrated cover, in March 1968, showcasing Kenyan villagers at a new World Bank–financed water tap, F&D has portrayed successful projects as symbols of modernity and prosperity. The September 1968 cover and its accompanying article highlighted how new irrigation dams were turning a Mexican desert into fertile farmland. Visitors to the 1968 Olympic Games, it promised, could thus expect to dine on produce “grown by the farmers of this newly prosperous area.” Another piece described the Western Highway in Honduras—financed by the International Development Association’s first loan—as “the hypodermic needle by which the vaccine of modern life is being injected into the countryside.”

Yet by the end of the decade, the paradigm of industrialization-driven development was being challenged. In his 1968 book Asian Drama: An Inquiry into the Poverty of Nations, Nobel Laureate Gunnar Myrdal asserted that “development is not a mechanical process of adding to capital stock, human skills, technological knowledge and artifices but a matter of institutional change, of attitudes and behavior patterns, of all those intangible elements that distinguish a human society from a field of particles or a colony of ants.” To the World Bank’s economists this was heresy, and in June 1969, F&D published a lengthy rejoinder—not so much questioning Myrdal’s thesis as critiquing his lack of practical solutions.

By the next year, however, Bank President Robert S. McNamara was calling for development indicators that “go beyond the measure of growth in total output and provide practical yardsticks of change in the other economic, social, and moral dimensions of the modernizing process.”

This was also the heyday of the Bretton Woods system: a 1966 article proudly proclaimed 20 years of fixed exchange rates. But the system was already under strain. Several articles from the late 1960s discussed the intertwined problems of the US balance of payments and global liquidity until the IMF introduced an artificial reserve asset, special drawing rights (SDRs), featured prominently on the December 1969 cover. For developing economies, which had hoped for a link between SDR allocations and development finance, the IMF could trot out only its standard policy prescription—reiterated in several F&D articles—that monetary and exchange rate stability were the sine qua non of economic development.

As the 1960s neared their end, so did the Bretton Woods system, which would collapse only a few years later. But F&D was a success: between 1964 and 1968, circulation in its three original languages—English, French, and Spanish—rose from 20,000 to 85,000. The magazine had established itself as a serious medium for communicating the work of the Bank and the Fund. Tentatively at first, but with increasing confidence, its editors began playing with color and graphics by including larger and more frequent photographs, maps, charts, and illustrations.

The turbulent 1970s

The 1970s was a stormy decade—punctuated by the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, massive oil price shocks, and international terrorism. But it was also a time of experimentation. The Second Amendment to the IMF’s Articles of Agreement, in 1978, allowed members to choose their exchange rate regime—fixed or floating. More significantly, as the Fund’s economic counsellor explained in F&D’s June 1976 issue, it represented a revolution in thinking about the stability of the international monetary system.

Under Bretton Woods, stability was premised on countries maintaining fixed exchange rates against the dollar. After the Second Amendment, countries would direct their monetary and fiscal policies toward domestic stability, with exchange rate stability emerging from good economic policies, regardless of choice of exchange rate regime. Future IMF surveillance, therefore, would expand to include not only external stability but domestic policies and stability as well. This would open the door to an expanding scope of Fund surveillance, which today covers such diverse topics as gender equality, governance, and climate change.

The road to the Second Amendment was bumpy, and F&D strove to inform readers of efforts to reform the international monetary system, debates on fixed versus floating exchange rates, dislocations caused by oil price shocks, and the practicalities of implementing the amended Articles. Developing economies again clamored for an SDR-development link and were again rebuffed. Instead, the IMF offered the Extended Fund Facility, which provided for longer arrangements (and repayment periods) than the traditional Stand-By Arrangements, and made its first foray into concessional lending through a new trust fund (given prominence in F&D’s December 1976 issue). The magnitude of the oil price shock meant that to meet its members’ demands, the IMF had to supplement its quota resources with the funds it borrowed from oil exporters—in effect, recycling petrodollars. In June 1975, F&D added an Arabic language edition.

The World Bank was also undergoing a revolution. F&D reported extensively on the 1973 Nairobi Annual Meetings, at which McNamara stressed the need to tackle absolute poverty directly. The Bank (and the broader development community) was beginning to recognize that gross national product growth “often does not filter down.” But the answer was not handouts: McNamara figured that the only durable solution was raising the productivity of the (mostly rural) poor. F&D explored the types of World Bank projects, writing that they were no longer “the monolithic, engineering projects of the late 1940s and early 1950s” but multifaceted, complex, sophisticated operations. Throughout the 1970s, F&D showcased Bank initiatives to help the small farmer access credit, seeds, and fertilizer, complemented by expanded provision of education, health care, irrigation, and public transportation.

Back at the editorial offices of F&D, the editors experimented with funkier fonts and formats, as seen in the March 1973 issue. More substantively, they began exploring novel topics. A 1969 F&D article first spotlighted weather as “a key variable in economic development to which economic and financial institutions have so far given little attention.” In December 1971, Margaret de Vries—the Fund’s pioneering female division chief—wrote a compelling piece on women’s role in economic development. The magazine also highlighted the benefits of guest workers in Europe, noting the advantages for both migrants and host countries, even as the latter were beginning to grapple with immigration’s social and political impact.

1980s: The lost decade

In advanced economies, the Margaret Thatcher–Ronald Reagan years are remembered for Wall Street’s excesses. But for much of the developing world, the 1980s was a lost decade.

At the end of the 1970s, the Federal Reserve pulled hard on its monetary reins to curb high US inflation. Soaring global interest rates brought the easy-money lending of the previous decade to an abrupt end and sent indebted developing economies into a tailspin. At the IMF, the new watchword was “conditionality.” Not only was meeting certain policy conditions the key to unlocking Fund resources—as F&D’s March 1981 cover made clear—it was also essential to successful adjustment, so that fresh lending did not simply mean piling on more debt.

At the World Bank, there was increasing recognition that investment projects, regardless of their internal rate of return, could never thrive if the macroeconomic environment was in disarray. The answer was a new type of lending: structural adjustment loans providing budget support for economic reforms. Both Bank and Fund programs stressed the need to restore internal and external balance—on the demand side, by cutting budget deficits and imposing monetary discipline, and on the supply side, through devaluation, privatization, and liberalization.

Developing economies resented this new direction. Critics decried the harsh measures and strict conditionality, which they claimed unnecessarily exacerbated economic hardship, especially for the poor. F&D played a crucial role here in explaining that timely and orderly adjustment, despite short-term pain, would lead to longer-term gains, including higher growth, improved living standards, and better income distribution.

Other articles advocated market-oriented reforms, especially trade liberalization over protectionism and import substitution. The East Asian economies were showcased for their successful adjustment and lauded for their trade openness, which—F&D authors claimed—had resulted in faster recovery and growth (although, in reality, these countries were also distinguished by extensive government intervention). F&D also began to take notice of China, which had just embarked on market-oriented reforms; in June 1983, it began to publish in Chinese.

As the debt crisis dragged on and adjustment fatigue set in, it became increasingly clear that aggressive adjustment had a disproportionate impact on the poor. To be politically sustainable, programs would need to do more to protect the most vulnerable. Through the pages of F&D, readers could trace the evolution of the international community’s debt strategy: an initial emphasis on adjustment; the 1985 Baker Plan premised on countries “growing out” of their indebtedness; and finally acceptance, under the 1989 Brady Plan and Paris Club Toronto terms, that only debt relief—from both market and official bilateral creditors—could resolve the crisis.

F&D also covered the World Bank’s growing involvement in environmental concerns, which began with the establishment of a small unit in 1970 and received further impetus during Barber Conable’s presidency (1986–91). Against a backdrop of public criticism of the environmental impact of certain World Bank projects, F&D began publishing articles on the Bank’s shift toward viewing environmental preservation as part of sustainable development.

F&D opened up to external authors, starting with Nicholas Kaldor in June 1983. Guest articles were clearly identified, lest there be any confusion that they represented institutional views, and Kaldor’s piece—questioning IMF orthodoxy about currency devaluations—was published alongside a rejoinder by F&D’s editor-in-chief. Nonetheless, these articles helped introduce an element of debate, paving the way for F&D to become less a vehicle for disseminating Bank and Fund views and more of a platform for discourse.

1990s: Transition

With cover art reminiscent of 1930s Soviet propaganda posters, F&D’s March 1990 issue explored the biggest story of the decade: the fall of communism and seeming triumph of liberalism. The Bank and the Fund—together with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the nascent European Bank for Reconstruction and Development—were already at work on A Study of the Soviet Economy, which concluded (as a 1991 F&D article explained) that the required reforms were interconnected: gradualism would not work; “shock-therapy” was needed. Subsequent F&D issues explored various aspects of the transition—fiscal consolidation, monetary reform, privatization, reorientation of industries, corporate governance—occasionally giving voice to those who called for “less shock, more therapy.”

Outside the transition economies, developing economies and emerging markets were also transforming, accepting most of the ideas and broader impetus toward liberalization—while rejecting the rhetoric—of the so-called Washington Consensus. However, as the Bank’s East Asian Miracle report—referenced on the cover of F&D’s March 1994 issue—acknowledged, state intervention could be constructive, provided there was “good governance.”

Optimism about unbridled market capitalism was tested by the 1990s emerging market crises. As part of liberalization efforts, many emerging market economies had dismantled their capital controls, inviting large inflows. Before long, however, the 1994 devaluation by Mexico—followed shortly by Thailand, Korea, Indonesia, Russia, Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, and Türkiye—demonstrated the devastating consequences of sharp reversals of capital flows. While the roots of individual capital account crises were country-specific, in each case, balance sheet mismatches—such as loans denominated in dollars that had to be paid off from assets that generated local currency—left economies vulnerable to destabilizing events, whether domestic or external, economic or political.

Having unveiled for the first time the dark side of financial globalization, the 1997–98 Asian Crisis and its lessons ushered in numerous IMF reforms, detailed in the June 1998 F&D. Emerging market crises more generally spurred various initiatives (such as standards and codes, the Financial Sector Assessment Program, and early-warning systems) to strengthen the international financial architecture.

Transition economies and emerging markets may have grabbed F&D headlines, but low-income countries were no less important. The IMF had long maintained that macroeconomic stability was necessary for growth, and growth for poverty reduction. The intellectual leap—articulated in F&D’s How We Can Help the Poor (December 2000)—was recognizing that “necessary” did not imply “sufficient”: poverty reduction should be a goal of its own, alongside growth. Accordingly, the Fund’s marquee Enhanced Structural Adjustment Facility became the Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility. Government officials and civil society would now craft their own poverty reduction strategies in a participatory process, enhancing program ownership. In recognition of countries’ reform efforts, the Fund and Bank also agreed to debt relief under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative (supplemented in the mid-2000s by the even more ambitious Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative).

F&D itself changed profoundly. Soon after James Wolfensohn arrived at the World Bank in 1995, the Bank withdrew from the F&D partnership. The Fund, however, recognized F&D’s value and agreed to finance it on its own. Despite this shift, F&D’s 110,000+ subscribers would see little change in the coverage of topics. More noticeable was the new emphasis on visual communication, with arresting covers and four-color printing, as well as more external—and even critical—perspectives. In March 1996, F&D also began supplementing its print editions with digital content.

Into the new millennium

Over the next few years, F&D emerged in its modern format. With the advent of greater transparency and publication of IMF documents, there was less need for F&D to act as its mouthpiece. Instead, the magazine became a platform where topics of importance to the Fund could be debated by the world’s leading experts. The issues also became more thematic.

Also in the early 2000s, emerging markets arrived on the world stage. Asian economies led the pack: the crisis countries had recovered, and the sleeping giants—China and India—had awakened. But it was not only Asia: Latin America’s and even Africa’s performance and prospects were much improved. The major emerging markets, now accounting for a growing share of world output but still holding only a minority of IMF quotas, started demanding a larger seat at the table.

But East Asia’s export-led boom was not without drawbacks. As emerging markets—especially China, which became a manufacturing and exporting powerhouse after its 2001 World Trade Organization accession—made inroads into the advanced economies’ industrial sectors, they sparked a protectionist backlash. Even as the Doha Round of trade liberalization stalled, the Bretton Woods institutions continued to champion trade and globalization: all countries could improve their lot by Trading Up (F&D, September 2002). For poorer countries, the prescription was still that trade liberalization—as much as increased aid—held the key to boosting growth and eradicating poverty. Meanwhile, advanced economy workers’ worries about job losses were dismissed on the grounds that trade creates enough winners that they could compensate losers.

At a macroeconomic level, Asia’s rise was reflected in “global imbalances”—principally, China’s surplus and the US deficit, causing trade and exchange rate frictions between them. The systemic concern—which prompted the IMF in 2006 to convene its first Multilateral Consultation—was that the buildup of US liabilities could reach a tipping point, and investors might lose confidence and dump their dollars, precipitating a global crisis. In fact, the imbalances were but a symptom: the roots of the 2008 crisis were deeper.

By the mid-2000s, the world economy was booming, but only as a result of a triple bubble:

- Excess saving and production in Asia could be sustained only by the huge current account deficit of the United States, which became the consumer of last resort.

- Stagnating real wages and a declining share of labor income in the US—including as a result of manufacturing jobs moving to emerging markets—meant that middle-class consumption could be sustained only by ever-increasing amounts of consumer credit (often in the form of equity withdrawals from rising house prices).

- In the euro area, a similar bubble sustained northern European surpluses and southern European deficits.

These factors were enabled—and exacerbated—by financial sector excesses that flourished under poor regulation. While F&D picked up on some of these elements, it failed, along with most other observers, to connect the dots and recognize that, as these bubbles burst, the world economy would suffer its worst crisis since the Great Depression.

Crisis and recovery

Even before the bankruptcy of US investment bank Lehman Brothers sparked global financial panic, F&D’s June 2008 issue pointed to opaque, complex mortgage-backed securities, coupled with excessive leverage and regulatory failures, as the source of the financial problems in the United States. Lehman’s failure in September and the spread of the ensuing full-blown crisis to the rest of the world, received ample coverage in F&D’s December 2008 issue.

Over the following year, the magazine detailed the IMF’s crisis response: overhauling its lending tool kit to make it more flexible and responsive to countries’ needs; improving surveillance to better anticipate crises and take account of spillovers; and, together with the Financial Stability Board, strengthening its oversight of the global financial system. The Fund also provided additional support to low-income countries and revived SDRs—its first allocation since the 1970s—to boost the global economy with an immediate injection of unconditional liquidity.

As the crisis broke, Managing Director Dominique Strauss-Kahn famously called for emergency fiscal stimulus. Countries heeded the call, with Asia leading the way. China’s massive fiscal expansion in particular served as a locomotive for the rest of the global economy. Major central banks pumped emergency liquidity into their markets, established cross-border swap lines, and engaged in quantitative easing. These actions were essential to avoiding an implosion of the world economy, though they also resulted in unwanted surges of capital flows to emerging markets.

By December 2009, the worst of the storm had passed. But the scars of the crisis—structural unemployment, income inequality, protectionism, and anti-globalization sentiment—ran deep. These now became the focus of F&D. In Jobs on the Line—whose cover drew inspiration from Diego Rivera’s 1932 homage to the American worker—F&D explored how migration, outsourcing, technology, and trade were affecting job prospects. It pointed to a basic dilemma for policymakers: greater openness to migrants, trade, and technology brought economic benefits but also political costs, as the middle class felt threatened. While retooling and further education were part of the answer, F&D said, “for displaced workers near the end of their working lives, redistribution may be a more practical solution than acquisition of new skills.”

The September 2011 F&D explored a related issue: public resentment of growing income inequality in advanced economies, in part because of perceptions that banks had been bailed out on the backs of workers. The risk was that people would “no longer support open trade and free markets if they feel that they are losing out while a small group of winners is getting richer and richer.”

A fraught, fragmented world

By 2016, after the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union, fragmentation was no longer a risk but a reality. Just as the global recovery seemed to have reached an inflection point, it faced setbacks from rising nationalism, protectionism, and populism. Earlier doubts about globalization now turned into open trade wars and xenophobia. Movements like Occupy Wall Street morphed into calls for antiestablishment politicians and wholesale rejection of expertise. Not only had the consensus and cooperative spirit of the early days of the crisis melted away, it had turned into a willful desire to break agreements, reconsider alliances, and retreat from multilateralism.

F&D sought to diagnose this new reality. The December 2016 issue—featuring a stolid blue-collar worker on its cover—explored the hollowing out of the American middle class and the root causes of disaffection gripping electorates in advanced economies. While globalization seemed like the obvious culprit, the March 2017 issue evaluated a different hypothesis: secular stagnation. The key question—as F&D posed it—was whether advanced economies should resign themselves to anemic growth or whether policies could revive productivity. Summing up the mood of the era, the December 2018 F&D, Age of Insecurity, asked what remains of the social contract in the 21st century, when the elderly worry that they will outlive their pensions while millennials fret that they will never earn theirs in the first place.

The COVID-19 pandemic dealt the next blow. The IMF pulled out its crisis playbook, swiftly providing emergency financing to an unprecedented number of countries. It also issued a record number of SDRs, with the 2022 Resilience and Sustainability Trust finally providing an ingenious—albeit partial—workaround in response to developing economies’ long-standing gripe that allocations are proportional to quota rather than countries’ structural financing needs. But what should have brought the world together instead amplified divisions, culminating in “vaccine protectionism.”

Beyond assessing the pandemic’s immediate impact, F&D pondered its longer-term implications for economic opportunity, inequality, technology, health, and the praxis of fiscal policy. It also urged its readers to see the pandemic as an opportunity for healing the fractures and building back a better world (September 2020 F&D).

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine delivered the next set of shocks: refugees, supply-chain disruptions, food and energy shortages, high inflation, and unstable financial markets. Against the backdrop of rising US-China rivalry and the world’s dangerous drift into distinct economic blocs, the war has reinforced the sense that countries must take sides. To help its readers make sense of this landscape, F&D explored its impact on policymaking, the global economy, energy insecurity, and disintegration of global trade.

What next for the Fund? Forged in the crucible of war and created to foster multilateralism and international cooperation, its mission is more vital than ever. But to fulfill it effectively in an increasingly complex and shock-prone world, its staff need to look up from their spreadsheets and study issues outside their traditional domain. F&D is doing its part, delving into a panoply of topics ranging from health, demographics, and inequality to digital currency and artificial intelligence. Its most recent issue takes stock of what it all means for the economics discipline itself.

Ahead of its time

F&D was originally intended to keep readers abreast of World Bank and IMF developments; it has done so admirably. But it has also evolved into a vital forum for debate on critical economic issues. And on some topics—the environment, the role of women, the rise of China—F&D has been ahead of the curve.

In June 2019, the magazine carried a fictional account of John Maynard Keynes returning to visit the Fund on its 75th anniversary, where he marvels that—despite myriad changes—the institution remains true to its purpose of serving its membership. Over the past 60 years, F&D, too, has witnessed—and experienced—numerous transformations while staying true to its purpose of engaging, educating, and entertaining its readership.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.