Published on April 7, 2022

The Future of Inflation Part I: In the first installment of our three-part series on the future of inflation, we ask whether high inflation will persist and how central banks will respond

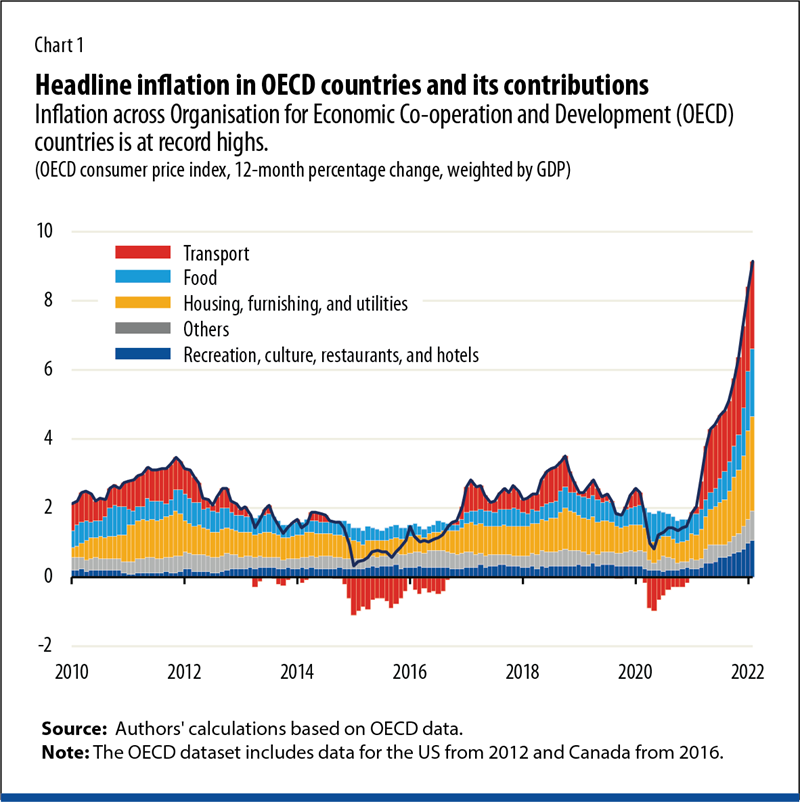

The recent increase in inflation worldwide took many by surprise. As of early 2022, both headline inflation (price of all goods and services) and core inflation (excluding food and energy) were significantly above target in most advanced economies and several emerging markets (Chart 1). Standard economic theory states that inflation will get out of control under a prolonged mix of certain monetary and fiscal policies, but whether inflation will persist toward that end warrants further examination. The answer depends both on the distribution of shocks to the economy and how central banks (and finance ministries) react.

Inflation persistence

Why inflation is high and whether it will persist is a topic of active debate. We see five key drivers of the current inflation surge, with implications for this debate.

First, supply chain bottlenecks: The pandemic had two separate effects on global supply chains. In the early phase, lockdowns and mobility restrictions led to severe disruptions in various supply chains, causing short-term supply shortages. Many of these disruptions have eased, although the recent surge in Omicron has renewed pressure on some supply chains. In the later stage of the pandemic, however, various supply chain bottlenecks have emerged as a result of strong overall demand from the economic recovery, the sharp increase in relative demand for durable goods, and hoarding and panic buying. According to a recent assessment by Rees and Rungcharoenkitkul (2021), the most severe bottlenecks affect raw materials, intermediate manufactured goods, and freight transport. Will these persist? One measure of the state of global supply chains is how long it takes to ship goods by sea. The two biggest trade lanes carry goods from Asia to North America and from Asia to Europe. The Flexport Ocean Timeliness Indicator captures timing for each of these routes. As of the end of February 2022, measures for both remain close to all-time highs, suggesting significant ongoing pressure that may persist for at least a few more months.

Second, a shift in demand toward goods and away from services: The pandemic brought about an initial significant shift in what consumers buy; spending on goods rose dramatically. Consequently, much of the rise in inflation in the near term reflected inflation in durable goods (including used cars), while service inflation increased only moderately. Such shifts may persist only during the active phase of the pandemic, but at least part of the shift in demand toward goods and away from services may persist given how the pandemic has reshaped society. As Emi Nakamura (2022) put it in a recent interview with Noah Smith, “to the extent that people shift to a lot more work from home (and less people are working at all) this could make some of the changes in demand patterns quite persistent.” While the shift toward durable goods occurred globally, the impact may have been greater in some countries (for example, thanks to the boom in used cars in the United States).

Third, aggregate stimulus and post-pandemic recovery: About $16.9 trillion in fiscal measures was announced globally to fight the pandemic, with relatively larger support in advanced economies. In the United States alone, a $1.9 trillion fiscal stimulus (the American Rescue Plan) was introduced. A warning that the large fiscal stimulus, combined with easy monetary conditions, would lead to high and persistent inflation came from a group known as ”Team Persistent.” The name can be traced to inflation warnings in early 2021 from Larry Summers and Olivier Blanchard, among others. Observers who came to be known as ”Team Transitory” opposed this view and argued that inflationary consequences of the government stimulus would likely be temporary or mild. By the end of the year, the evidence had shifted in favor of Team Persistent across several countries. Households were running down the savings they had accumulated earlier in the pandemic (including from the stimulus and transfers), which led to a surge in aggregate demand and a stronger-than-expected economic recovery. Whether the strong aggregate demand will persist is ultimately a question of how the central bank responds. This remains a hotly debated question, which we return to in a later section.

Fourth, a shock to labor supply: Labor market disruptions from the pandemic continue even two years after it began. Labor supply participation remains below pre-pandemic levels in several countries. Among advanced economies, the impact has been relatively larger in the United States, where participation is about 1.5 percent lower than before the pandemic (about 4 million fewer workers). Will this shock persist? Views differ. In a recent paper, Alex Domash and Larry Summers (2022) examine different labor market indicators and argue that “even under optimistic COVID-19 outcomes, the majority of the employment shortfall will likely persist moving forward” and “contribute significantly to inflationary pressure in the United States for some time to come” due to higher wages pushing up costs.

Fifth, supply shocks to energy and food because of the Russian invasion of Ukraine: The February 24, 2022, invasion has led to rising energy and food prices, which will inevitably mean higher inflation globally. Both Russia and Ukraine are exporters of major commodities, and the disruptions from the war and sanctions have caused global prices to soar, especially for oil and natural gas. Food prices have also jumped. Wheat prices are at record highs—Ukraine and Russia account for 30 percent of global wheat exports. These effects will lead inflation to persist longer than previously expected. The impact will likely be bigger for low-income countries and emerging markets, where food and energy are a larger share of consumption (as high as 50 percent in Africa).

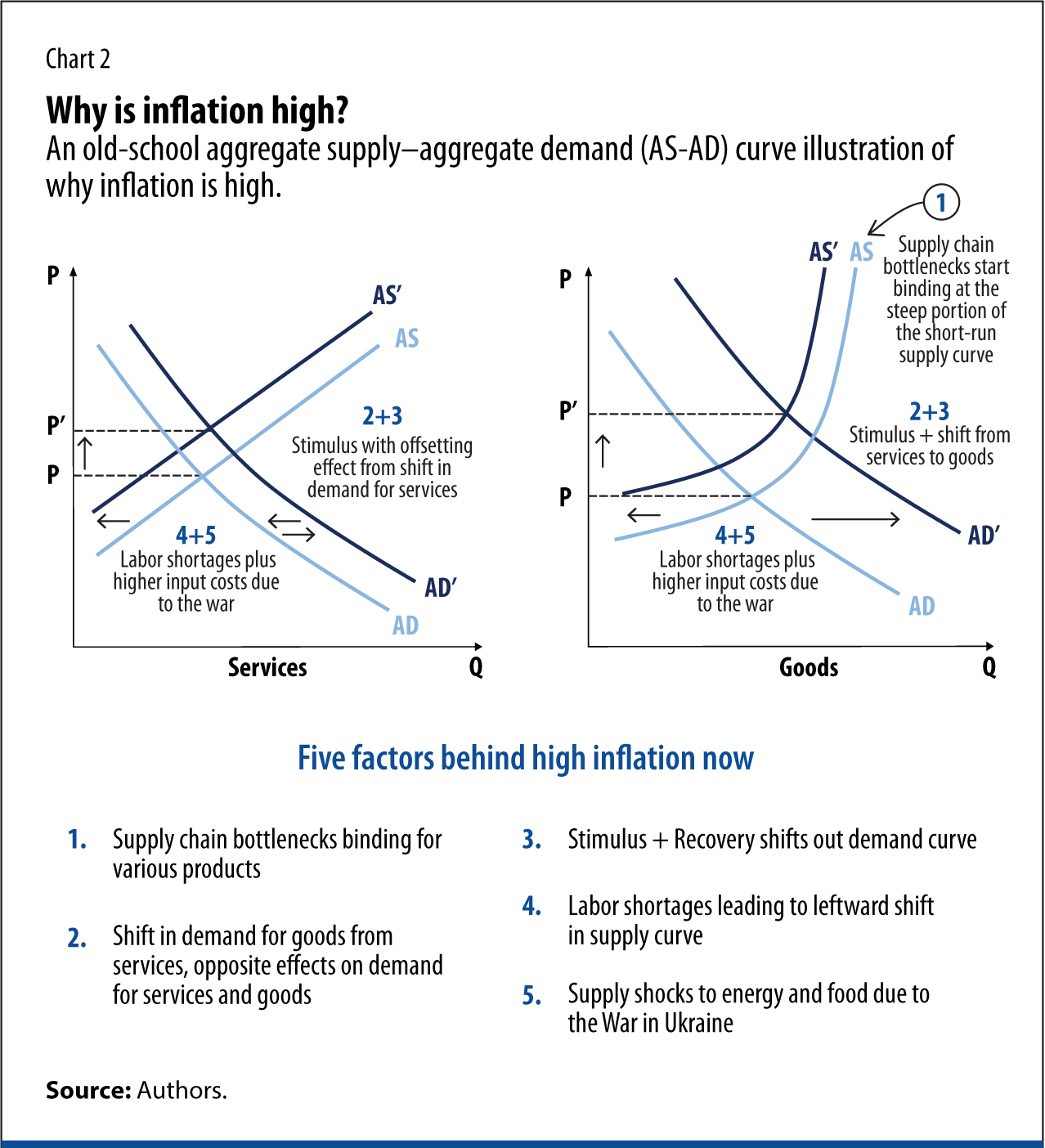

We summarize these five effects using textbook aggregate supply and demand (AS-AD) curves (Chart 2). The AS-AD framework is old-school but still useful for analyzing the current situation. The effects of the four drivers of inflation are depicted separately for the goods markets and the services markets. First, supply chain bottlenecks start binding as the economy moves along the steep portion of the short-term supply curve in the goods market. Second, the shift in preferences for goods leads to a rightward shift in the AD curve in the goods market and a leftward shift of the AD curve in the services market. Third, the strong fiscal stimulus leads to a rightward shift in the AD curve in both markets. Fourth, the shock to labor supply and commodity and food prices leads to a leftward shift in the AS curve in both markets as input costs rise. Consequently, there was an initial modest increase in prices for services, but a larger increase for goods (which may be reversing now).

Economists continue to read the tea leaves to predict how inflation will evolve. While there are important cross-country differences, inflation has risen almost everywhere in the world. The key uncertainties now are about the duration of labor market tightness and supply chain bottlenecks, and about how central banks will respond to high inflation.

Central bank responses

How will central banks respond to inflation? If the past is any indication of the future, it is helpful to first examine how central banks acted before the pandemic. Until the late 1970s, central banks were more tolerant of inflation. But the dramatic disinflation in the United Kingdom under Margaret Thatcher (before Bank of England operational independence) and by the Federal Reserve under Paul Volcker brought about a revolution in how central banks respond to inflation. Soon after, many other central banks followed these two salient examples, bringing about a decline in inflation in much of the world by the mid-1980s. This required significant institutional reform toward central bank independence and the ability of some central banks to navigate political headwinds and successfully establish de facto independence.

It is common for central banks to copy successful strategies of other central banks, although this often requires institutional reforms. High inflation made it more likely that central banks would imitate strategies that seemed successful at reducing inflation. In addition, various reforms made it possible to staff central banks with economists and others trained in the causes of the Great Inflation of the 1970s and ways to bring inflation back down, which plausibly also played a role in this central banking revolution.

Our analysis shows that, of all the countries that brought inflation under control, very few later experienced a surge in out-of-control persistent inflation. That is, very few countries have fallen off the wagon after sobering up from high inflation (or after staying sober into the early 1990s). This was also supported by institutional reforms that empowered central banks to withstand political pressure to generate growth by cranking up inflation at opportune moments.

In saying this, we use specific definitions for some of our empirical exercises. “Having brought inflation under control” is defined as a three-year stretch of quarterly inflation remaining below 4 percent since 1990. The first time a central bank achieves this, we call it their Blue Chip Month. Members of Alcoholics Anonymous and other 12-step groups receive a sobriety coin or “chip” marking how long they have remained sober. The chips are meant to motivate holders to stay the course. Similarly, the Blue Chip Month marks three years of inflation sobriety for central banks.

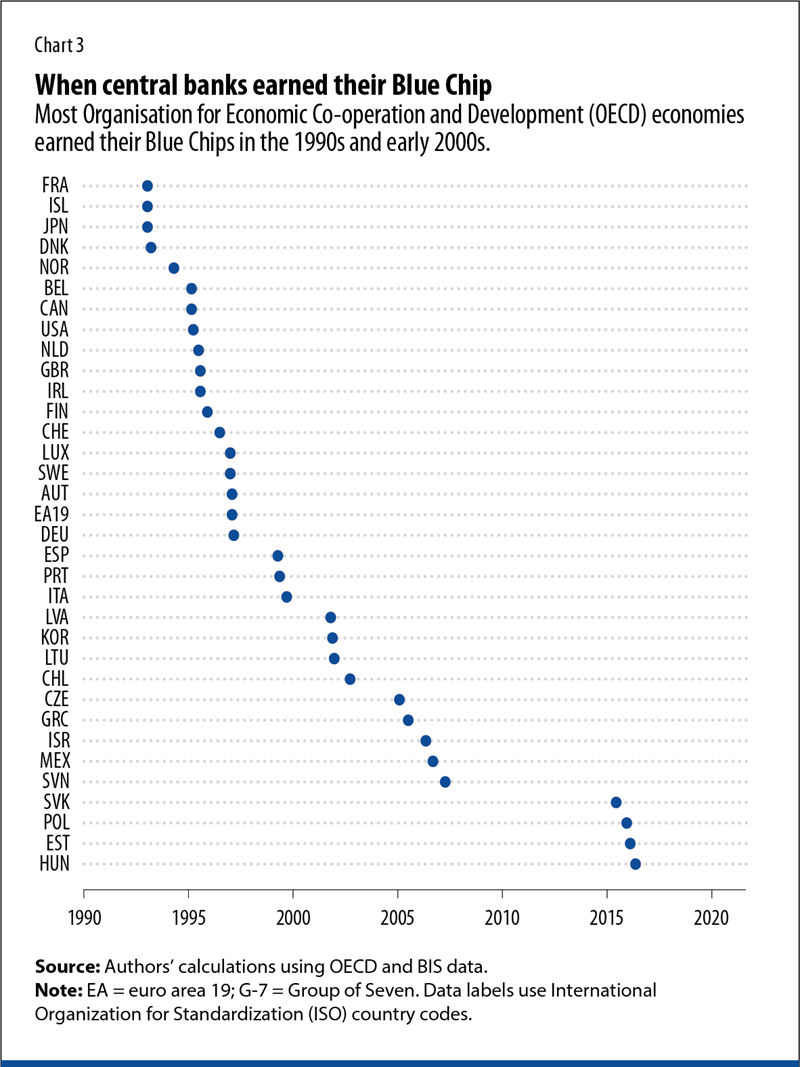

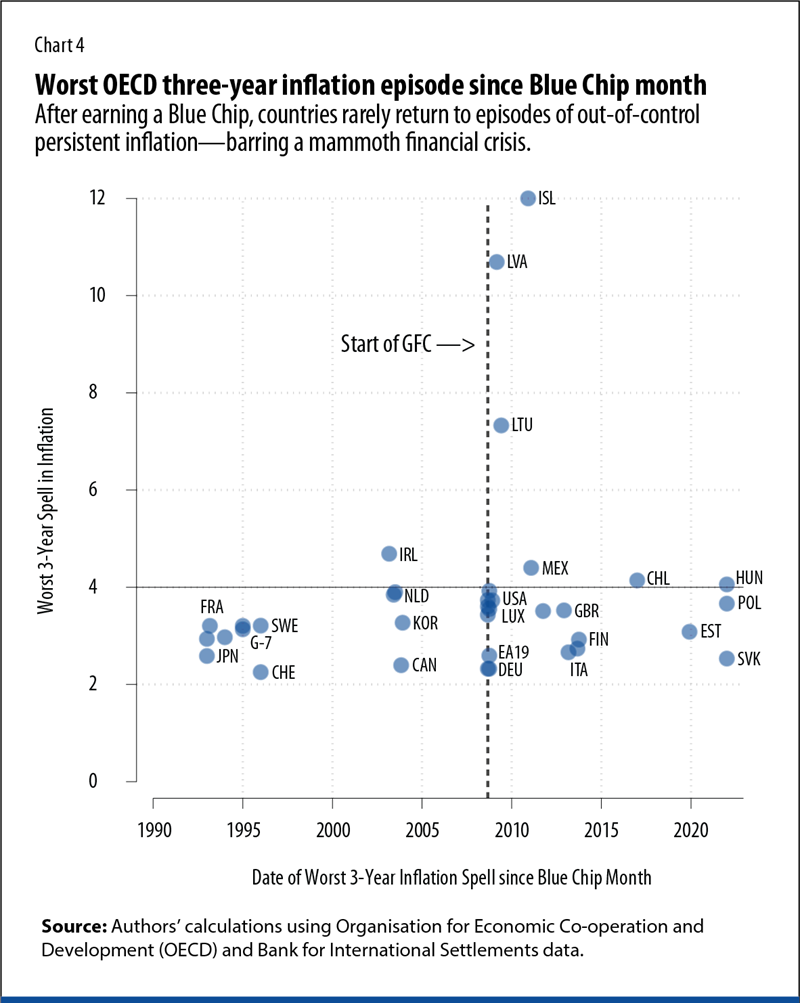

Chart 3 depicts the Blue Chip Month for each Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) country. We do not study emerging markets or low-income countries since only a few have attained Blue Chip status. To date, the only OECD country that has not yet achieved this milestone is Turkey. By “a surge of out-of-control inflation” we mean a 36-month period of inflation above 4 percent. Among OECD countries overall, once a central bank earns a Blue Chip, it rarely returns to out-of-control persistent inflation—unless it experiences a mammoth financial crisis (for example, Iceland and the Baltic states during the global financial crisis). This can be seen in Chart 4, which plots the worst three-year inflation spell in each OECD country after its Blue Chip Month.

One indication of firmly entrenched anti-inflation attitudes is the relative infrequency of central bank employees calling for an increase in the inflation target. More generally, in our view, barring a major crisis, a central bank would have to abandon its dislike of inflation for inflation to get out of control. And experience suggests that it is unlikely that once central banks have brought inflation under control they will stop disliking inflation.

In addition, at least before the pandemic, the reaction functions of advanced economy central banks to inflation are more likely to have a disinflationary bias now that many central banks are acting as if they are constrained by an effective lower bound on interest rates. A consequence of the zero lower bound is that central banks’ actual response has been highly asymmetric above and below the 2 percent target. Central banks tolerate inflation lower than 2 percent but act as if the welfare costs of inflation above 2 percent are high. An implication of this asymmetric bias is that over time inflation expectations have gradually shifted down (even below 2 percent in several countries) and become relatively entrenched, making it harder for short-term high inflation to unanchor them.

Looking ahead

The duration of the current inflation episode will depend on (1) the interplay between the persistence of labor market tightness and supply chain bottlenecks and the central bank response and (2) the duration of the War in Ukraine and its impact on energy prices, food prices, and global growth. If history is any guide, we will not experience an out-of-control surge in inflation beyond a couple of years into the future. (However, some countries may lose their Blue Chips, in large part because of inflation that has already taken place during the pandemic.) Still, there are a few ways in which this assessment can go wrong.

First, central banks’ dislike for inflation may be suppressed given the enduring long-term impact of the pandemic, uncertainty about the recovery, and the temptation to inflate away higher debt burdens globally. Calls to refrain from ending the recovery prematurely cite lower labor force participation compared with pre-pandemic levels. An open question is whether the reaction function has changed post-pandemic. While advanced economy central banks may continue to dislike inflation, their current apparent plans—according to their current dot plots (or the equivalent)—may be behind the curve on what would be required to bring inflation back down. Standard Taylor Rule calculations suggest that it could easily take interest rates as high as 7 percent in several countries to bring inflation down.

Second, John Cochrane (2022) argues that raising rates to fight inflation is a crude tool, especially when the source is fiscal policy. He compares keeping fiscal policy loose and using higher interest rates to control inflation to a driver accelerating and braking at the same time. He argues in effect that if people start to doubt the government’s commitment to repaying its debt without a discount from inflation, inflation could get much worse.

This scenario relies on a combination of (1) debt holders’ marginal propensity to spend rising when they lose confidence in the government’s willingness to pay the debt and (2) a decline in the government’s marginal propensity to cut other spending when interest expenses rise. Conversely, government debt would not contribute to inflation instability if higher interest rates were to reduce government spending (excluding interest payments) more than they raise the spending of government debt holders.

Despite the shocks to the world economy, the behavior of inflation beyond 2025 depends primarily on two things: how determined central banks are to rein in inflation and the bond market’s confidence that governments are willing to pay their debts without inflating them away.

Podcast

Everyone feels the pinch when inflation is on the rise and so the pressure on central banks to manage inflation rates has grown exponentially in recent weeks.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.

References:

Cochrane, J. 2022. “How Government Spending Fuels Inflation.” Wall Street Journal.

Domash, A., and L. H. Summers. 2022. “How Tight Are US Labor Markets? NBER Working Paper 29739, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

Rees, D., and P. Rungcharoenkitkul. 2021. “Bottlenecks: Causes and Macroeconomic Implications.” BIS Bulletin 48.

Krugman, P. 2021. “The Year of Inflation Infamy.” New York Times.

Nakamura, E. 2022. “An Interview with Noah Smith.” Substack.

Summers, L. 2021. ”The Biden Stimulus Is Admirably Ambitious, But It Brings Some Big Risks Too.” Washington Post, February 4.