A newly developed dataset shows how the pandemic’s aftermath ushered in the worst housing affordability crisis in more than a decade

The pandemic and subsequent return of inflation set off the world’s worst housing affordability crisis in more than a decade. It spilled across some of the largest advanced economies and contributed to widespread anger and resentment about economic conditions.

Affordability fell in the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, Germany, Portugal, and Switzerland. On average across countries, housing is less affordable today than during the house price bubble that preceded the global financial crisis of 2007–08, according to a newly developed dataset.

This put housing at the top of households’ list of pressing issues, ahead of health care and education, according to public opinion surveys around the world (Romei and Fleming 2024). It’s a central issue facing policymakers in many countries, given housing’s key role in economic activity. Unlike other assets, housing has a social component, and people often see homeownership as a right of citizenship, even as speculative motives can also drive investment in housing and push up prices.

The affordability crunch reflects higher borrowing costs since central banks jacked up interest rates to counter inflation. At the same time, housing shortages and robust demand amid strong household formation kept prices high. The complex postpandemic economy brought long-simmering structural problems in the global housing market into sharp focus.

Measuring affordability

Housing affordability is a crucial yet subtle concept, especially when it comes to making comparisons among countries with very different housing markets and financing structures. Until now, the most widely used indicators focused on the basic commonsense notion of the relative cost of housing, such as the price-to-income ratio or the share of income spent on housing.

While useful, these indicators do not fully account for mortgage market dynamics and the characteristics of typical housing and household units. My research colleagues Nina Biljanovska and Chenxu Fu and I sought to fill this gap by developing a new cross-country dataset using a mortgage-based indicator of housing affordability (Biljanovska, Fu, and Igan 2023).

The approach focuses on a household’s ability to make regular mortgage payments on a typical property occupied by a family of ordinary size without scrimping on other essential needs. Specifically, our housing affordability index calculates the ratio of actual household income to the level of income required to qualify for a typical mortgage. This offers a more nuanced view of affordability and complements other metrics. A housing affordability index reading above 100 indicates more affordable housing, and lower values signal less affordability.

Postpandemic crisis

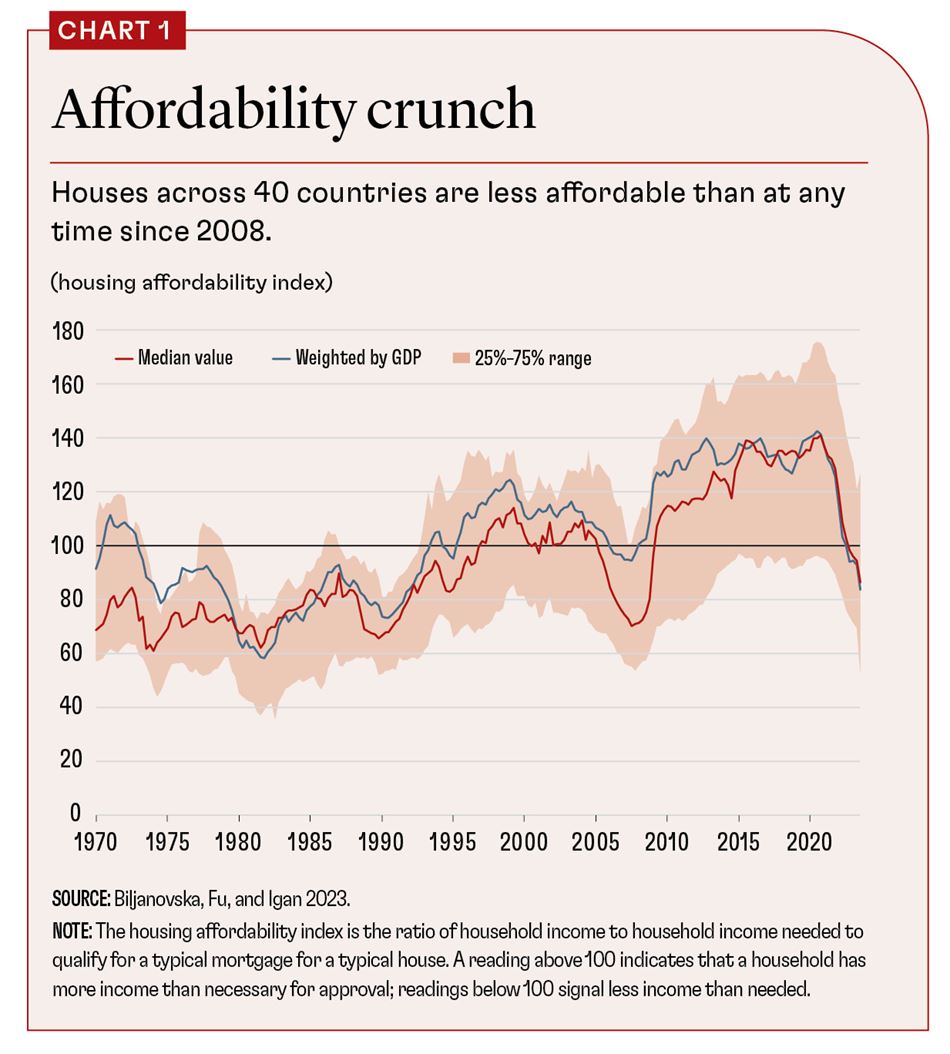

We calculated the index across 40 countries over the past 50 years. What stands out is a sudden deterioration in affordability over the past couple of years. In the US, the world’s largest economy, housing affordability plunged from about 150 in 2021 to the mid-80s by 2024. In the UK, affordability index readings fell from 105 in 2021 to the low 70s in 2024.

Similar declines took place in Austria, Canada, Hungary, Poland, Portugal, Türkiye, and the Baltic countries. This represents a sudden reversal of generally improving affordability over the past several decades. As with resurgent inflation, the dramatic switch in direction had an enormous psychological impact on many households.

How did this happen? During the COVID-19 recession, housing prices surged in many nations (Ahir and others 2022). That was a break with past economic downturns, in which housing markets usually weakened (Igan, Kohlscheen, and Rungcharoenkitkul 2022). It was because of a mix of demand and supply factors, including lockdown-related constraints on construction. The unexpected rapid increase in house prices prompted concerns about an impending correction.

As central banks around the world started raising interest rates to combat inflation, many observers expected the correction to finally take place. House prices did cool somewhat, but much less than expected, even as mortgage rates surged. To understand what is going on, a look into the evolution of housing affordability over time and its drivers is helpful.

Affordability over time

Housing affordability has ebbed and flowed over the past half century. From the 1970s to the mid-1990s, the median affordability index we calculated was below 100, indicating less affordability (see Chart 1). In the late 1990s, affordability improved, consistently topping 100 before deteriorating in the following decade. After the global financial crisis, housing became more affordable again and remained steady until the aftermath of the pandemic.

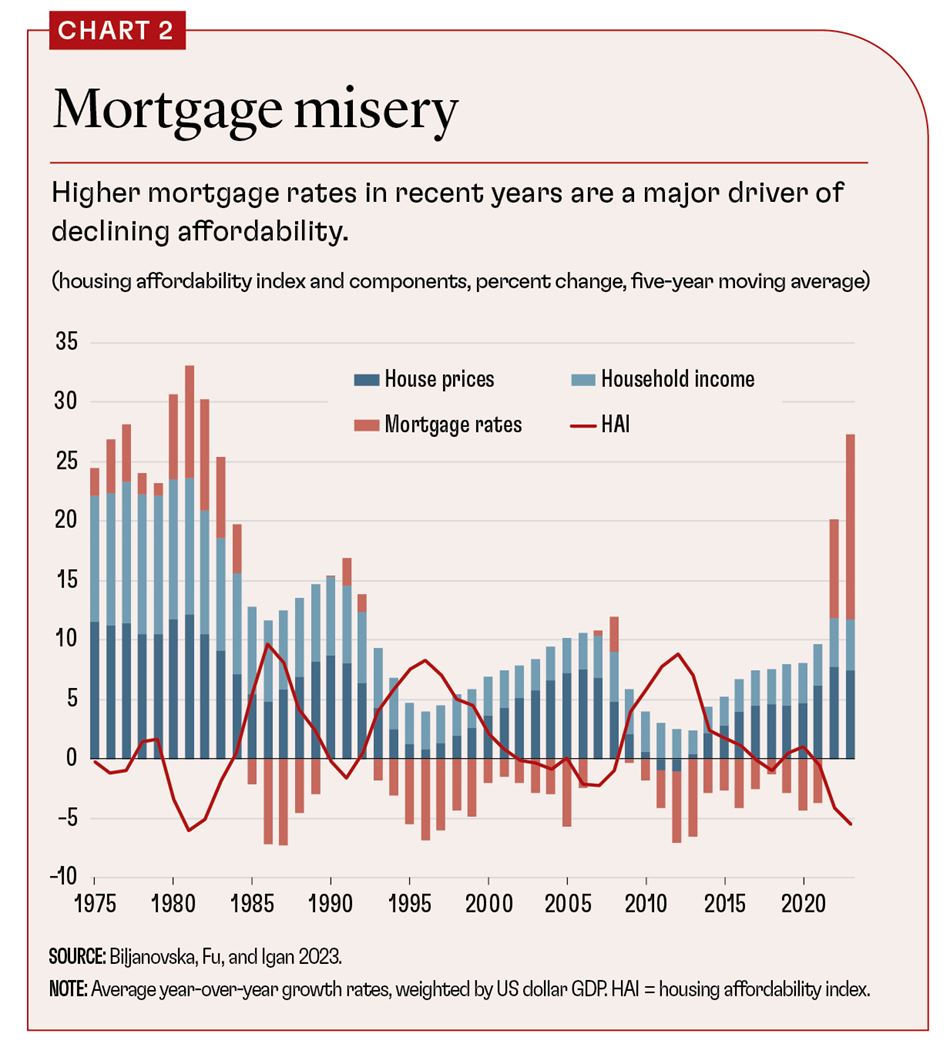

The drivers of these affordability trends are the time-varying components of our index: nominal mortgage rates, household income, and house prices (Chart 2). In the mid-1970s and early 1980s, affordability declined because of rising house prices and borrowing rates. Household incomes didn’t keep up.

During the global financial crisis, housing prices fell, then slowly recovered as central banks embarked on low-for-long interest rates to stimulate ailing economies. The lower borrowing costs and lower housing prices improved affordability during this period.

But then the pandemic reversed the trend, first as house prices surged and then as mortgage rates climbed.

This broad analysis, however, has some limitations. The index focuses on affordability from the perspective of a prospective homeowner looking to finance a purchase with a mortgage, so interest rates play an important role. The metric does not capture affordability along other dimensions, such as outright ownership without a mortgage or renting. The focus on the average household also overlooks crucial differences across the income distribution and across generations.

It also masks country-specific variations. For one, affordability tends to be worse and more volatile in emerging markets, in part reflecting their less developed mortgage markets. Also, reduced borrowing costs benefit mainly households in countries without inflated house prices. In several countries with strong price growth, low interest rates were insufficient to offset the impact of high property prices on affordability. For example, in Belgium, affordability improved as lower rates balanced moderate house price increases. But in Canada, affordability declined due to strong house price growth.

What does the future hold?

The affordability index does not fully address the sustainability of homeownership in the face of interest rate and income shocks. An existing homeowner who would be able to service a mortgage when rates are low may not be able to do so if the rate resets to a higher level. This point is crucial, especially now: the median index improved in the couple of decades before the pandemic mainly due to low interest rates. But this captured only current mortgage affordability. The gains reversed sharply as rates rose.

Can affordability be restored other than through a sharp drop in house prices? Perhaps. Lower mortgage interest rates would help, although that seems unlikely to provide much relief. For one thing, we find that over the half century of our study, changes in mortgage rates accounted for just over a quarter of movements in affordability. For another, most forecasts predict higher long-term interest rates than before the pandemic. Moreover, as rates decline, more households may enter the housing market, increasing demand and pushing up prices (Banerjee and others 2024).

What to do about this? Macroeconomic policymakers could increase the odds of a benign scenario by continuing to usher their economies into a soft landing.

But authorities also need to address the structural problems surrounding housing affordability. Removing regulatory barriers to improve the elasticity of supply could be a first step. An array of rules such as building codes, land use restrictions, and administrative requirements control residential construction and rehabilitation. In many cases, these rules are there for good reason—to mitigate negative externalities and maintain certain quality-of-living standards. But they can also become overly burdensome. For example, building codes might simply enrich materials manufacturers, going beyond what would reasonably meet health and safety considerations.

Structural problems may also reflect a lack of competition in resources, construction, or sales. Policymakers may need to break up oligopolies.

In some cases, more precise policy interventions might help. For instance, governments could consider targeted support for low-income households or those living in informal housing. Incentives for developers to provide affordable units, for instance in the form of extra development rights, could also play a role.

Certainly, the disruptions to housing markets from the pandemic and its aftermath featuring elevated uncertainty and fragile political dynamics should serve as a warning that governments can’t ignore the world’s housing affordability crisis. Accelerating climate change—with sea level rise, widespread wildfires, and extreme weather events—now threatens an already inadequate global supply of housing. And surging migration puts even more stress on shelter and its affordability. Policymakers need to rise to the challenge of making housing affordable again, this time on a sustainable basis through a comprehensive plan.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.

References:

Ahir, Hites, Nina Biljanovska, Chenxu Fu, Deniz Igan, and Prakash Loungani. 2022. “Housing Prices Continue to Soar in Many Countries around the World.” IMF Blog Chart of the Week, October 18.

Banerjee, Ryan, Denis Gorea, Deniz Igan, and Gabor Pinter. 2024. “Housing Costs: A Final Hurdle in the Last Mile of Disinflation?” BIS Bulletin 89 (July 15).

Biljanovska, Nina, Chenxu Fu, and Deniz Igan. 2023. “Housing Affordability: A New Dataset.” BIS Working Paper 1149, Bank for International Settlements, Basel.

Igan, Deniz, Emanuel Kohlscheen, and Phurichai Rungcharoenkitkul. 2022. “Housing Market Risks in the Wake of the Pandemic.” BIS Bulletin 50 (March 10).

Romei, Valentina, and Sam Fleming. 2024. “Concern over Housing Costs Hits Record Highs across Rich Nations.” Financial Times, September 2.