The outlook for Asia and the Pacific in 2024 has brightened: we now expect that the region’s economy will slow less than we previously projected as inflation pressures continue to dissipate.

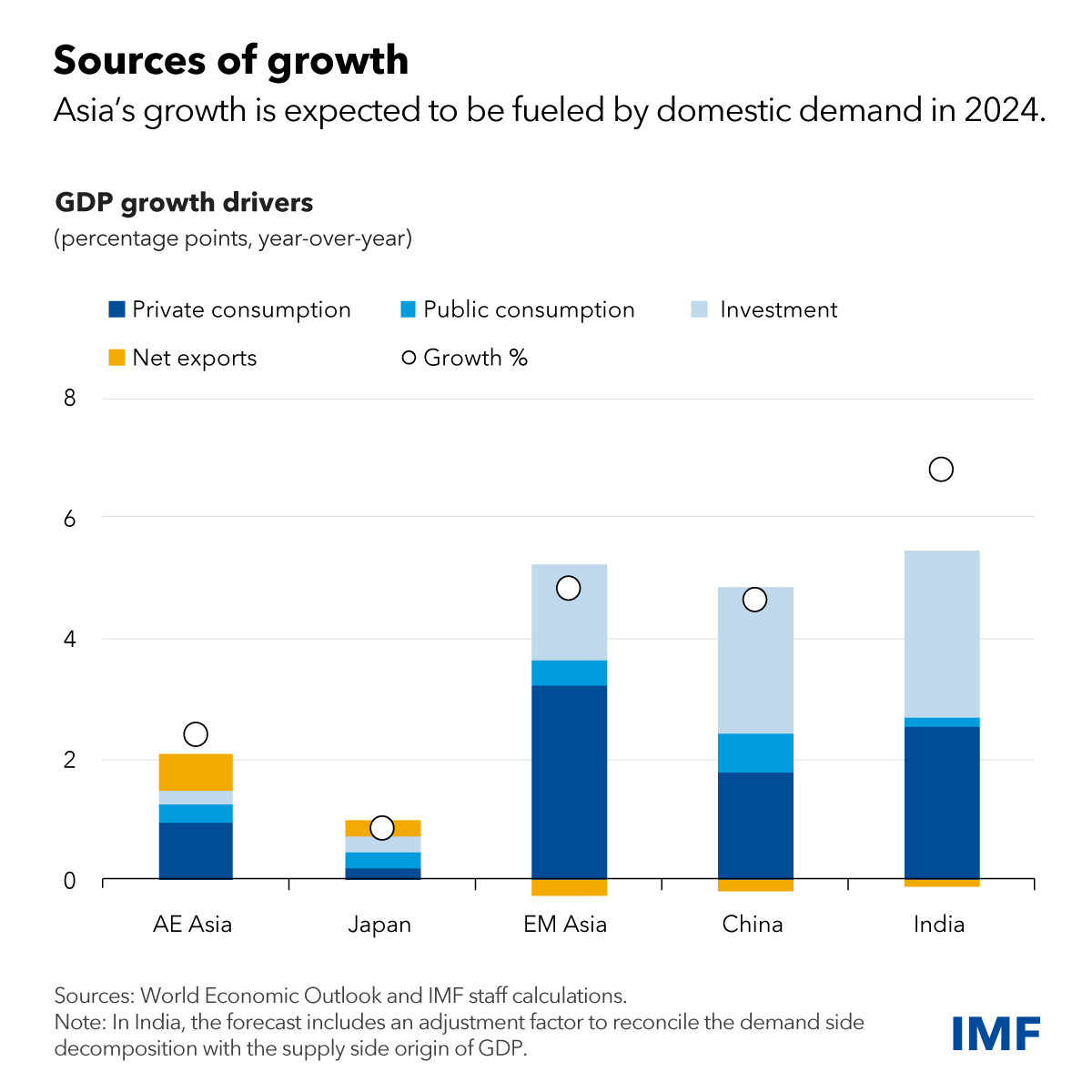

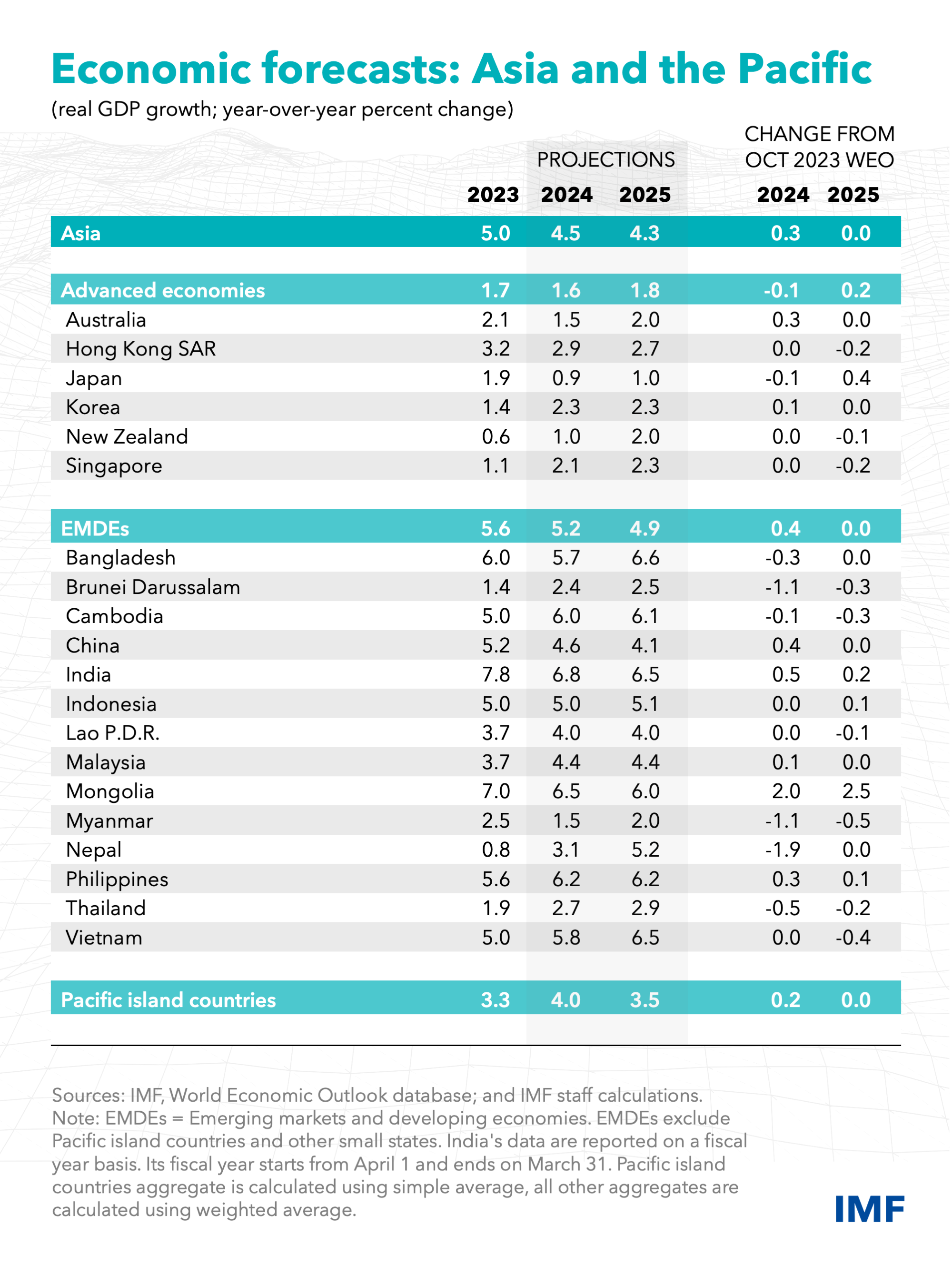

We have raised our regional growth forecast for this year to 4.5 percent, up 0.3 percentage point from six months earlier, after a 5 percent expansion in 2023. The revision reflects upgrades for China, where we expect policy stimulus to provide support, and India, where public investment remains an important driver, making it the world’s fastest-growing major economy. In a still subdued external environment, robust private consumption will remain the main growth driver in Asia’s other emerging market economies. The Asia growth forecast for 2025 is unchanged at 4.3 percent.

Global disinflation and the prospect of lower central bank interest rates have made a soft landing more likely, hence risks to the near-term outlook are now broadly balanced.

A diverse inflation landscape

Despite robust demand growth, inflation in Asia has continued to retreat. The impact of earlier monetary tightening, a global decline in commodity and goods prices, and the abating of supply-chain disruptions after the pandemic all contributed to this outcome.

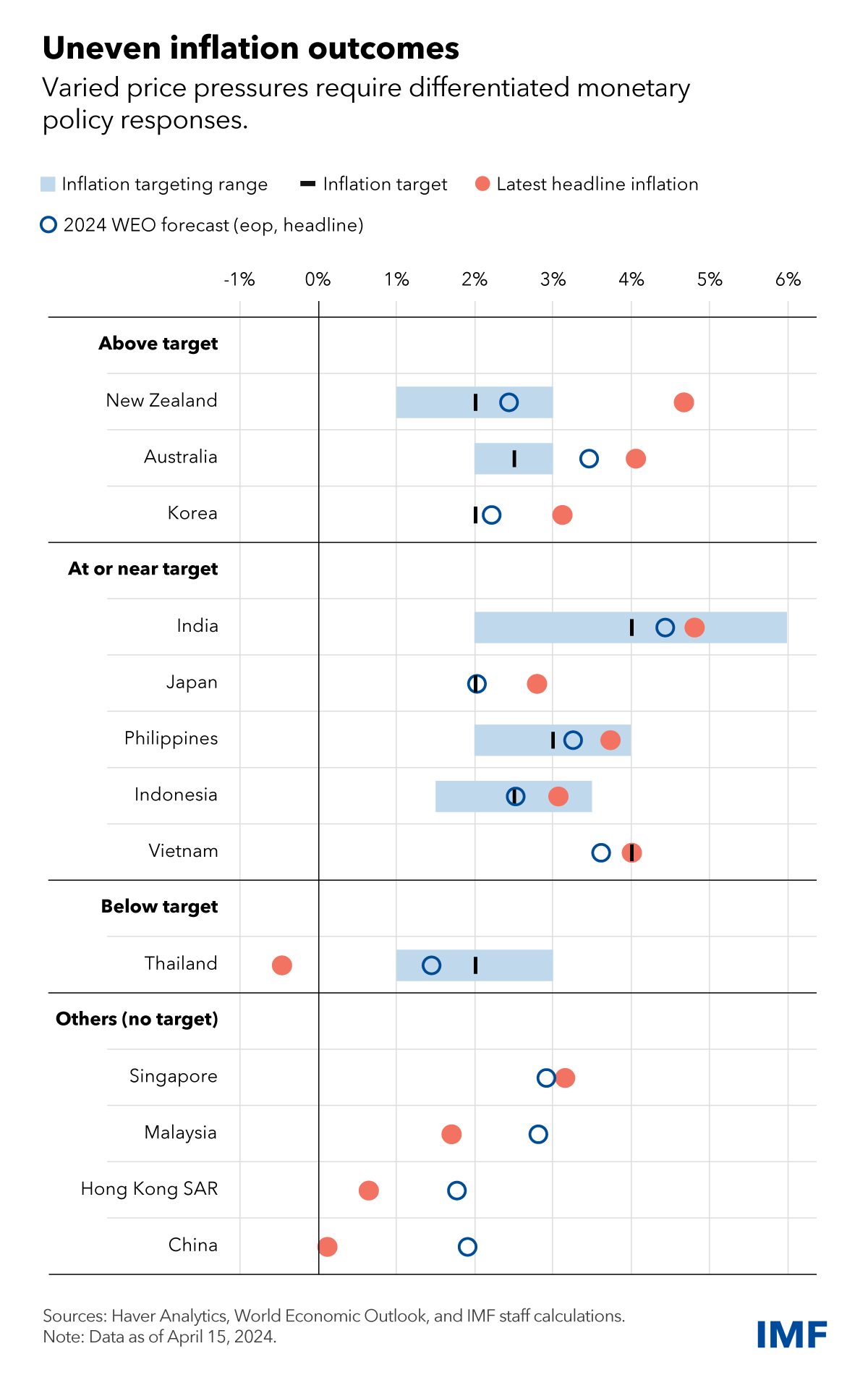

This said, disinflation has been uneven. In some advanced economies—notably New Zealand, Australia, and Korea—persistent services inflation has kept inflation above target. By contrast, in Thailand and China, consumer prices have fallen. Inflation excluding food and energy is low, which, in China, reflects legacy issues from the pandemic and the property sector correction. Elsewhere, inflation is close to target.

This means that countries need differentiated policies. In economies where inflation is still elevated, central banks may need to keep interest rates higher for longer. In economies where core inflation is at or close to target, space for lowering interest rates may emerge later in the year. By contrast, where inflation is undesirably low, an accommodative stance is called for. Central banks should focus firmly on domestic conditions and avoid making decisions overly dependent on the expected path of US interest rates: while following the Federal Reserve could limit exchange rate volatility, it risks that central banks would fall behind (or move ahead of) the curve and destabilize inflation expectations.

Time to tackle public deficits

At the same time, Asian governments need to pursue policies to reduce debt and deficits with greater urgency. Progress last year fell behind what IMF staff had originally projected. Our forecasts show that on current fiscal plans, debt ratios would stabilize for most economies, provided governments underpin these plans with concrete policies and follow through on them. But even then, debt would remain significantly higher than it was before the pandemic.

To reduce debt levels and curtail debt service costs, governments need to streamline expenditures and, especially, raise more revenue. Having to pay less on debt would eventually free up room in the budget for spending on development needs, social safety nets, and climate mitigation and adaptation.

China’s property sector correction

In China, the deepening of the property sector downturn marred the rebound after the country’s post-COVID reopening in early 2023. Even so, the economy grew by 5.2 percent in 2023, more than we previously forecast. Fiscal stimulus enacted last October and in March helped mitigate the impact of declining manufacturing activity and sluggish services. We have raised our growth estimate for this year to 4.6 percent, up by 0.4 percentage points. Since we published our projection, first quarter growth came in stronger than expected, hence this forecast may be revised upward.

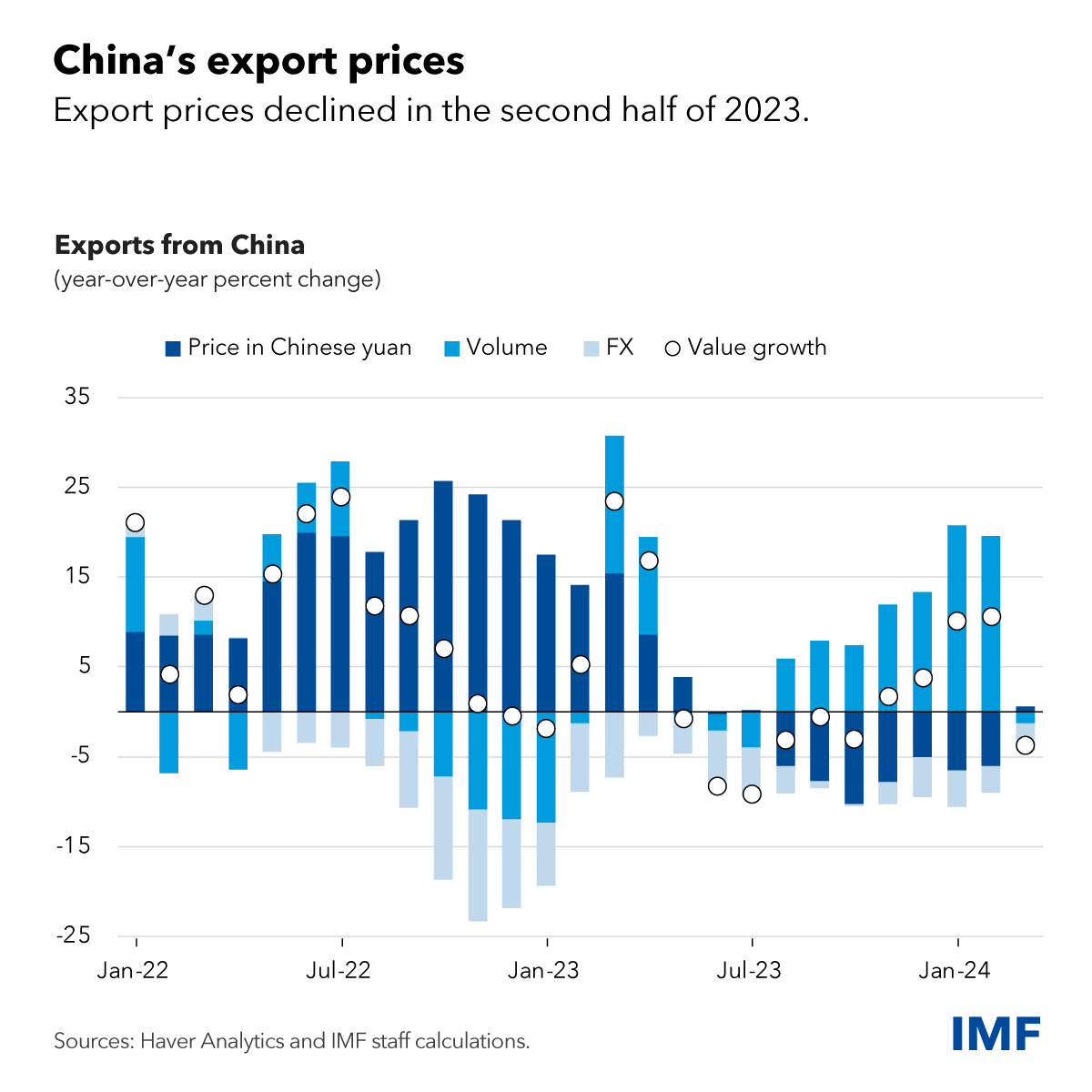

This said, chief among risks for Asia’s economy remains a protracted property sector correction in China that would weaken demand and could increase the odds of sustained deflation. One channel through which this would affect the region is through direct trade spillovers (see the October 2023 Regional Economic Outlook). Another is China’s falling export prices that put pressure on the profit margins of the country’s competitors: recent IMF staff analysis shows that Chinese export price declines reduce both export prices and quantities of other Asian economies, especially those with a similar export structure.

This means China’s policy response matters—for both itself and the entire region. A policy package that accelerates the exit of nonviable property developers, promotes the completion of housing projects, and manages debt risks of local governments would boost confidence, support demand, and help the economy reflate—and therefore improve growth prospects for both China and neighboring countries. By contrast, policies that boost supply—such as investment subsidies to specific companies and industries—would worsen overcapacity, reinforce deflationary pressures, and potentially provoke trade frictions.

Risks to trade

Reinforcing frictions would be a dismal outcome for a region that has benefitted so much from trade openness—as ever more trade-restricting policies are being implemented, both in Asia and elsewhere. One outcome is an inefficient lengthening of supply chains, as trade is channeled through third countries. Global conflict poses additional risks to trade, as evidenced by the re-routing of ships around Africa to avoid the Red Sea, which raises shipment costs. Pacific island countries are especially affected, as they are highly dependent on imports and poorly integrated into global shipping networks.

For Asia’s economies these are unfortunate developments, as many of them are deeply integrated into global supply chains and benefit greatly from trade. Hence policymakers should be cautious to not aggravate trade frictions themselves. For example, we also observe an increasing tendency to implement industrial policy measures. Even though these measures pursue a wide range of objectives, they often include trade-distorting elements. Careful design is needed to avoid unintended side-effects—notably greater fragmentation—and to remain consistent with World Trade Organization rules.

Beyond the short term, population aging, slowing productivity growth, and new technologies such as artificial intelligence confront policymakers in Asia with important challenges. While policy responses need to be tailored to country circumstances, there’s a common need to invest in capital, digital infrastructure, and workforce skills, to preserve Asia’s role as growth engine of the world economy.