As the window of opportunity to contain global warming is closing rapidly, many countries are pursuing policies to reduce emissions. Several rely heavily on spending measures, such as increasing public investment and subsidies for renewable energy. These decarbonization efforts are welcome. Yet, in some cases these policies entail large fiscal costs.

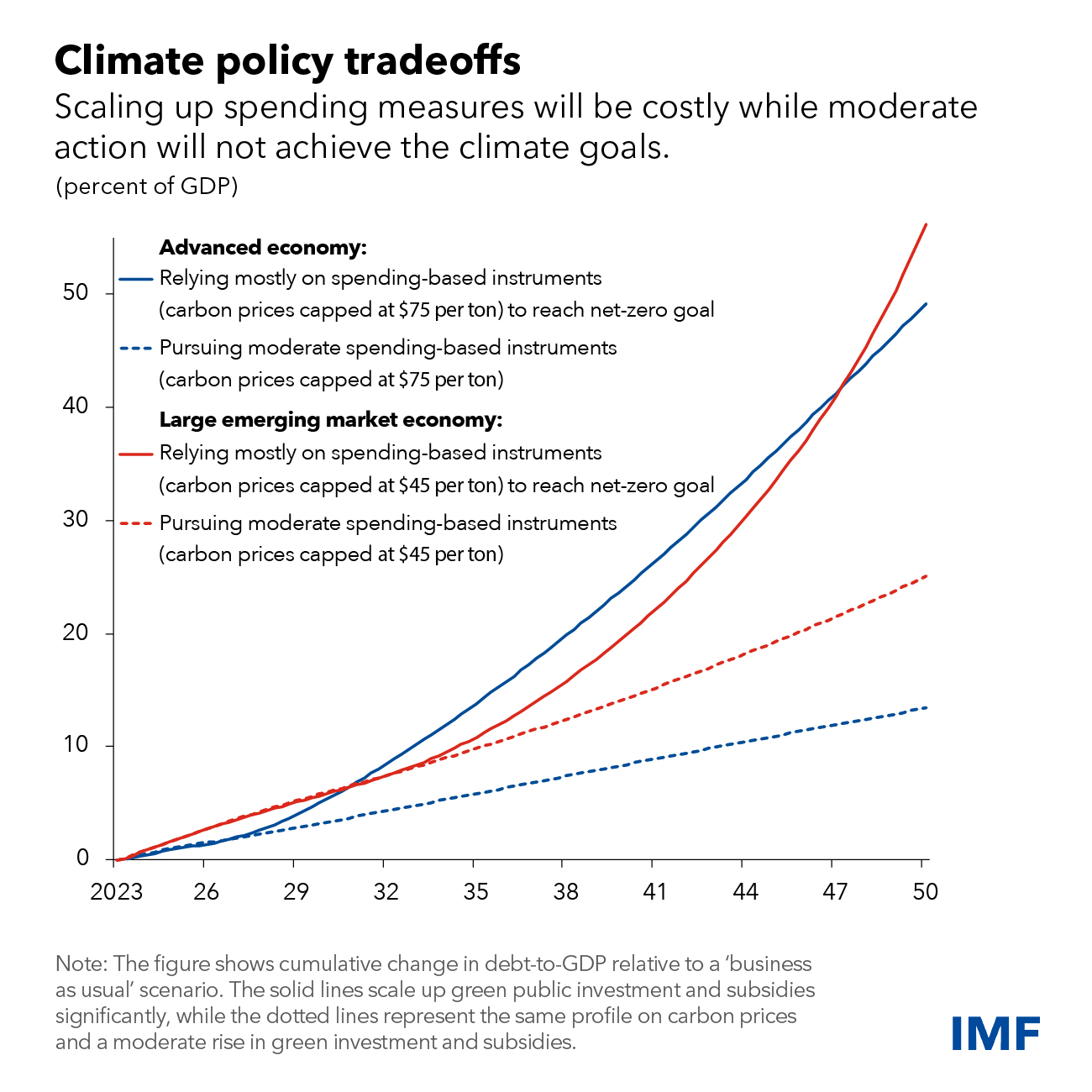

Climate action presents policymakers with difficult tradeoffs. Relying mostly on spending measures and scaling them up to deliver on climate ambitions will become increasingly costly, possibly raising debt by 45 percent to 50 percent of gross domestic product by midcentury. High debt, rising interest rates, and weaker growth prospects will further make public finances harder to balance. But prolonging “business-as-usual” leaves the world vulnerable to warming. Countries have the option to generate revenue to decrease their debt burden through carbon pricing, but relying on carbon pricing alone may cross a political red line.

Governments thus face a policy trilemma between achieving climate goals, fiscal sustainability, and political feasibility.In other words, pursuing any two of these objectives comes at the cost of partially sacrificing the third.

Our latest Fiscal Monitor offers new insights on how to manage this trilemma. Governments must take bold, swift, and coordinated action, and find the optimal mix of both revenue- and spending-based mitigation measures.

Smart policies needed

While no single measure can fully deliver the climate goals, carbon pricing is necessary but not always sufficent to reduce emissions, as also noted by William Nordhaus and others. It should be an integral part of any policy package. Successful experiences from countries at various stages of development, such as Chile, Singapore, and Sweden, show that political hurdles associated with carbon pricing can be overcome. Insights from their experience stand to benefit not only the nearly 50 advanced and emerging market economies with carbon pricing schemes already in place but also the more than 20 countries contemplating their introduction.

But carbon pricing alone is not sufficient and should be complemented by other mitigation instruments to address market failures and promote innovation and deployment of low-carbon technologies. A pragmatic and equitable proposal calls for an international carbon price floor, differentiated across countries at different levels of economic development. The associated carbon revenues could be partly shared across countries to facilitate the green transition. A just transition should also include robust fiscal transfers to vulnerable households, workers, and communities.

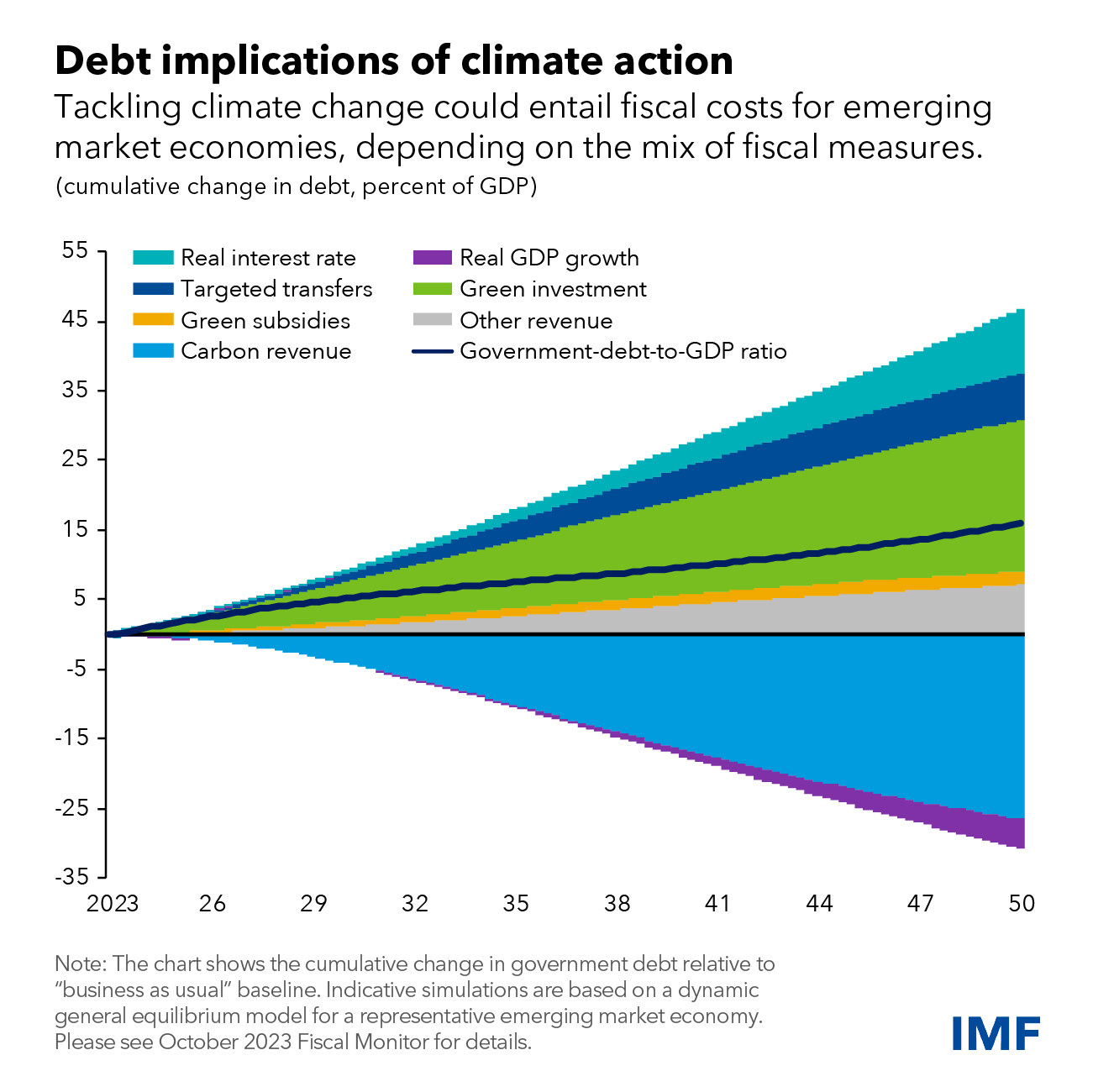

Fiscal costs vary depending on the mix of revenue and spending policies. Our analysis shows that an appropriate mix and sequencing of revenue- and spending-based climate measures enacted now can limit the fiscal costs of emission reductions, while achieving climate goals. We find that public debt in advanced economies would rise by 10 percent to 15 percent of GDP by 2050 without additional revenue or spending measures, though such estimates are subject to large uncertainty, reflecting country differences in government budgets, size of investment and subsidies, compensation to households, and dependence on fossil fuels. Postponing carbon pricing would be costly, adding 0.8 percent to 2 percent of GDP to public debt for each year of delay.

While the expected rise in debt for emerging market economies from a climate policy package is estimated to be similar to that in advanced economies, the contribution from different revenue and spending measures is notably different. That’s because of larger carbon revenue potential but also higher investment needs and higher borrowing costs that are sensitive to the debt level. Economies with sufficient room in government budgets could accommodate such a policy mix. But such an increase in debt would be particularly challenging for most emerging market and developing countries in light of already high debt and rising interest costs, alongside sizable adaptation needs and aspirations to achieve the sustainable development goals.

To navigate these challenges, governments must enhance spending efficiency and build greater capacity for raising tax revenues by broadening the tax base and improving fiscal institutions.

Shared responsibility

No single country can solve the climate threat alone. Nor can the public sector act by itself. The private sector has to fulfill the bulk of the climate financing needs. The Fiscal Monitor discusses the role of firms in the energy transition. Surveys in both Germany and the United States show that firms were resilient to the 2022 energy price spikes, with limited impact on firms’ production and employment, and in many cases, firms adjusted by reducing energy use and investing in energy efficiency.

Policymakers must coordinate their efforts. Emerging market and developing countries face challenges that call for more concessional financing to support the green transition as well as transfers of knowledge and sharing of established low-carbon technologies. For example, the IMF’s Resilience and Sustainability Trust provides long-term financing to strengthen economic resilience and support reforms. Governments should harness the momentum of recent announcements such as the Nairobi Declaration and the participation of the African Union in the Group of Twenty to push forward a practical global deal on an international carbon price floor and support developing countries.