Just this year we’ve seen the increasingly devastating effects of climate change—human tragedy and economic upheaval with typhoons in Bangladesh, unprecedented floods in Pakistan, heatwaves in Europe, wildfires in North America, dry rivers in China, and droughts in Africa.

This will only get worse if we fail to act.

If global warming continues, scientists predict even more devastating disasters and long-term disruption to weather patterns that would destroy lives and livelihoods and upend societies. Mass migration could follow. And, failure to get emissions on the right trajectory by 2030 may lock global warming above 2 degrees Celsius and risk catastrophic tipping points—where climate change becomes self-perpetuating.

If we act now, not only can we avoid the worst, but we can also choose a better future. Done right, the green transformation will deliver a cleaner planet, with less pollution, more resilient economies, and healthier people.

Getting there requires action on three fronts: steadfast policies to reach net zero by 2050, strong measures to adapt to the global warming that’s already locked in, and staunch financial support to help vulnerable countries pay for these efforts.

Net zero by 2050

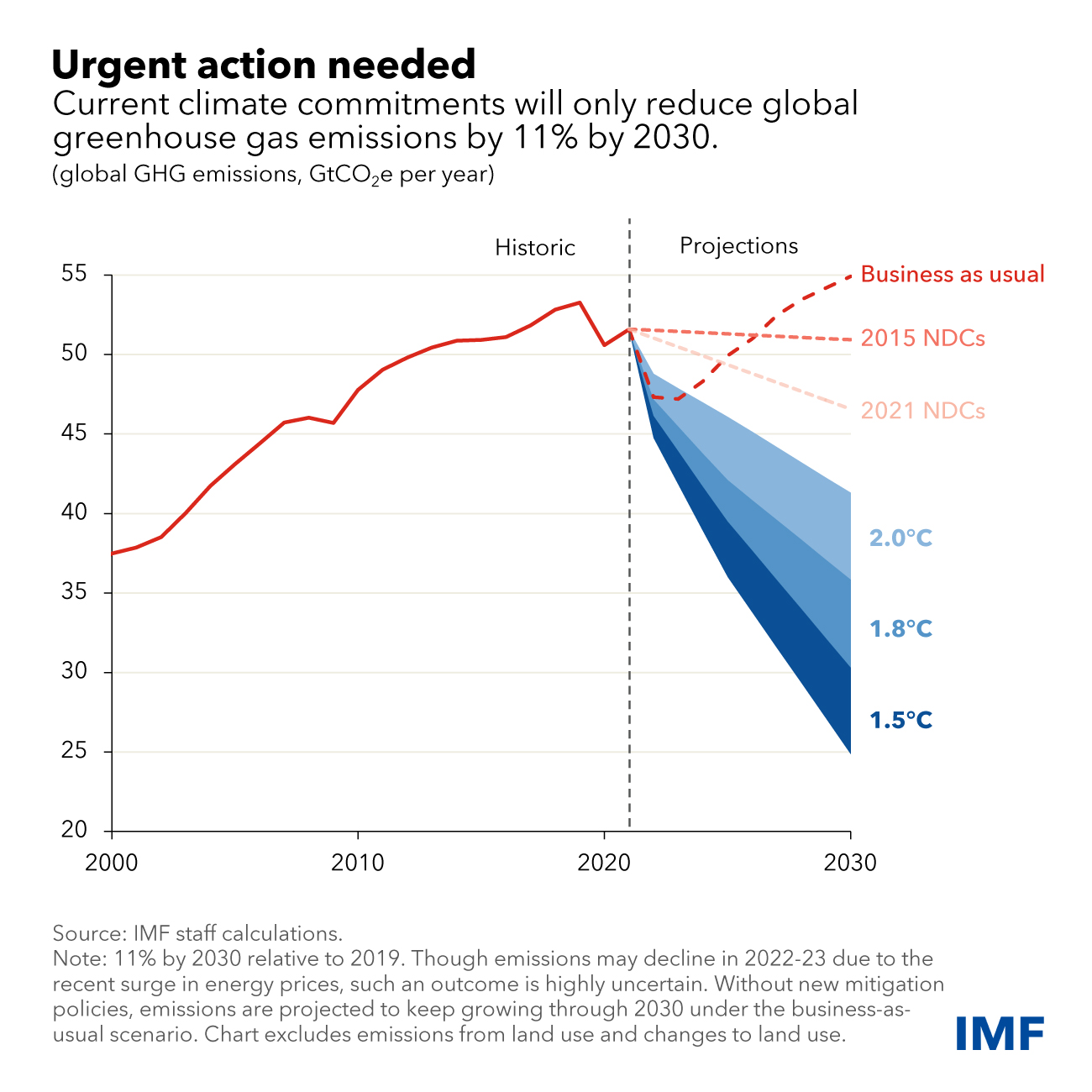

First, it’s vital that we limit further temperature rises to 1.5 degrees to 2 degrees. Delivering on that by 2050 requires cutting emissions by 25‑50 percent by 2030 compared to pre-2019 levels.

The good news is that about 140 countries—accounting for 91 percent of greenhouse gas emissions—have already proposed or set net-zero targets for around mid-century.

The bad news is that net-zero rhetoric does not match reality.

Actually getting to net zero by 2050 means most countries need to do even more to strengthen their targets for cutting emissions—particularly large economies.

And there is an even bigger gap on the policy front. New IMF analysis of current global climate targets shows they would only deliver an 11 percent cut. The gap between that and where we need to be is massive—equivalent to more than five times the current annual emissions of the European Union.

We desperately need implementation to catch up.

That will require a mix of incentives to push firms and households to prioritize clean goods and technologies across all their decisions.

The ideal policy mix would include pricing carbon, including cutting fossil fuel subsidies, along with alternative measures that can achieve equivalent outcomes, such as feebates and regulations. To complement domestic policies, an international carbon price floor agreement would provide one way of galvanizing action: asking large emitters to pay a minimum price of $25-$75 per ton of carbon depending on their national income level. And with alternative policies, this does not mean taxes per se. It would be collaborative, pragmatic, and equitable.

Of course, the overall policy package should include measures to reduce methane. Cutting these emissions by half over the next decade would prevent an estimated 0.3 degree rise in the average global temperature by 2040—and help avoid tipping points.

It is also critical to include incentives for private investments in low-carbon technologies, growth-friendly public investments in green infrastructure, and support for vulnerable households.

The new IMF analysis has encouraging projections for an equitable package that would contain global warming to 2 degrees. We estimate that the net cost of moving to clean technology—including the savings made by avoiding unnecessary investments in fossil fuels—would be around 0.5 percent of global gross domestic product in 2030. This is a tiny amount in comparison the devastating costs of unchecked climate change.

But the longer we wait, making the shift would be far more costly and more disruptive.

Urgent need to adapt

But mitigation action is not enough. With some global warming already locked in, people and economies everywhere are paying the price every day.

And, while the world’s larger economies contribute the most and must deliver the lion’s share of cuts to global greenhouse gases, smaller economies pay the biggest costs and face the biggest bill for adaptation.

In Africa, a single drought can lower a country’s medium-term economic growth potential by 1 percentage point, creating a government revenue shortfall equivalent to a tenth of the education budget.

This underscores the importance of broad investments in resilience — from infrastructure and social safety nets to early warning systems and climate-smart agriculture. In fact, for around 50 low-income and developing economies, the IMF estimates annual adaption costs will exceed 1 percent of GDP for the next 10 years.

In many cases, these countries have exhausted fiscal space during nearly three years of crises ranging from the pandemic to rampant inflation. They urgently need international financial and technical support to build resilience and get back on their development paths.

Climate finance: innovate now

Doing more on climate financing is also vital. Advanced economies must meet or exceed the pledge of $100 billion in climate finance for developing countries—not least for equity reasons.

But public money alone is not enough—so innovative approaches and new policies to incentivize private investors to do more. After all, the green transformation brings vast opportunities for investments in infrastructure, energy, and more.

It starts with stronger governance and integrating climate considerations into public investment and financial management that can help unlock new sources of financing.

Proven financial instruments will also be important—such as closed-end investment funds that can pool emerging market assets to provide scale and diversify risks. And multilateral development banks or donors must do more to encourage institutional investors to come in—for example, by providing equity, which currently makes up only a small share of their commitments.

One promising new area: unlocking capital from pension funds, insurance companies and other long-term investors that collectively manage over $100 trillion of assets.

Another consideration is how better data facilitates decision and investment. That’s why the IMF and other global bodies are standardizing high-quality and comparable information for investors, harmonizing climate disclosures, and aligning financing with climate-related goals.

Role of the IMF

The IMF recognizes that the critical importance of the green transformation, and we have stepped up on this issue, including through our partnerships with the World Bank, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Network for Greening the Financial System, and others.

We are already incorporating climate considerations in all aspects of our work. This includes economic and financial surveillance, data, and capacity development, together with analytical work. And our first ever long-term financing tool, the Resilience and Sustainability Trust, now has more than $40 billion in funding pledges, along with three staff-level agreements with Barbados, Costa Rica, and Rwanda.

The support for this instrument shows the enduring power of cooperation to overcome global challenges.

If we don’t act now, then the devastation and destruction of climate change—and the threat to our very existence—will only get worse.

But if we work together—and work harder and faster—a greener, healthier, and more resilient future is still possible.