Inflation in some economies is rising at the fastest pace in four decades, while tight labor markets have boosted pay gains. That has raised concerns that these conditions could become self-reinforcing and lead to a wage-price spiral—a prolonged loop in which inflation leads to higher wage growth, fueling even higher inflation.

An examination of recent wage dynamics and the prospect of such a wage-price spiral are the subjects of an analytical chapter of our latest World Economic Outlook, which finds that, on average, the risks of a spiral are limited—so far. Three factors are working together to contain the risks: the underlying shocks to inflation are coming from outside the labor market, falling real wages are helping to reduce price pressures, and central banks are aggressively tightening monetary policy.

A look at history

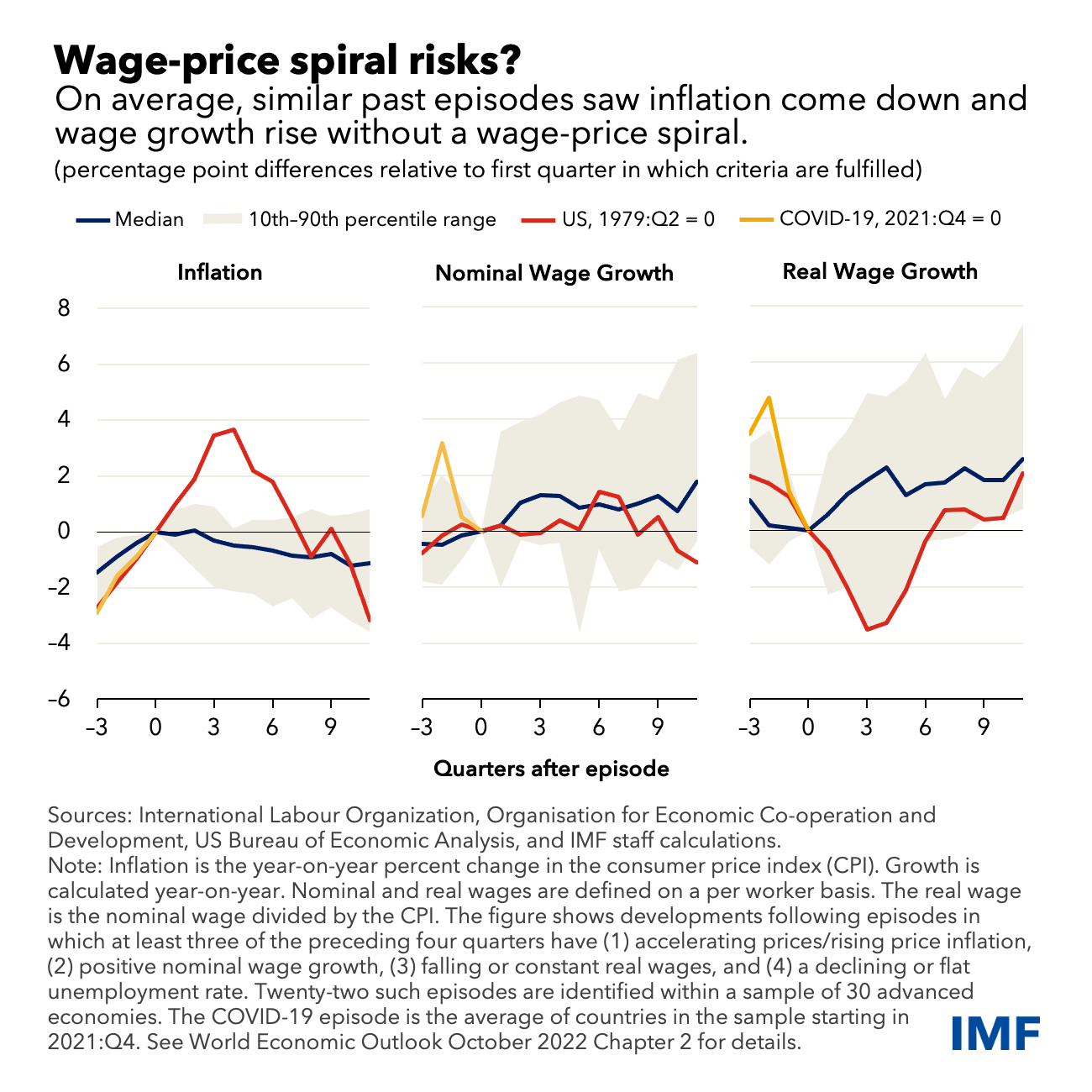

To better understand these dynamics, we identified 22 situations in advanced economies over the past 50 years with conditions similar to 2021 when price inflation was rising, wage growth was positive, but real wages and the unemployment rate were flat or falling. These episodes didn’t lead to wage-price spirals on average. Instead, inflation came down in subsequent quarters and nominal wages gradually rose, helping real wages recover.

Although the shocks hitting economies are unusual, these findings provide some reassurance that sustained wage-price spirals are rare. But that should not be cause for complacency by policymakers—there are differences across episodes, with some showing worse outcomes. Inflation in the United States, for example, kept rising and real wages fell for a while after 1979, when the economy was hit by further oil price hikes. The inflation trajectory changed only when the Federal Reserve raised interest rates sharply.

The role of expectations

How expectations are formed matters a lot for wage and price dynamics and affects what actions policymakers should take after an inflationary shock. Inflation expectations became more important in explaining wage dynamics over the second half of 2021, according to an empirical analysis.

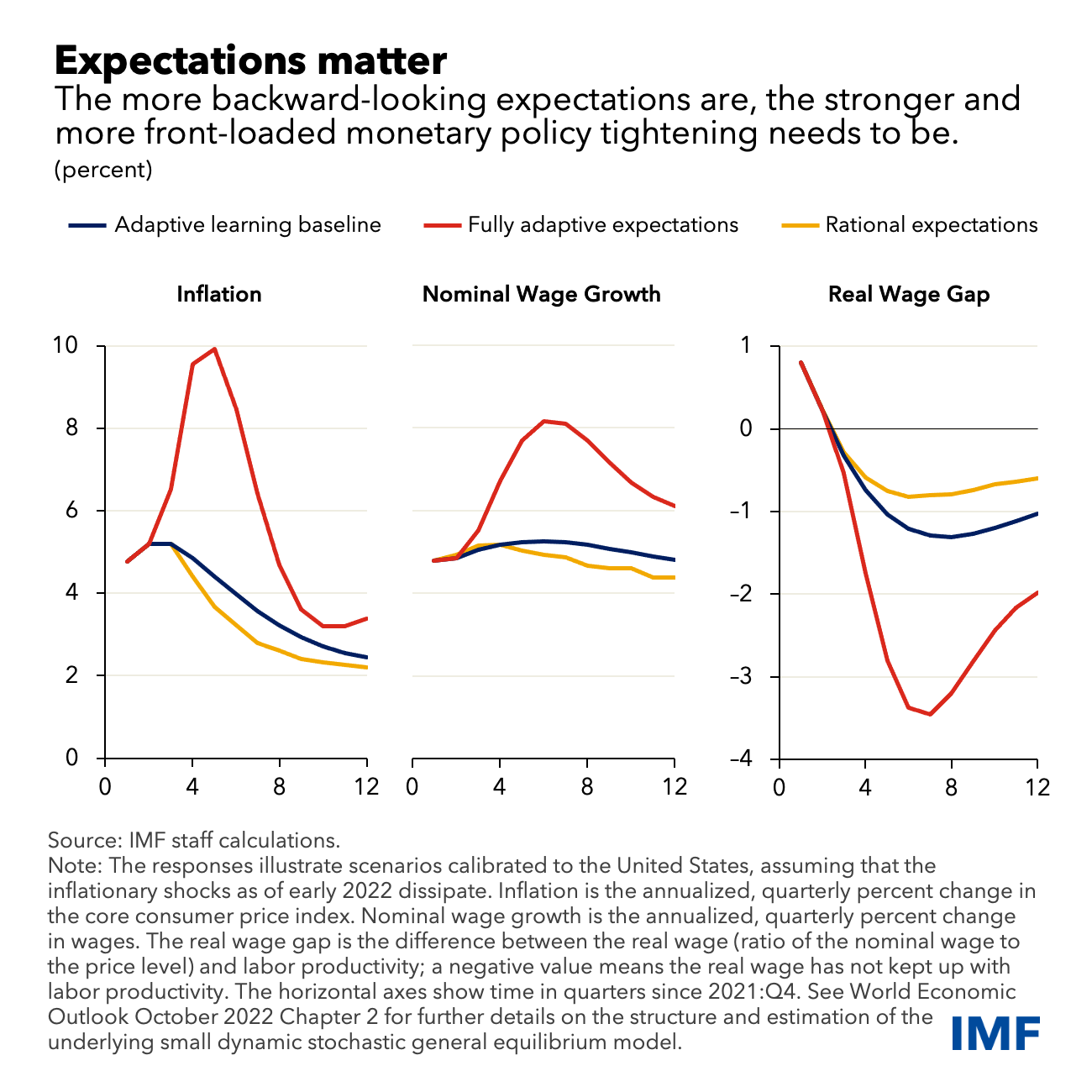

To study how expectations affect the economy, we used a model-based analysis, calibrated to reflect economic conditions in the first half of this year and taking the policy rate path as given.

When businesses and households expect future inflation to be the same as it is today, an inflationary shock can lead workers to demand even more to compensate for perceived higher future inflation. This kind of backward-looking expectations process—what we refer to as fully adaptive—can lead inflation to rise and stay above the central bank’s inflation target for a prolonged period even if there are no additional price shocks.

By contrast, when people’s expectations reflect all available economic information—referred to as rational—businesses and households see the shock to wages and prices as temporary, leading wage growth and inflation to quickly move back towards target and stay anchored. In most places, the reality lies somewhere between these extremes, with businesses and households looking at what happened in the past (weighing recent quarters more heavily) to learn about the economy’s structure and make predictions, referred to as adaptive learning. In this case, wage growth and inflation can take longer to come back to the central bank’s target than when expectations are rational, but faster than when they are fully adaptive.

In all these cases, real wages tend to go down initially as inflation outstrips wage growth, helping offset some of the cost-push shock that fueled inflation and working against a wage-price spiral. But if inflationary shocks start to come from the labor market itself—such as an unexpected, sharp uptick in wage indexation—that could moderate the effects of falling real wages, pushing up both wage growth and inflation for longer.

For monetary policymakers, understanding the expectations process is critical. When expectations are more backward-looking, monetary policy tightening—including through clear communications by the central bank—should be stronger and more front-loaded in response to an inflation shock.

In that sense, recent tightening actions by many central banks—calibrated to economy-specific circumstances—are encouraging. They will help to prevent high inflation from becoming entrenched and inflation from deviating from target for too long.

— This blog is based on Chapter 2 of the October 2022 World Economic Outlook, “Wage Dynamics Post-COVID-19 and Wage-Price Spiral Risks.” The authors of the report are Silvia Albrizio, Jorge Alvarez, Alexandre Balduino Sollaci, John Bluedorn (lead), Allan Dizioli, Niels-Jakob Hansen, and Philippe Wingender, with support from Youyou Huang and Evgenia Pugacheva.