The global economy, still reeling from the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, is facing an increasingly gloomy and uncertain outlook. Many of the downside risks flagged in our April World Economic Outlook have begun to materialize.

Higher-than-expected inflation, especially in the United States and major European economies, is triggering a tightening of global financial conditions. China’s slowdown has been worse than anticipated amid COVID-19 outbreaks and lockdowns, and there have been further negative spillovers from the war in Ukraine. As a result, global output contracted in the second quarter of this year.

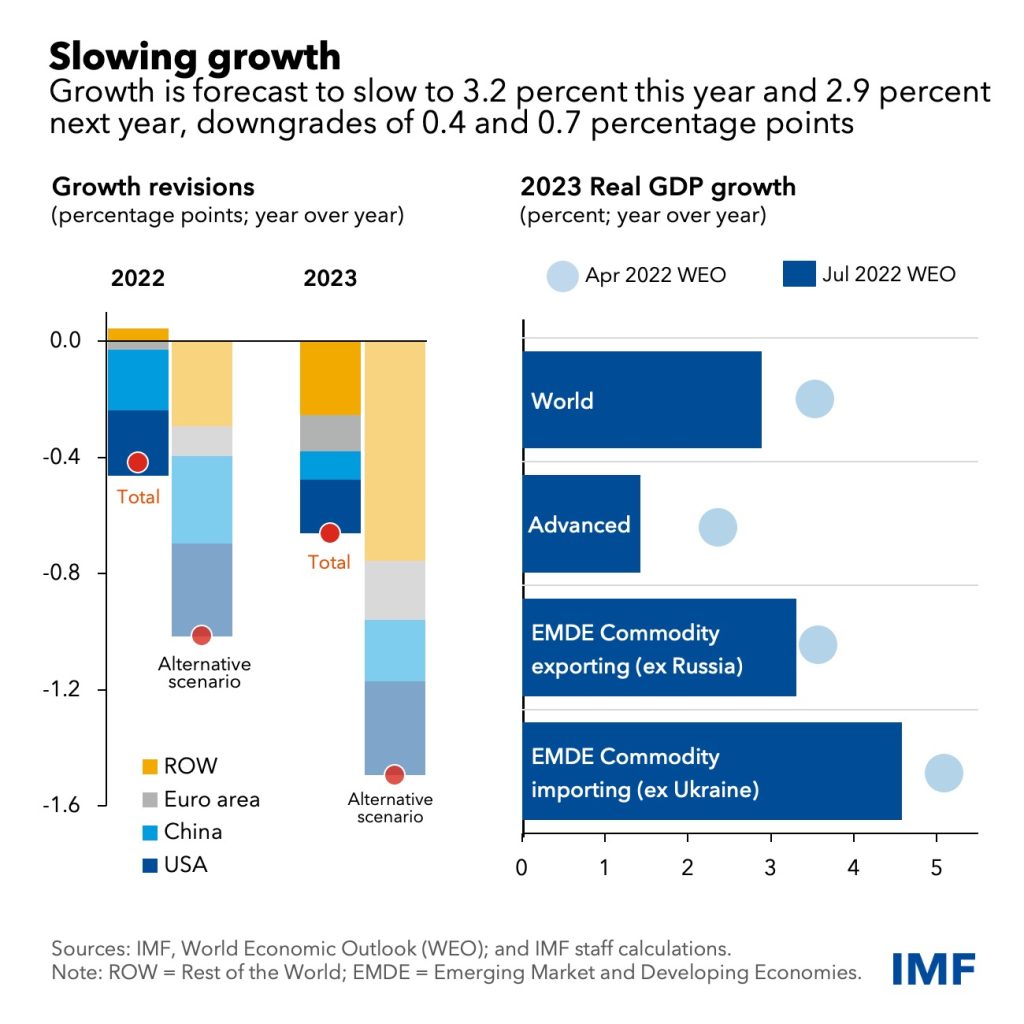

Under our baseline forecast, growth slows from last year’s 6.1 percent to 3.2 percent this year and 2.9 percent next year, downgrades of 0.4 and 0.7 percentage points from April. This reflects stalling growth in the world’s three largest economies—the United States, China and the euro area—with important consequences for the global outlook.

In the United States, reduced household purchasing power and tighter monetary policy will drive growth down to 2.3 percent this year and 1 percent next year. In China, further lockdowns, and the deepening real estate crisis pushed growth down to 3.3 percent this year—the slowest in more than four decades, excluding the pandemic. And in the euro area, growth is revised down to 2.6 percent this year and 1.2 percent in 2023, reflecting spillovers from the war in Ukraine and tighter monetary policy.

Despite slowing activity, global inflation has been revised up, in part due to rising food and energy prices. Inflation this year is anticipated to reach 6.6 percent in advanced economies and 9.5 percent in emerging market and developing economies—upward revisions of 0.9 and 0.8 percentage points respectively—and is projected to remain elevated longer. Inflation has also broadened in many economies, reflecting the impact of cost pressures from disrupted supply chains and historically tight labor markets.

The risks to the outlook are overwhelmingly tilted to the downside:

- The war in Ukraine could lead to a sudden stop of European gas flows from Russia

- Inflation could remain stubbornly high if labor markets remain overly tight or inflation expectations de-anchor, or disinflation proves more costly than expected

- Tighter global financial conditions could induce a surge in debt distress in emerging market and developing economies

- Renewed COVID-19 outbreaks and lockdowns might further suppress China’s growth

- Rising food and energy prices could cause widespread food insecurity and social unrest

- Geopolitical fragmentation might impede global trade and cooperation.

In a plausible alternative scenario where some of these risks materialize, including a full shutdown of Russian gas flows to Europe, inflation will rise and global growth decelerate further to about 2.6 percent this year and 2 percent next year—a pace that growth has fallen below just five times since 1970. Under this scenario, both the United States and the euro area experience near-zero growth next year, with negative knock-on effects for the rest of the world.

Policy priorities

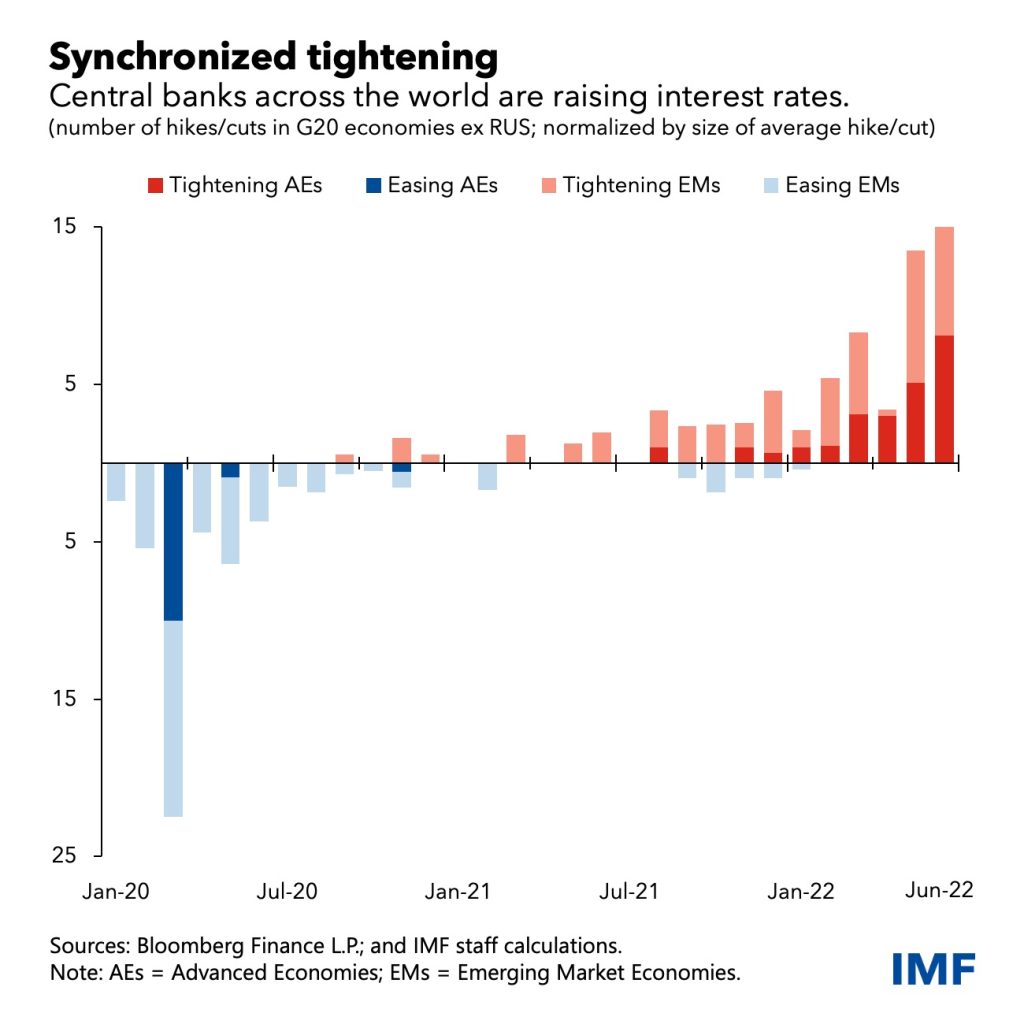

Inflation at current levels represents a clear risk for current and future macroeconomic stability and bringing it back to central bank targets should be the top priority for policymakers. In response to incoming data, central banks of major advanced economies are withdrawing monetary support faster than we expected in April, while many in emerging market and developing economies had already started raising interest rates last year.

The resulting synchronized monetary tightening across countries is historically unprecedented, and its effects are expected to bite, with global growth slowing next year and inflation decelerating. Tighter monetary policy will inevitably have real economic costs, but delaying it will only exacerbate the hardship. Central banks that have started tightening should stay the course until inflation is tamed.

Targeted fiscal support can help cushion the impact on the most vulnerable. But with government budgets stretched by the pandemic and the need for an overall disinflationary macroeconomic policy stance, offsetting targeted support with higher taxes or lower government spending will ensure that fiscal policy does not make the job of monetary policy even harder.

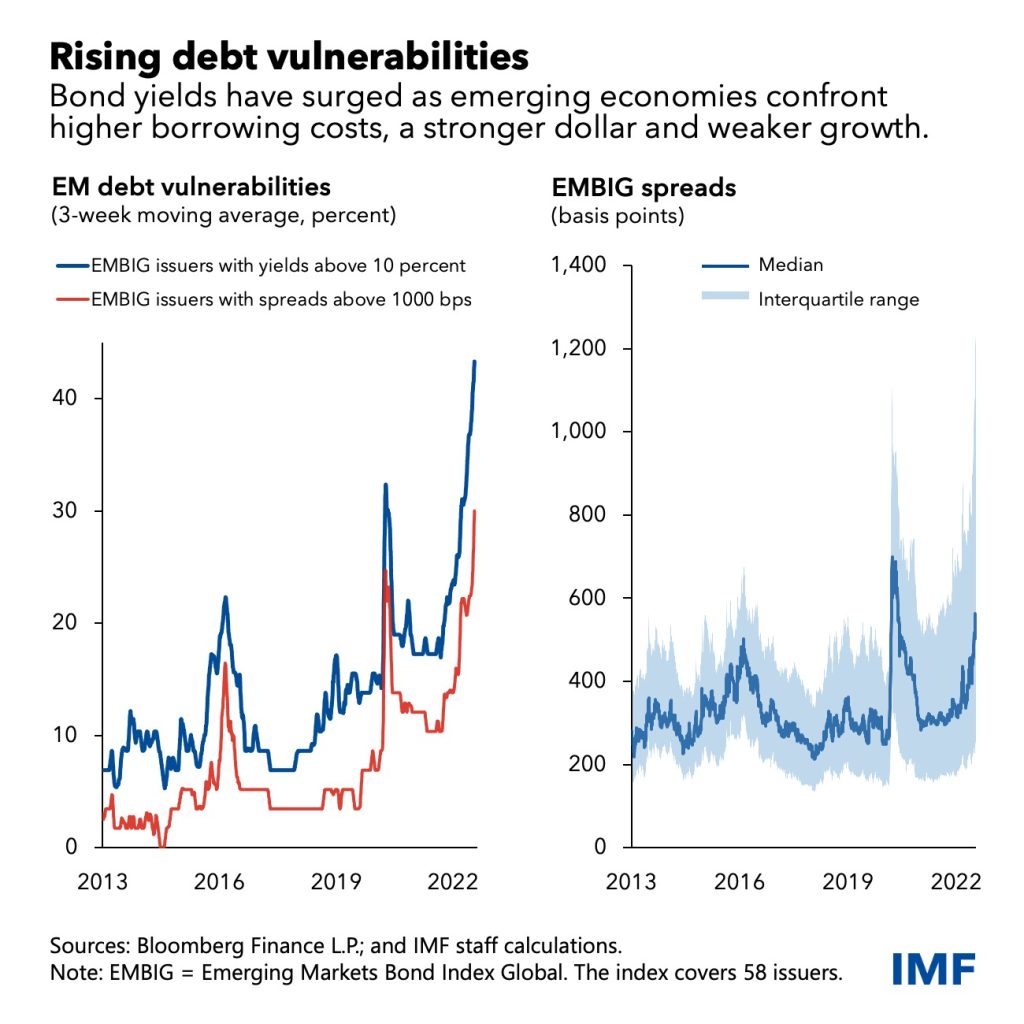

As advanced economies raise interest rates to fight inflation, financial conditions are tightening, especially for their emerging-market counterparts. Countries must appropriately use macroprudential tools to safeguard financial stability. Where flexible exchange rates are insufficient to absorb external shocks, policymakers will need to be ready to implement foreign exchange interventions or capital flow management measures in a crisis scenario.

Such challenges come at a time when many countries lack fiscal space, with the share of low-income countries in or at high risk of debt distress at 60 percent, up from about 20 percent a decade ago. Higher borrowing costs, diminished credit flows, a stronger dollar and weaker growth will push even more into distress.

Debt-resolution mechanisms remain slow and unpredictable, hampered by difficulties in obtaining coordinated agreements from diverse creditors over their competing claims. Recent progress in implementing the Group of Twenty’s Common Framework is encouraging, but further improvements are still urgently needed.

Domestic policies to address the impacts of high energy and food prices should focus on those most affected without distorting prices. Governments should refrain from hoarding food and energy and instead look to unwind barriers to trade such as food export bans, which drive world prices higher. As the pandemic continues, governments must step up vaccination campaigns, resolve vaccine distribution bottlenecks and ensure equitable access to treatment.

Finally, mitigating climate change continues to require prompt multilateral action to limit emissions and raise investment to hasten the green transition. The war in Ukraine and soaring energy prices have put pressure on governments to turn to fossil fuels such as coal as a stopgap measure. Policymakers and regulators should ensure such measures are temporary and only cover energy shortfalls, not increase emissions overall. Credible and comprehensive climate policies to increase green energy supply should be accelerated urgently. The energy crisis also illustrates how a policy of clean, green energy independence can be compatible with national security objectives.

The outlook has darkened significantly since April. The world may soon be teetering on the edge of a global recession, only two years after the last one. Multilateral cooperation will be key in many areas, from climate transition and pandemic preparedness to food security and debt distress. Amid great challenge and strife, strengthening cooperation remains the best way to improve economic prospects and mitigate the risk of geoeconomic fragmentation.