Digital public infrastructure can drive a sustainable increase in revenue collection and build trust in government

Countries all over the world are facing an uphill battle to help citizens protect themselves against economic shocks caused by climate change, global geopolitical fractures, and pandemics while also supporting inclusive and climate-resilient growth. For governments in developing economies, these battles are harder, and the options fewer.

The IMF estimates that low-income developing countries need $3 trillion annually through 2030 to finance their development goals and the climate transition. And with global debt projected to reach 100 percent of GDP before the end of this decade, borrowing to finance these investments may not be the soundest choice. Given that these countries have an untapped tax potential of 8–9 percent of GDP, collecting more revenue through taxation is a better solution.

Yet increasing tax revenue is a major challenge in poorer countries. A large share of the population works in difficult-to-tax activities such as small-holder farming and as informal service providers, such as street vendors. It is difficult for the government to track these earnings because they are largely cash-based. These workers often believe that joining the formal sector will only bring them greater tax liability and limited benefits. They prefer to keep businesses small and informal.

To grow their industries, governments often resort to offering tax exemptions to large corporations, which erodes the corporate tax base and strengthens vested interests. Consequently, such countries rely mainly on taxes on goods and services, which place a heavier burden on the poor. Moreover, revenue collection is too often characterized by enforcement that is weak for the rich and punitive for the working class and the poor.

Delivering value

We propose a different and more sustainable approach to increasing domestic revenue in developing economies. This approach is founded on the belief that how governments drive increases in tax collection is integral to how much tax they can collect. The approach is based on strengthening the social contract and encouraging individuals and businesses to formalize their economic activities, with early lessons from India.

A recent World Bank report—supported by funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation—presents a tax administration framework in which governments augment their efforts to improve enforcement with efforts to build trust by generating social value for their citizens. Generating value as a tax reform strategy is especially important in poorer countries, where trust in tax authorities is limited, compliance is poor, and political support for taxation is low.

The report, “Innovations in Tax Compliance: Building Trust, Navigating Politics, and Tailoring Reform,” examines how tax reform has traditionally sought to strengthen enforcement by detecting tax evasion better and imposing higher penalties. It proposes an alternative approach that places greater emphasis on fostering trust between taxpayers and governments by delivering value to people—in other words, taxpayers derive some benefit in exchange for paying taxes. If being part of the formal economy delivers value to individuals, they will be more inclined to formalize their businesses and pay appropriate taxes.

India’s case

Well-designed digital public infrastructure can help deliver value and thus drive growth in tax collection, India’s experience shows. Digital public infrastructure is an approach to providing services and economic opportunities to citizens by combining interoperable, open-access, and reusable building blocks into a network of digital systems. It can be compared to roads and other physical infrastructure that connect people and give them access to goods and services. Digital public infrastructure combines innovative technology with strong policy frameworks and incentives for private market participation. Data security, privacy, and consent are at its heart.

Individuals and businesses may resist filing taxes because they see it as a costly compliance burden. Staying out of the system—by using cash for informal transactions or not disclosing assets—is often more convenient than joining the formal economy. Digital public infrastructure can turn this thinking on its head and thereby unlock durable increases in tax collection. We identify three steps that can help governments collect more revenue from and broaden the tax base.

First, introduce digitally verifiable assets and credentials that make it less desirable to operate outside the formal economy and tax system. For instance, Aadhaar, in India, provides unique and verifiable digital identification numbers. Among other things, this has enabled individuals and businesses to open bank accounts. It has also reduced public spending by making social benefit payments seamless. Brazil’s Pix, Thailand’s PromptPay, and India’s Unified Payments Interface make digital payments cheap and effortless. And digitally signed documents and certificates, which are independently verifiable by third parties, can make issuing licenses and permits more straightforward.

Second, align incentives for individuals and businesses to join the formal sector. People should see the process of joining the formal sector as generating value for them, first and foremost. For example, by reducing the cost of business verification, digital payment footprints and verifiable business credentials can help individuals and small and medium enterprises gain access to formal credit at competitive rates. In time, the increased volume of payment records will also lead to more transparent tax collection—but this must be a secondary, not a primary, aim. (For example, if a payment network is launched with the explicit objective of linking all transactions on the network to tax reporting, it could discourage businesses and people from using that infrastructure.)

Third, generate value for individuals and businesses through the tax system. The first two steps make it less beneficial for taxpayers to stay out of the formal tax system. However, countries still need to generate value for businesses to engage with the tax filing system, in particular—which can reward compliant filers in various ways:

Give data back to taxpayers. Data is an asset that should be used confidentially and ethically. It should also be given back to taxpayers in a format they trust, so that they can reuse it to access key services. For instance, in India, the tax collection department provides compliant taxpayers with digitally signed (tamper-proof) business IDs they can use as digital know-your-customer credentials. The tax authorities also designed a public verification mechanism to check core business registration facts associated with a goods and services tax (GST) ID number, helping businesses build trust with prospective partners.

Create incentives for filing taxes throughout the supply chain. Regarding India’s GST, the tax department offers businesses an income tax credit discount of up to 20 percent if they purchase goods and services from suppliers also registered and paying tax. This discount applies throughout the supply-chain networks as an incentive for businesses to join the formal tax system. To encourage repeated and timely tax filings, the discount is shared not as cash back but as a credit toward the next tax payment.

Allow the private ecosystem to build seamless filing and value-added services. Opening up use of application programming interfaces (APIs) in the tax system would allow private innovators to build unique digital and physical user experiences for tax filing that combine services and save time for filers. This is a market incentive for private competition based on ease of filing that caters to diverse user needs and drives digitalization. Since the Indian government opened API access, more than 55 licensed third-party platforms have been used to file taxes.

‘Value-first’ lens

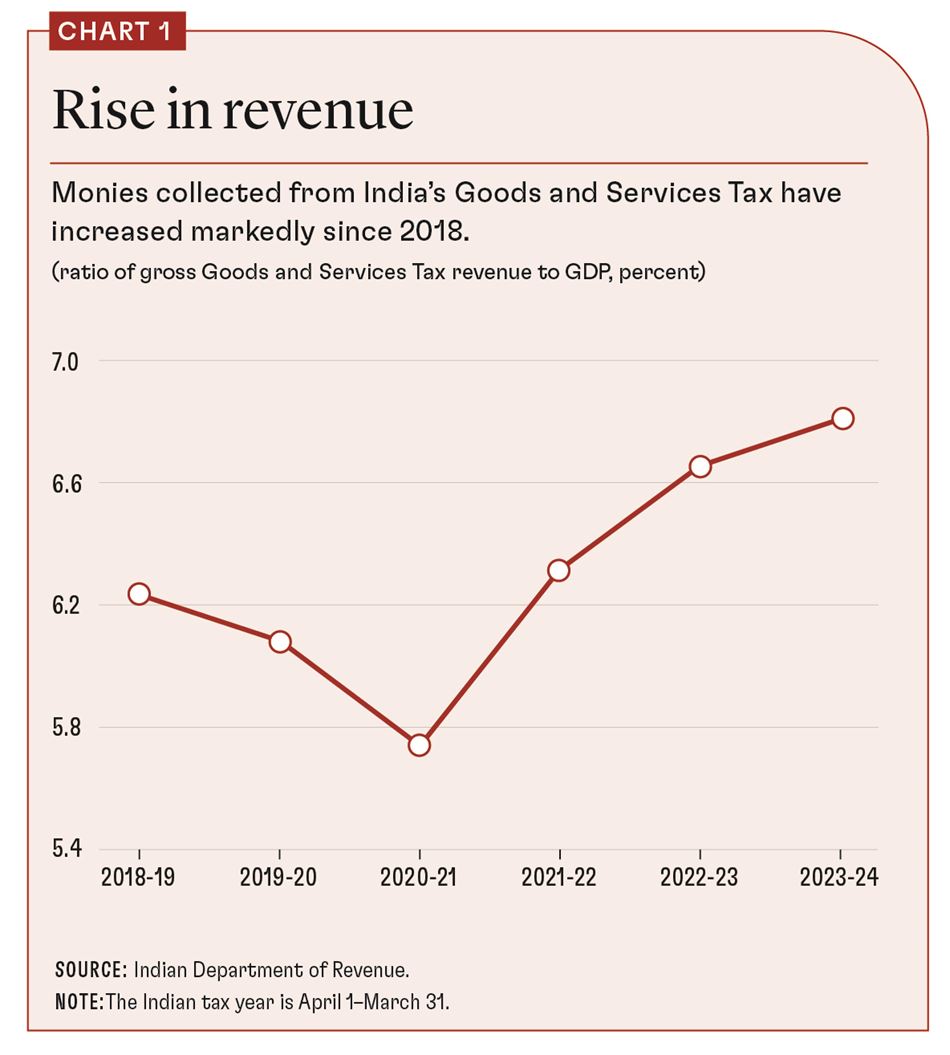

India has successfully leveraged digital public infrastructure—revenue collection via the goods and services tax has grown by more than 50 basis points of GDP since 2018, showing a marked increase over projected collections under the previous tax regime (see Chart 1).

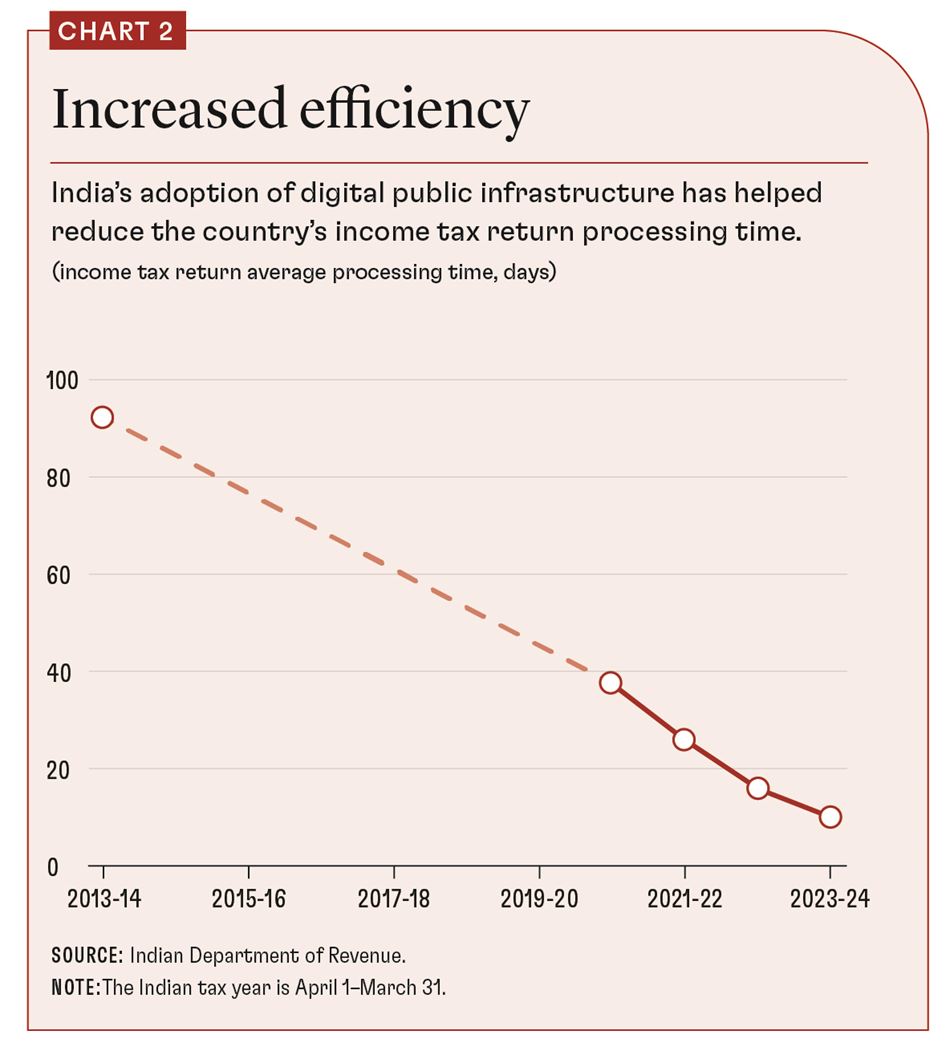

The time it takes to process electronic returns and refunds for taxpayers has fallen significantly (see Chart 2).

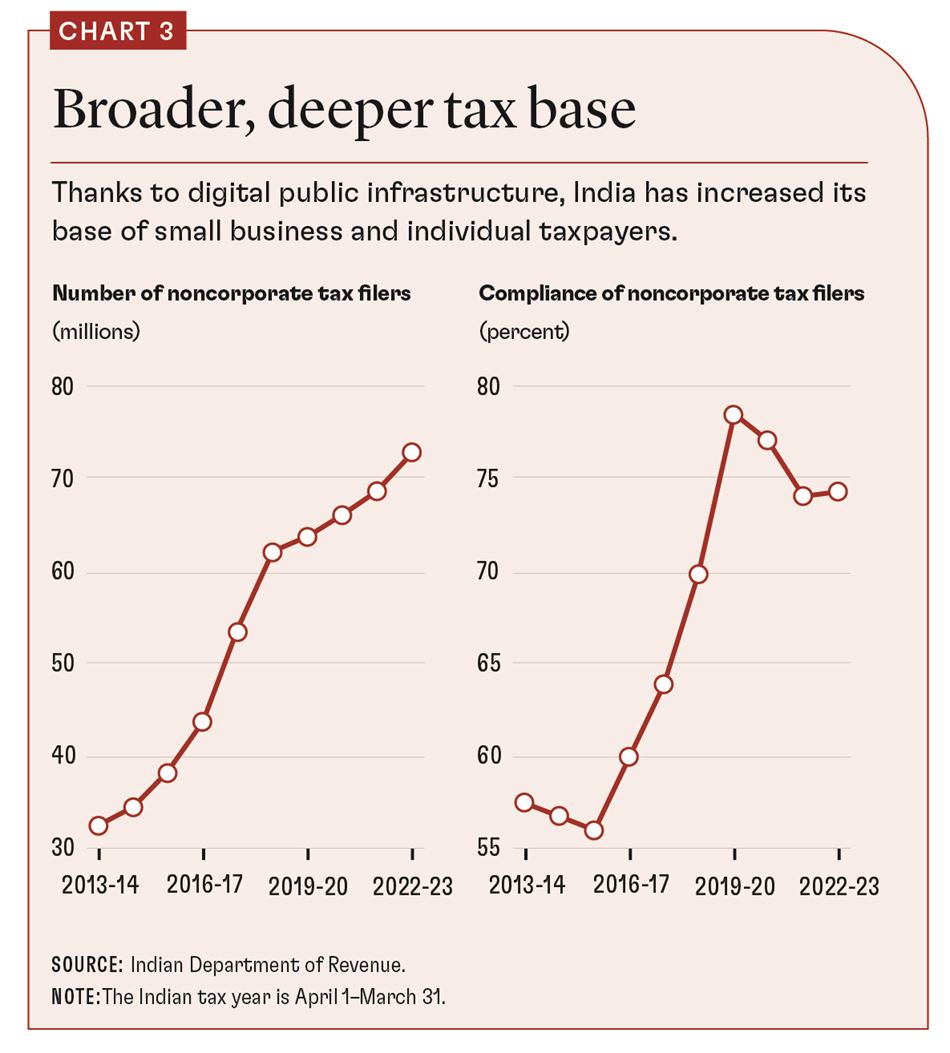

And the tax base has broadened, with a marked and sustained rise in noncorporate taxpayers, including small businesses and individuals (see Chart 3).

A crucial element of India’s digital success is the system’s robust security and privacy controls, which ensure that the government uses taxpayer data confidentially and ethically.

Improvements in revenue collection cannot, however, be attributed to technology alone. Governance and policy reforms are also critical. For instance, India set up the Goods and Services Tax Network as a unified collection mechanism intended to simplify tax compliance and administration for businesses of all sizes.

In summary, sustainable increases in revenue mobilization result when governments’ systems and processes provide value to people and businesses, and tax collection increases gradually over time as a derivative benefit. As digital transactions become an integral part of business and life, it is more difficult for people to evade the system. Moving from an enforcement-of-collection lens to a value-first lens is a promising new way to drive lasting increases in revenue collection and encourage a more trusted social contract between individuals and the government.

Trust and Taxation

Trust in government and government effectiveness have a reciprocal relationship. Trust is enhanced when political institutions are strong and governments implement policies and initiatives that are aligned with the public interest and improve people’s daily lives. And governments can be effective only when their citizens trust them enough to comply with laws, thereby creating the space for reforms.

Of course, trust in government needs more than just robust digital platforms. But the building of India’s digital platform infrastructure has laid some of the foundations for increasing trust by creating an inclusive platform for citizens to transact digitally and empowering users to have more control over their data. Good digital infrastructure can create trust between any two counterpart actors by introducing tamper-proof components for identity, payments, and security, which allows citizens and businesses to be certain of the identity of their counterpart and of the legitimacy of the transaction. This allows the reduction in explicit and implicit costs to citizens when they interact with their government, and for businesses in their transactions with individuals, other businesses, and the government.

Trust can also be built in the overall system through other channels, such as the reliability of its functioning or swift and transparent dispute resolution. Countries need to make sustained progress in strengthening digital systems as well as broader policy and institutional frameworks to strengthen trust between citizens and the state. In turn, this will increase confidence in the economy and boost investment, innovation, productivity—and ultimately growth.

Kalpana Kochhar and Sanjay Jain of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation contributed to this article.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.