Published on April 7, 2022

The Future of Inflation Part II: The second article in our three-part series examines the trade-offs from inflation

“News about inflation seems to have serious consequences for approval ratings of presidents and for outcomes of elections. Public-opinion polls have shown that inflation (or something like inflation) has often been viewed as the most important national problem.” So wrote Nobel laureate Robert Shiller (1997). Today, public concerns about the resurgence of inflation in large parts of the world show that people remain fearful of it. Yet while households have a strong aversion to inflation, in standard neoclassical models the welfare costs are small. Given this disconnect, and to help inform the debate, we provide a review of the costs and benefits of inflation and assess the trade-offs.

Inflation costs

Any discussion of inflation costs must confront the gap between the harm of inflation in neoclassical macroeconomic theory models (theoretical harm) and the harm that people perceive. Since economic models tend to suggest low levels of theoretical harm, from a neoclassical perspective, Shiller’s findings that people strongly dislike inflation are about the harm that people perceive but that isn’t really there in their models. In other words, inflation would be no big deal if we humans were neoclassical creatures, but we aren't.

Thus, economists and policymakers are left with three choices. One, policymakers will have to address a dislike of inflation even if they believe it is unfounded and that the main cost of inflation stems from the damage of believing in an imaginary harm. A second option is to incorporate special features into theoretical models to raise the cost of inflation. And a third is to accept that we are not neoclassical creatures, and that the perceived harm is a real and sizable cost for humans. In line with this discussion, we provide a quick summary of the theoretical literature on the costs of inflation, but then focus on the cognitive costs, including both sentiment and perceptions and pragmatically costly confusion.

Economists have focused mainly on three potential costs of inflation, but typically find small or moderate welfare costs for each (our focus is on the costs of single-digit inflation, and we are not considering infrequent cases of hyperinflation—which does however generate long-lasting memories and could contribute to inflation aversion):

- Shoe-leather costs, the main neoclassical cost of inflation: These are incurred by more frequent trips to the bank—since people prefer holding smaller cash balances to avoid the “inflation tax.” To minimize such a tax, Milton Friedman (1969) suggested a monetary policy rule that makes the nominal interest rate equal to zero. Building on the work of Robert Lucas (2000), Peter Ireland (2009) estimates that such costs are small and amount to only 0.05 percent of annual income for 2 percent inflation. However, in the presence of market power (of firms or banks) this welfare cost can be somewhat higher (Lagos and Wright 2005; Kurlat 2019).

- Misallocation of resources and menu costs: Price stickiness at the firm level can cause resources to be misallocated by moving relative prices away from what they should be because price changes are too infrequent. Price stickiness may arise due to menu costs—an idea introduced by Greg Mankiw (1985) and George Akerlof and Janet Yellen (1985)—incurred when businesses change their prices (such stickiness may reflect the aversion to or cognitive cost of inflation faced by consumers or information processing costs). These costs, while relatively small, may be greater when inflation is higher.

- Unpredictability: Friedman (1977) stressed the association between higher inflation and inflation uncertainty, which can produce harmful distortions and possibly arbitrary redistribution.

Cognitive costs (confusion and sentiment) may be the most serious cost of inflation. These arise both from the confusion of living in a world beset by inflation and the feelings that perceived inflation generate. It is traditional in economic models to assume that people are infinitely intelligent when it comes to making economic decisions—and that anything that takes just a little math to correct is therefore costless—but in the real world, information processing is costly, and confusion engendered by inflation can be a serious cost, though one that is difficult to quantify precisely.

As Mankiw (2016) writes, “Imagine that we took a poll and asked people the following question: ‘This year the yard is 36 inches. How long do you think it should be next year?’ Assuming we could get people to take us seriously, they would tell us that the yard should stay the same length—36 inches. Anything else would complicate life needlessly.”

Some examples of confusion costs include people blaming “inflation” for real wages lower than they would like, unintended distortions in the tax code, and people mistaking nominal for real rates of return in their retirement planning. Further, the perception of inflation can generate strong negative sentiments. In his survey, Shiller (1997) found that the public’s main perceived cost of inflation is that it hurts their standard of living. In the survey, this worry was amplified when respondents believed that some badly behaving or greedy people caused prices to increase and that these increases were not met with a rise in wages.

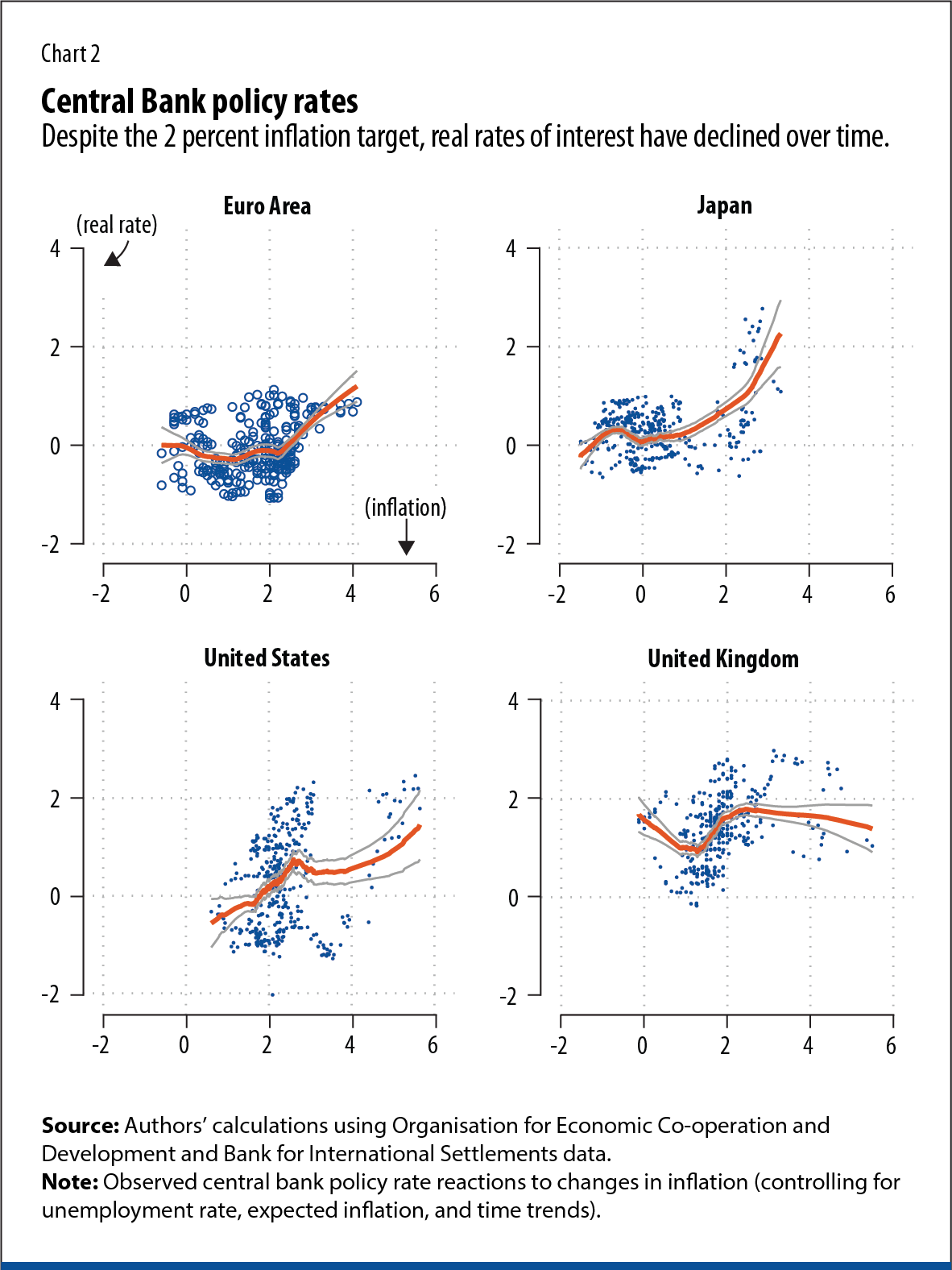

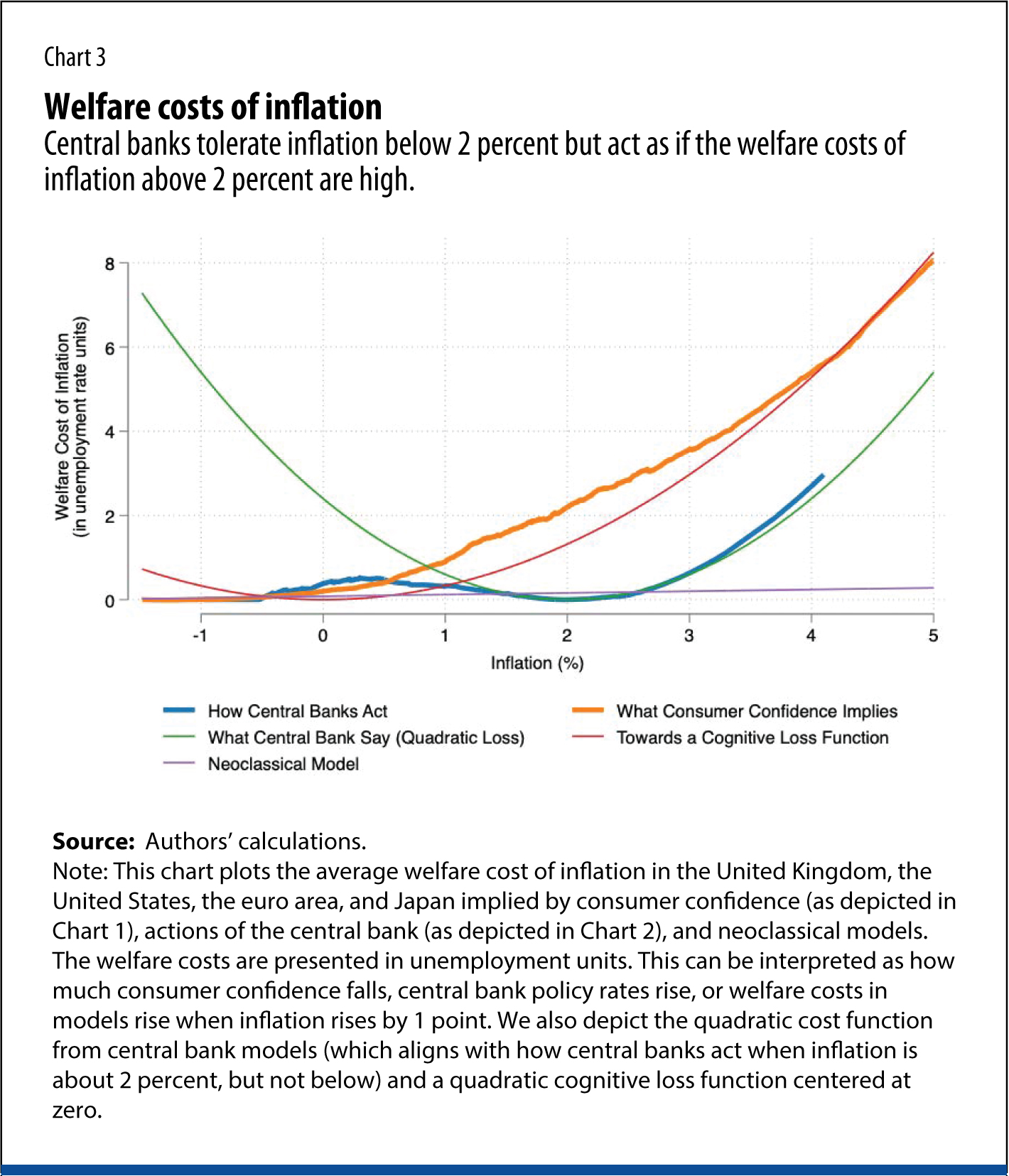

To measure such cognitive costs of inflation, we compare consumer confidence between 1980 and 2021 across six major economies (for which comparable Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development data are available—Chart 1). The exercise yields three insights. First, across all countries, higher inflation is associated with lower consumer confidence. Second, the size of the impact is large, even when inflation is close to zero. At zero, a 1 percentage point increase in inflation is associated with the same impact on confidence as a 1 percentage point increase in unemployment. And third, the adverse impact is greater at higher levels of inflation, well captured by a quadratic function centered at just below zero inflation (Chart 3, discussed below). Overall, even low levels of inflation are perceived as bad and much costlier than what neoclassical models typically suggest.

Inflation benefits

From our perspective, moderate inflation has two main benefits, which together are the primary reason key central banks have settled on an inflation target of 2 percent.

First, reduced risk of hitting the zero lower bound: The conventional argument against setting a zero or negative inflation target is that it would lead to a higher risk of hitting the zero lower bound, severely restricting the firepower of central banks. This would happen because of a decline in inflation expectations and thus nominal interest rates.

This view was recently echoed by Paul Krugman (2022), who wrote that in the late 1980s a “significant number of economists and, perhaps even more so, central bankers wanted true price stability: zero inflation. On the other hand, some economists were worried, even then, about the zero lower bound. For example, in 1991 Larry Summers worried that with zero inflation the central bank might find itself unable to cut rates enough to ward off a recession.”

Thus, while conventional monetary policy models predict that the optimal inflation target is zero (see Woodford 2003), central banks in many advanced economies have officially adopted a 2 percent inflation target.

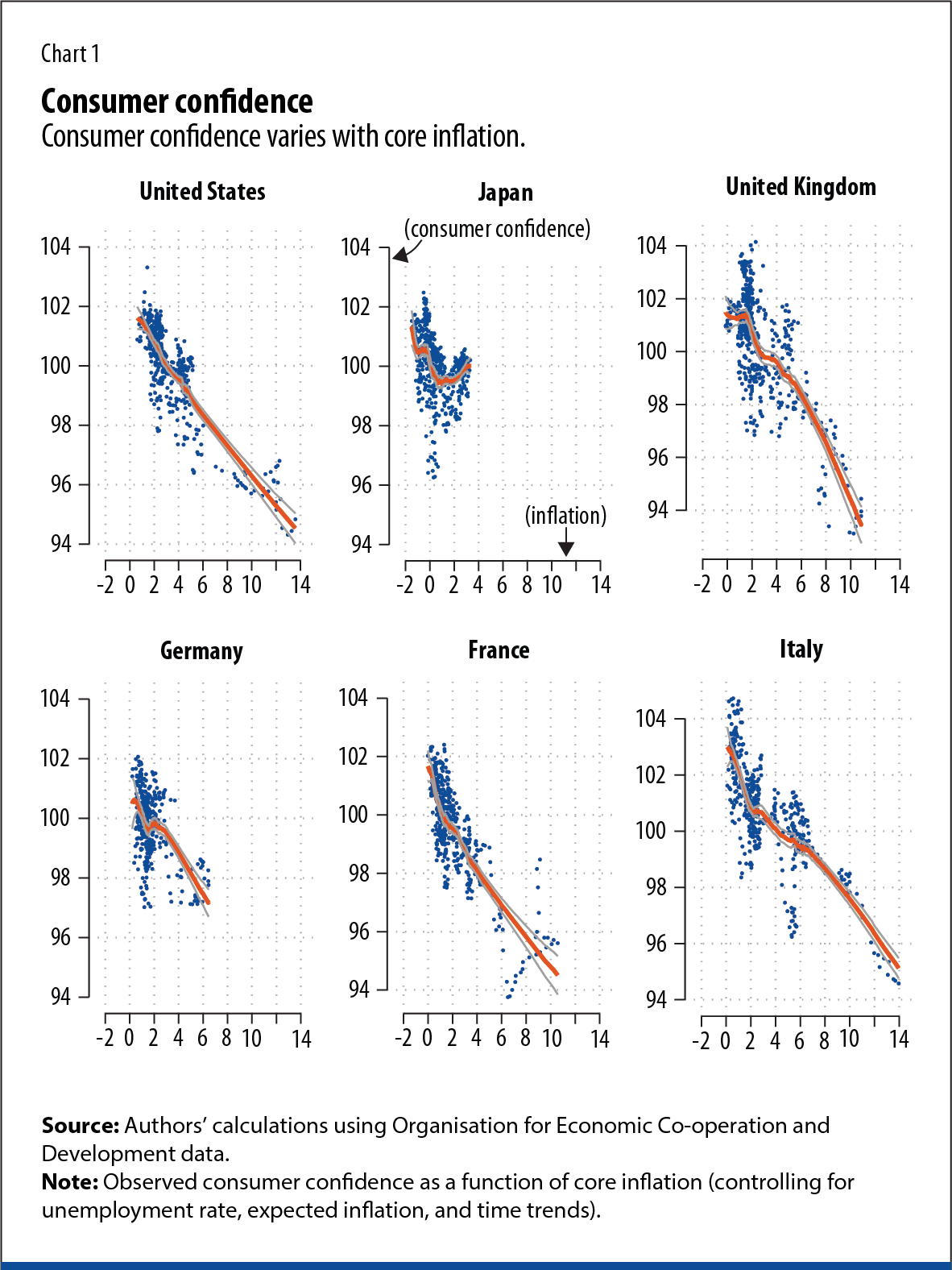

In practice, however, despite central banks adopting the 2 percent target, real rates of interest have declined over time, with central banks facing the zero lower bound (or the effective lower bound when they implement mild negative rates) for several years in recent decades (Chart 2). A consequence of the zero lower bound is an actual response of central banks highly asymmetric above and below the 2 percent target—with central banks tolerating inflation below 2 percent but acting as if the welfare costs of inflation above 2 percent are high (Chart 3).

Second, overcoming downward wage stickiness: Sticky wages occur when earnings don’t sufficiently adjust to changes in labor market conditions. While wages gravitate toward stickiness in both directions, firms tend to find it harder to cut wages than raise them. The real reasons for downward wage stickiness are not well understood. Stickiness is prevalent even in the absence of unions.

Truman Bewley (1999), based on hundreds of interviews, concluded that pay cuts may hurt worker morale even more than layoffs. From this perspective, higher inflation may make it easier for firms to cut real wages without workers fully realizing and resisting it—due to nominal confusion. This insight can be traced to Keynes (1936), who wrote, “It would be impractical to resist every reduction in real wages, due to a change in the purchasing-power of money which affects all workers alike.” While such reductions in real wages may be a cost in various settings, it may be a benefit in some cases when there is large misalignment between the marginal product of labor and wages.

In addition, there may be two medium-sized benefits of positive inflation: financial stability benefits and antitrust benefits. First, higher inflation—thereby leading to higher nominal rates—may make it harder for Ponzi schemes, irrational bubbles, and zombie firms to prosper. This is because lower nominal interest rates may make it harder to detect the true creditworthiness of borrowers. For example, the monthly loan payment relative to a borrower’s income falls when the nominal interest rate falls, making it easier for firms to hide deterioration in their net worth. Second, there may be a political economy effect: higher inflation encourages politicians to institute more price-lowering deregulation (as US President Jimmy Carter did in the 1970s with air travel and trucking) and more price-lowering antitrust efforts (something the Biden administration has been moving toward recently).

Ponzi schemes and irrational bubbles can be fixed by raising expectations of payback rates (which have only a traditional connection—and no necessary connection—to nominal interest rates and inflation). And we hope there are ways to encourage policymakers to conduct more price-lowering deregulation and price-lowering antitrust efforts rather than relying on high inflation.

Finally, although higher inflation may help combat some debt overhang, use of this tool is likely to raise the risk premium on future debt as expectations of possible use of inflation to fight debt overhang increase. Moreover, the net welfare benefits of such an ”inflation tax” may be relatively small in most circumstances—since the reduction in real debt is a transfer from creditors to debtors with an equal and opposite wealth effect. That is, while higher unexpected inflation may lower the real debt burden for borrowers, it simultaneously reduces the real net wealth of lenders. To the extent there are distributional benefits of such wealth transfers, we consider it better to pursue those through deliberate fiscal policy; higher inflation may be a costly way to transfer wealth and is badly targeted because it depends on debt rather than directly on poverty.

Fundamental trade-off

The fundamental trade-off for inflation is by and large about weighing the cognitive costs to households against the two macroeconomic benefits of higher inflation—less risk of hitting the zero lower bound and avoiding problems from downward wage stickiness. Inflation is a bad in many ways, but policymakers tolerate it because it offers them two benefits. In particular, the zero lower bound benefit of positive inflation is internalized by the central bank, but not by ordinary households. This gap has spawned a situation in which central banks tolerate and target 2 percent annual inflation permanently, despite households feeling a high cost of inflation even at those levels (this gap is depicted in Chart 3). The 2 percent number is not special in itself; it is relevant only because advanced economy central banks have decided to settle on it to operationalize ”price stability.”

But do we need to accept this trade-off? There are two possible scenarios going forward. In the first, we maintain the status quo with no change in the fundamental trade-off. On this path, the world will alternate between (a) long periods of sluggish growth at the zero lower bound but inflation below 2 percent and (b) periods of normal growth away from the zero lower bound but with cognitively costly average inflation of 2 percent (with occasional spikes even higher from a base of 2 percent).

In the second scenario, there is wider recognition that the zero lower bound and wage stickiness are not laws of nature. The first is a policy choice, and the second is an evolving norm. Spurred by this recognition, innovation in the real-world macroeconomic toolkit will allow us to break the zero lower bound and the move toward a modern “share economy” with flexible labor markets.

In this context, there are now various options available to central banks to break through the zero lower bound (Agarwal, Kimball 2015; Agarwal, Kimball, 2019). In “The Share Economy,” Martin Weitzman (1986) laid out the foundation for how a transition to paying workers more of their compensation in the form of annual bonuses can help overcome wage stickiness (because it is easier to adjust bonuses than regular monthly wages). A New York Times editorial called Weitzman’s proposal the “best idea since Keynes”; Larry Summers called it the “most significant contribution to macroeconomics that has occurred in the 1980s.” With the rise in modern work practices—such as teleworking and the gig economy—and fast-evolving norms in labor markets, Weitzman’s proposal is due for a revival.

The speed at which we converge to the second scenario will depend on the collective creativity of macroeconomists and practitioners. We predict that as innovation in macroeconomics expands the toolkit and opens new avenues, the benefits of positive inflation will fade, and the future of inflation will tend toward zero.

Podcast

Most people and virtually all businesses now use electronic money for their transactions, yet central banks are still dealing with....

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.

References:

Agarwal, R., M. Kimball. 2015. “Breaking through the Zero Lower Bound.” IMF Working Paper 15/224, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

Agarwal, R., M. Kimball. 2019. “Enabling Deep Negative Rates to Fight Recessions: A Guide.” IMF Working Paper 19/84, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

Ireland, P. N. 2009. “On the Welfare Cost of Inflation and the Recent Behavior of Money Demand. American Economic Review 99 (3): 1040–52.

Shiller, R. J. 1997. “Why Do People Dislike Inflation? In Reducing Inflation: Motivation and Strategy, 13–70. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Weitzman, M. L. 1986. The Share Economy: Conquering Stagflation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.