The Middle East and Central Asia face a sobering climate reality. Temperatures have risen twice as fast as the global average, and rainfall has become scarcer and less predictable. Fragile states are disproportionally affected and conflicts may worsen. The toll this is taking on people and economies is poised to worsen.

This week’s United Nations Climate Change Conference, or COP28, provides a forum to discuss the policies needed to stave off more disruptive climate change. It comes at a vital time: our new analysis shows current global commitments would reduce emissions by just 11 percent by the end of this decade, well short of the 25 percent to 50 percent that’s needed to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement. All countries must step up.

Devasting impact, economic disruption

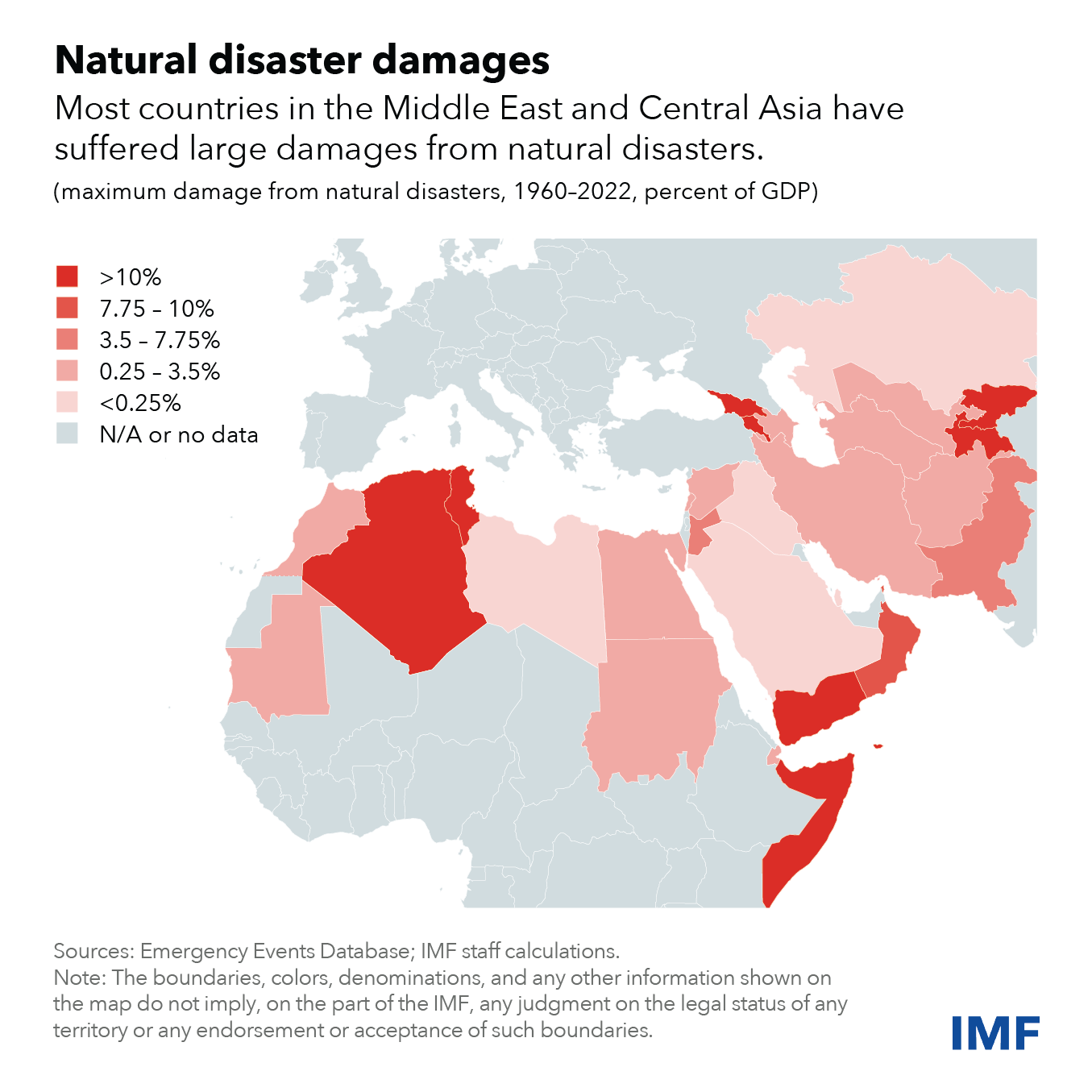

From devasting floods in Libya and Pakistan to drought in Somalia, the far-reaching impact of climate change is obvious. Record temperatures amid scorching heatwaves are becoming a new normal. Droughts leave farmland parched and rivers depleted. Violent storms batter coastal areas.

In addition to the human toll, climate change has huge economic and social costs. Over the past three decades, changing temperature and rainfall patterns have eroded per capita incomes and significantly altered the sectoral composition of output and employment. We see this pattern emerging in all corners of the world, but it is especially true for countries in the Middle East and Central Asia.

A recent IMF study shows the fundamental economic disruptions brought about by climate change not only endanger food security but also undermine public health, with a ripple effect on poverty and inequality, displacement, political stability and even conflict. Past climate disasters have resulted in permanent gross domestic product losses of 5.5 percent in Central Asia and 1.1 percent in the Middle East and North Africa. And these disasters will only become more frequent.

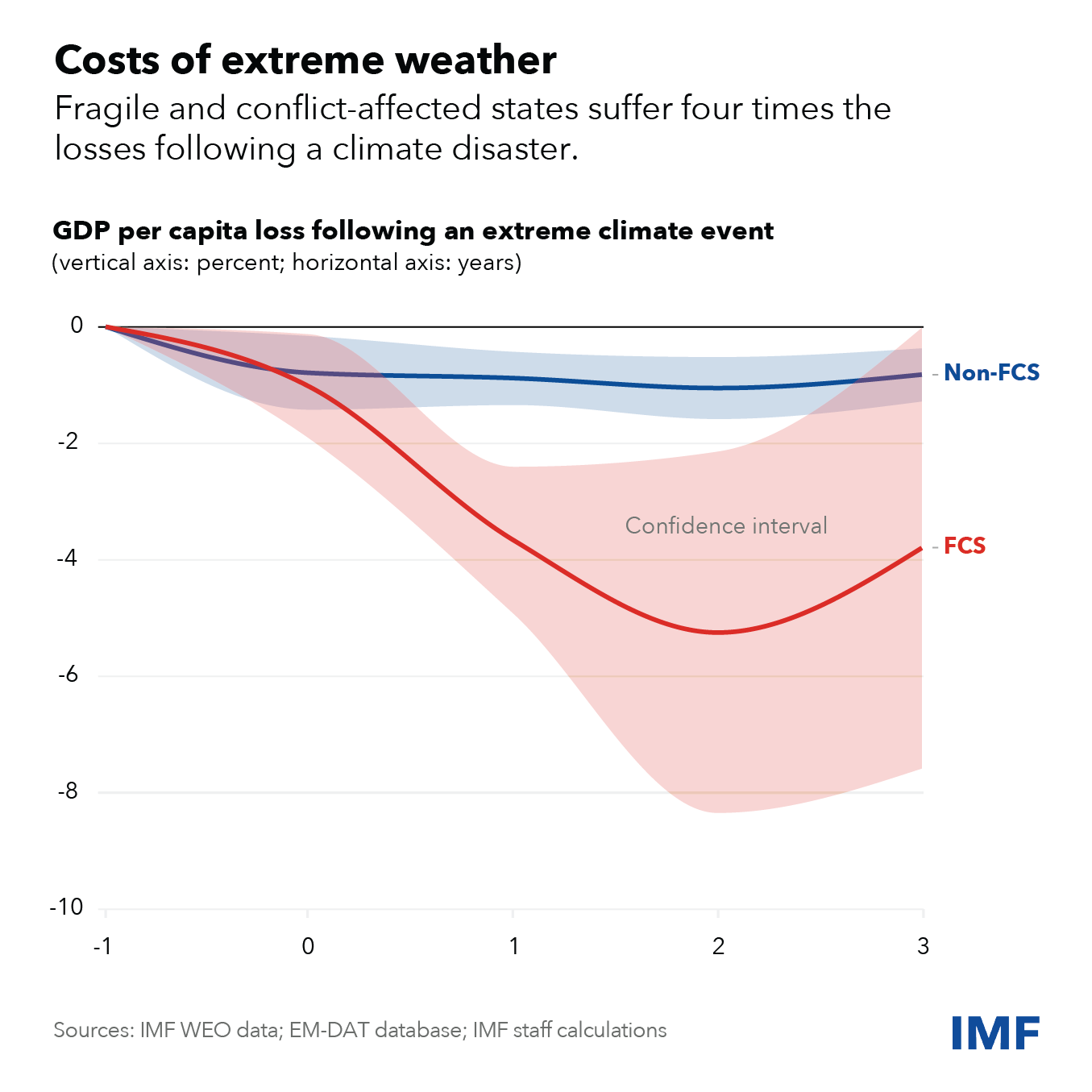

Climate effects are particularly pronounced in fragile and conflict-affected states. They suffer four times higher output losses after climate-related weather shocks, compounding their existing fragility.

Climate displacement crises, such as in Somalia, demonstrate the destructive consequences and human toll of climate change, especially for vulnerable countries and regions. Climate change can even make conflicts deadlier.

Policy priorities

Frontloading action on climate change is a must. So, governments in the Middle East and Central Asia must step up their goals both to adapt to climate change and to reduce their own contribution to global warming. Investment of up to 4 percent of GDP annually is needed to sufficiently boost climate resilience and meet 2030 emissions reduction targets, according to recent IMF studies on adaptation and mitigation.

Amid higher borrowing costs and already constrained government spending powers, attracting more private finance is crucial to bridge the financing gaps. Measures such as accelerated fuel-subsidy reform and carbon taxes, and other climate regulations could also help ease the funding burdens and give investors clearer signals.

The good news is that many countries in the Middle East and Central Asia are already taking steps to alleviate the devastating impacts of climate change. For instance, Morocco, Jordan, and Tunisia have improved water management practices, helping to enhance their resilience amid prolonged droughts.

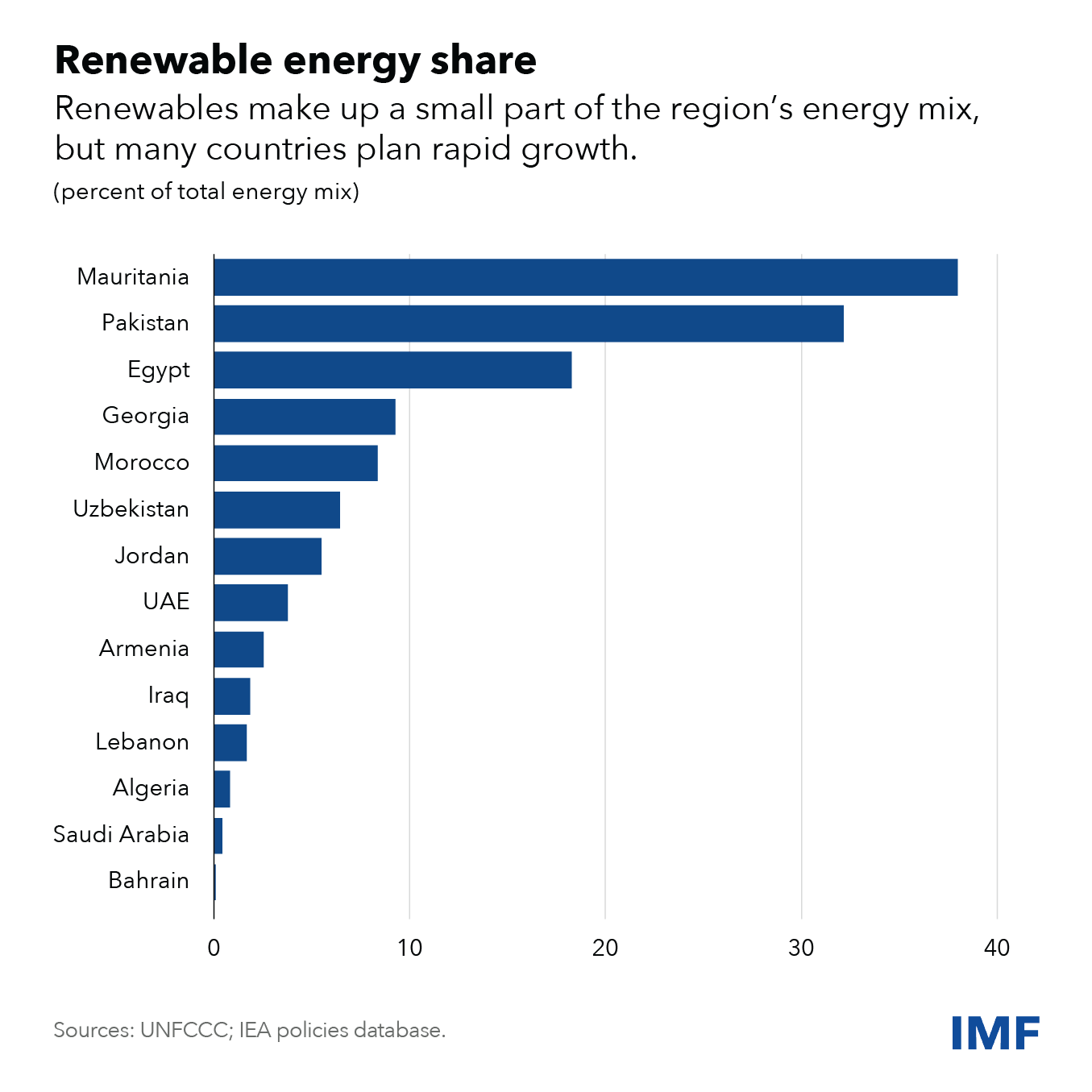

Countries also are gearing up to contain their carbon footprint, from fossil-fuel subsidy reforms in Jordan to solar power projects in the United Arab Emirates and Qatar.

IMF research sheds light on fiscal policies that can help countries in the region achieve their climate pledges by cutting per capita greenhouse gas emissions by up to 7 percent by 2030 and accelerate policies further to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050.

However, much more ambitious climate action is needed in the Middle East and Central Asia. Both the adaptation and mitigation policies currently in place must be expanded and reinforced. Nations must prioritize comprehensive strategies that not only address the immediate crises but also prepare for the longer-term consequences of climate change. Policymakers should prioritize investment in “no regret” measures such as climate-resilient infrastructure and agriculture, disaster risk management, and social protection.

Managing trade-offs

The policy options, however, often require economic tradeoffs. Reducing fuel subsidies or putting a price on carbon emission, for example, promise long-term gains but may raise transition costs in the near term due to large shifts in economic behavior.

Boosting investment in renewable energy through additional government spending and subsidies—such as the development of the world’s largest solar power plant in Saudi Arabia, led by its sovereign wealth fund—might seem easier in the near term. Yet, it would make the energy transition more costly overall, as it won’t deliver the economic efficiency resulting from carbon pricing. For these reasons, policymakers should find a mix of policies to balance these trade-offs.

Ultimately, more action also requires more multilateral support. It can help spark action where it is needed most, transfer valuable technical knowledge and policy experiences, and catalyze other funding sources to meet the region’s large adaptation and mitigation climate financing needs—all particularly important for low- and lower-middle income countries.

The IMF’s Resilience and Sustainability Facility will help address climate vulnerabilities. An example in the region is the recent $1.3 billion RSF climate program with Morocco.

Yet the scale of the challenge means that global and regional initiatives such as COP28 remain instrumental to foster cross-border collaboration and promote private sector climate finance. This should include securing additional climate funding for the most vulnerable countries.