Policymakers may need to react by pulling multiple policy levers, depending on Fed actions and their own challenges at home.

For most of last year, investors priced in a temporary rise in inflation in the United States given the unsteady economic recovery and a slow unravelling of supply bottlenecks.

Now sentiment has shifted. Prices are rising at the fastest pace in almost four decades and the tight labor market has started to feed into wage increases. The new Omicron variant has raised additional concerns of supply-side pressures on inflation. The Federal Reserve referred to inflation developments as a key factor in its decision last month to accelerate the tapering of asset purchases.

These changes have made the outlook for emerging markets more uncertain. These countries also are confronting elevated inflation and substantially higher public debt. Average gross government debt in emerging markets is up by almost 10 percentage points since 2019 reaching an estimated 64 percent of GDP by end 2021, with large variations across countries. But, in contrast to the United States, their economic recovery and labor markets are less robust. While dollar borrowing costs remain low for many, concerns about domestic inflation and stable foreign funding led several emerging markets last year, including Brazil, Russia, and South Africa, to start raising interest rates.

New risks to recovery

We continue to expect robust US growth. Inflation will likely moderate later this year as supply disruptions ease and fiscal contraction weighs on demand. The Fed’s policy guidance that it would raise borrowing costs more quickly did not cause a substantial market reassessment of the economic outlook. Should policy rates rise and inflation moderate as expected, history shows that the effects for emerging markets are likely benign if tightening is gradual, well telegraphed, and in response to a strengthening recovery. Emerging-market currencies may still depreciate, but foreign demand would offset the impact from rising financing costs.

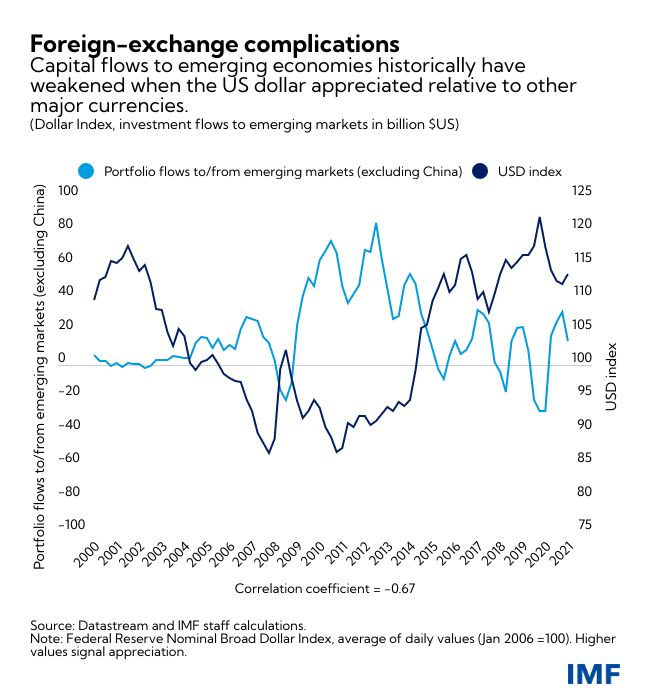

Even so, spillovers to emerging markets could also be less benign. Broad-based US wage inflation or sustained supply bottlenecks could boost prices more than anticipated and fuel expectations for more rapid inflation. Faster Fed rate increases in response could rattle financial markets and tighten financial conditions globally. These developments could come with a slowing of US demand and trade and may lead to capital outflows and currency depreciation in emerging markets.

The impact of Fed tightening in a scenario like that could be more severe for vulnerable countries. In recent months, emerging markets with high public and private debt, foreign exchange exposures, and lower current-account balances saw already larger movements of their currencies relative to the US dollar. The combination of slower growth and elevated vulnerabilities could create adverse feedback loops for such economies, as the IMF highlighted in its October releases of the World Economic Outlook and Global Financial Stability Report.

Difficult tradeoffs

Some emerging markets have already started to adjust monetary policy and are preparing to scale back fiscal support to address rising debt and inflation. In response to tighter funding conditions, emerging markets should tailor their response based on their circumstances and vulnerabilities. Those with policy credibility on containing inflation can tighten monetary policy more gradually, while others with stronger inflation pressures or weaker institutions must act swiftly and comprehensively. In either case, responses should include letting currencies depreciate and raising benchmark interest rates. If faced with disorderly conditions in foreign exchange markets, central banks with sufficient reserves can intervene provided this intervention does not substitute for warranted macroeconomic adjustment.

Nevertheless, such actions can pose difficult choices for emerging markets as they trade off supporting a weak domestic economy with safeguarding price and external stability. Similarly, extending support to businesses beyond existing measures may increase credit risks and weaken the longer-term health of financial institutions by delaying the recognition of losses. And rolling back those measures could further tighten financial conditions, weakening the recovery.

To manage these tradeoffs, emerging markets can take steps now to strengthen policy frameworks and reduce vulnerabilities. For central banks tightening to contain inflation pressures, clear and consistent communication of policy plans can enhance the public’s understanding of the need to pursue price stability. Countries with high levels of debt denominated in foreign currencies should look to reduce those mismatches and hedge their exposures where feasible. And to reduce rollover risks, the maturity of obligations should be extended even if it increases costs. Heavily indebted countries may also need to start fiscal adjustment sooner and faster.

Continued financial policy support for businesses should be reviewed, and plans to normalize such support should be calibrated carefully to the outlook and to preserve financial stability. For countries where corporate debt and bad loans were high even before the pandemic, some weaker banks and nonbank lenders may face solvency concerns if financing becomes difficult. Resolution regimes should be readied.

Commitments and confidence

Beyond these immediate measures, fiscal policy can help build resilience to shocks. Setting a credible commitment to a medium-term fiscal strategy would help boost investor confidence and regain room for fiscal support in a downturn. Such a strategy could include announcing a comprehensive plan to gradually increase tax revenues, improve spending efficiency, or implement structural fiscal reforms such as pension and subsidy overhauls (as described in the IMF’s October Fiscal Monitor).

Finally, despite the expected economic recovery, some countries may need to rely on the global financial safety net. That may include using swap lines, regional financing arrangements, and multilateral resources. The IMF has contributed with last year’s $650 billion allocation of Special Drawing Rights, the most ever.

While such resources boost buffers against potential economic downturns, past episodes have shown that some countries may need additional financial breathing room. That’s why the IMF has adapted its financial lending toolkit for member nations. Countries with strong policies can tap precautionary credit lines to help prevent crises. Others can access lending tailored to their income level, though programs must be anchored by sustainable policies that restore economic stability and foster sustainable growth.

While the global recovery is projected to continue this year and next, risks to growth remain elevated by the stubbornly resurgent pandemic. Given the risk that this could coincide with faster Fed tightening, emerging economies should prepare for potential bouts of economic turbulence.