March 20, 2018

[caption id="attachment_22989" align="alignnone" width="1024"] When governments subsidize private investment in adaptation, the economic costs of extreme weather events can be reduced (photo: Leolintang/iStock by Getty Images).[/caption]

When governments subsidize private investment in adaptation, the economic costs of extreme weather events can be reduced (photo: Leolintang/iStock by Getty Images).[/caption]

Climate change is one of the greatest threats facing our planet. Its negative effects on health, the biosphere, and labor productivity are already being felt throughout the world. Aware of the danger, communities, households, and governments have started taking measures to reduce their exposures and vulnerability to weather shocks and climate change. Our study in the World Economic Outlook shows that public investment in adaptation can partially reduce the economic costs of severe weather events.

Government involvement is key

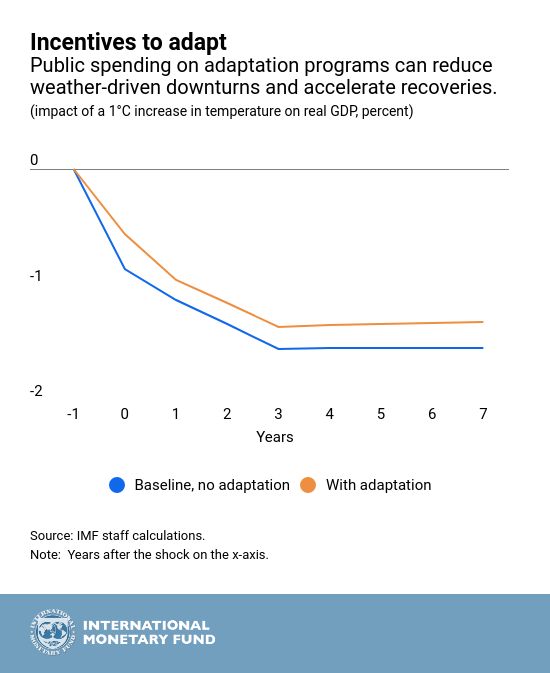

In our previous blog, we used historial evidence to show how a 1°C increase in temperature in a country with an average annual temperature of 25°C, such as Bangladesh, Haiti, and Gabon, would reduce per capita output by 1.5 percent—a loss that persists for at least 7 years. What would the benefits be if governments provided incentives for investing in adaptation to climate change? Our model simulations suggest that the benefits can be significant.

Households and firms already invest in adaptation to reduce the impact of changing weather conditions—for example, by planting more heat-resistant crops or investing in green infrastructure. But the benefits of many adaptation measures do not accrue solely to those who make the investment. For example, an early-warning system for extreme weather will be enjoyed freely by everyone living in the area.

Because households and firms do not take into account the full social benefits of these investments, governments will need to step in. Using a dynamic general equilibrium model, we show that if governments subsidize private investment in adaptation, the economic burden of weather shocks could be partially reduced.

Moreover, due to the smaller damage to output, the reduced losses from weather shocks as a result of investing in adaptation measures could significantly exceed the cost to the public coffers over time.

Our model simulation illustrates a general principle that governments should support adaptation to improve resilience and reduce the impact of weather-related shocks. Many governments have already started implementing strategies to bolster climate change adaptation. And there have been successes.

Social safety nets in Ethiopia

In 2006, the Ethiopian government and international partners established the Productive Safety Net Program. The program provides cash and food to families that are unable to feed themselves due to droughts, delayed rains, and flooding that threaten food security. The aid is contingent on participation in local productivity-enhancing or environmental programs—for example, land rehabilitation, improvement of water sources, and construction of infrastructure such as roads and hospitals.

Program beneficiaries experience a 25 percent smaller drop in consumption after droughts relative to those not in the program. The program has also reduced soil loss by more than 40 percent, improved availability of water, and increased land productivity.

Climate-smart infrastructure in Malaysia

The Stormwater Management and Road Tunnel (SMART Tunnel) in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, serves a dual purpose: it carries traffic and helps combat flash floods. The tunnel consists of three levels. Normally, the top two levels carry road traffic. However, they can be temporarily used as storm drains. At a cost of about $500 million, the SMART Tunnel is expected to prevent more than $1.5 billion in flood damage and reduce the costs of traffic congestion by more than $1 billion over the next 30 years.

Centralized air conditioning in India

High temperatures reduce labor productivity and can also harm health. Air-conditioning is the most common solution to deal with excessive heat. However, the negative effects of air-conditioning, such as increased energy consumption and pollution, cannot be ignored. Moreover, high up-front costs and infrastructure requirements push air conditioning out of reach for poor and vulnerable populations, especially in low-income countries.

District cooling, a centralized air-conditioning system where centrally chilled water is distributed to consumers through underground pipes, can reduce these negative effects. It is in use in several major cities in advanced economies and is currently under construction by the Government of Gujarat, India, in the Gujarat International Finance Tec-City. Centralized cooling systems reduce cost and pollution by consuming 35 to 50 percent less energy than individual air cooling units. These systems unburden the electricity sector and make indoor climate control more accessible by eliminating the up-front cost for its users.

Averting the crisis

Climate change adaptation can lessen the economic costs of climate change, as illustrated by our model simulation and various examples around the world. But investing in successful adaptation strategies is expensive. It will further stretch the budgets of already very poor countries, where the adverse effects of climate change are most pronounced.

Hence, it is imperative that the international community, particularly the advanced economies, which have emitted the lion’s share of greenhouse gasses, help finance adaptation related projects in poorer countries.

That said, adaptation alone is not enough. The only long-term solution for the climate change crisis is to sharply reduce the greenhouse gas emissions responsible for Earth’s warming.