Good economics demands that we manage Nature better

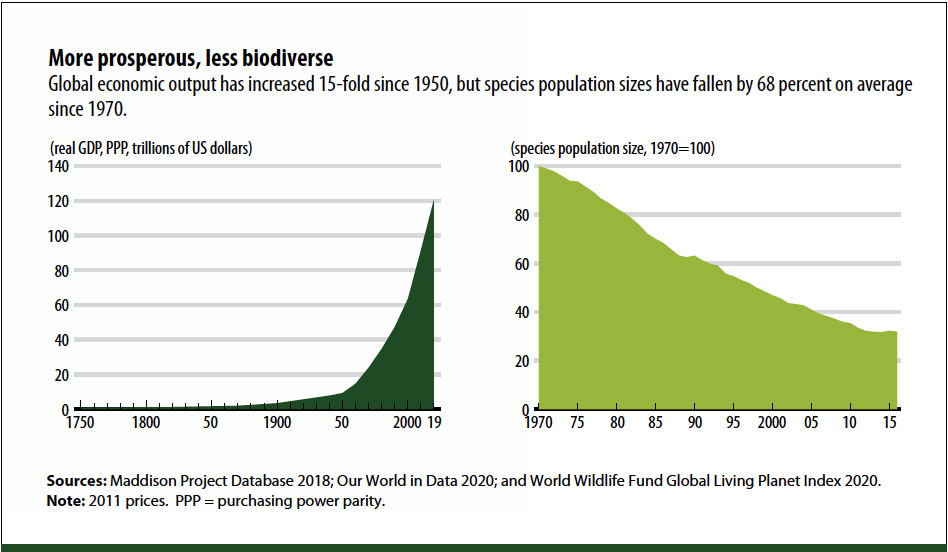

The past 70 years are a success story on many counts. We are healthier, live longer, and enjoy higher income, on average, than our predecessors. The proportion of the world’s population in absolute poverty has fallen dramatically. As we benefit from advances in technology, modern science, and food production, we may be excused for thinking that humanity never had it so good. Global GDP has risen enormously since the 1950s (see chart), and world economic output is 15 times higher.

These achievements conceal a simple truth, however, which has profound consequences not only for how we think about and practice economics, but also for the way we live our lives. All the prosperity we have enjoyed relies on the Nature that surrounds us and of which we are a part—from the food we eat, to the air we breathe, to the decomposition of our waste, to opportunities for recreation and spiritual fulfilment. Yet the biosphere has diminished during that same time. Current extinction rates are about 100 to 1,000 times higher than the background rate—the normal process of species loss—over the past several million years. And they are accelerating. The chart shows the Living Planet Index, which tracks the abundance of mammals, birds, fish, reptiles, and amphibians. Between 1970 and 2016, the population of species fell globally by 68 percent on average. A recent report by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services showed that 14 of the 18 global ecosystem services assessed were in decline.

Population growth

It took more than 50,000 years for world population to reach 1 billion people. Since 1960, we have added successive billions every one to two decades. The world population was 3 billion in 1960; it reached 6 billion around 2000, and the United Nations projects it will surpass 9 billion by 2037. The population growth rate has been slowing, however, from peak annual rates in excess of 2 percent in the late 1960s, to about 1 percent currently, to half that by 2050.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Aliquam dignissim velit felis, vel mattis justo feugiat vel. Mauris viverra nisi non neque maximus blandit. Etiam efficitur lacus nec arcu iaculis tristique. Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia curae; In convallis rutrum sem ac ultrices. Nam efficitur ac dui in faucibus. Integer dictum diam ut magna dignissim, id elementum ex viverra. Pellentesque non accumsan orci. Aenean posuere quam orci, in mollis eros tincidunt a. Phasellus lobortis sodales vehicula. Praesent sollicitudin purus in metus faucibus, maximus luctus justo vehicula. Maecenas mauris eros, aliquam non dapibus non, euismod eu augue.

Supply and demand

Earlier this year, The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review, commissioned by the UK Treasury, was published. In this study, I sought to show how economics has overlooked Nature. Combining what we know about the biosphere from earth sciences and ecology, the Review sets out a framework for including Nature in our economic thinking and provides a guide for change through three broad, interconnected transitions.

The first is to ensure that our demands on Nature do not exceed its supply. What we demand of Nature (what some term our “ecological footprint”) has for some decades far exceeded Nature’s ability to meet those demands on a sustainable basis, with the result that the biosphere is being degraded at an alarming rate.

This persistent demand overshoot is endangering the prosperity of current and future generations, fueling significant risk for our economies and well-being. Technological innovations—for example, those geared toward sustainable food production—have an important role to play in ensuring that our demands on Nature do not exceed its supply.

But if we are to avoid exceeding the limits of what Nature can provide while meeting the needs of the human population, consumption and production patterns must be fundamentally restructured as well. Policies that change prices and behavioral norms—for example, by aligning environmental objectives along entire supply chains and enforcing standards for reuse, recycling, and sharing—can accelerate efforts to break the links between damaging forms of consumption and production and the natural environment.

Human population growth has significant implications for our demands on Nature, including for future patterns of global consumption. Support for community-based family planning can shift preferences and behavior and accelerate demographic transition, as can improving women’s access to finance, information, and education.

Inclusive wealth

The second transition involves changing our measure of economic success. Reshaping the tools used in economic measurement is a necessary step on that journey. GDP remains a critical measure of economic activity when it comes to short-term macroeconomic analysis. But it is not an appropriate measure of long-term economic performance. This is because it does not tell us how an economy’s assets, particularly its natural assets, are being enhanced or diminished by the decisions we make.

We should instead be using a measure that accounts for the value of all capital stocks—produced capital (roads, buildings, ports, machines), human capital (skills, knowledge), and natural capital. We may call that measure “inclusive wealth.” Comprising all three types of capital, inclusive wealth shows the benefits from investing in natural assets and the trade-offs and interactions between investments in different assets. Only with this more complete picture is it possible to understand whether a country is experiencing economic prosperity. New Zealand’s “wellbeing budget” and the use of “gross ecosystem product” in China are examples explored in the Review of steps being taken to establish that more complete picture.

To illustrate, the export revenues of natural resources (for example, primary products in the tropics) do not reflect the social costs of their removal from the environment; in other words, the trade of these goods does not account for how the extraction process will affect the ecosystem from which they are drawn or the long-term consequences faced by those communities as a result. There is thus a transfer of wealth from countries that export primary products to importing countries. The implication is more than ironic: it is possible that the expansion of international trade has contributed to a massive transfer of wealth from poor countries to rich countries, without its being recorded in official statistics.

Of course, it is not sufficient to account only for natural assets. We need to invest in Nature. That requires a financial system that channels financial investments—public and private—toward economic activities that enhance our stock of natural assets and encourage sustainable consumption and production. Investment can also mean simply waiting; when left alone, Nature grows and regenerates.

Institutional failure

That brings us to the third transition: transforming our institutions to enable change. At the heart of our unsustainable engagement with Nature lies profound institutional failure. Nature’s worth to society—the value of the various goods and services it provides—is not reflected in market prices. The open seas and the atmosphere are open-access resources and have fallen prey to the so-called tragedy of the commons. Such pricing distortions have led us to invest relatively more in other assets, such as produced capital, and underinvest in our natural assets. And since many constituents of Nature are mobile, invisible, or silent, the effects of a number of our actions on ourselves and others—including our descendants—are hard to trace and go unaccounted for, giving rise to widespread externalities.

To exacerbate these distortions, governments almost everywhere pay people more to exploit Nature than to protect it. A conservative estimate of the total global cost of subsidies that damage Nature is about $4 to $6 trillion a year.

A thriving natural environment, underpinned by abundant biodiversity, is our ultimate safety net. Just as diversity within a portfolio of financial assets reduces risk and uncertainty, diversity within a portfolio of natural assets—biodiversity—directly and indirectly increases Nature’s resilience to shocks, reducing risks to the services on which we rely.

Far more global support is needed to raise financial institutions’ understanding and awareness of Nature-related financial risks. Central banks and financial supervisors can do this by assessing the systemic extent of these risks. The IMF, at the center of the global financial safety net, can also play an essential role in both assessing and managing these Nature-related risks in its surveillance and its financial and technical assistance.

The next steps

With heightened awareness of the place of Nature in our lives, a message brought home to us by the pandemic, this year is critical in reimagining our economics and our economic and financial decision-making. World leaders will gather for two conferences—the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (COP15) and the UN Climate Change Conference (COP26)—to discuss the intrinsically linked issues of climate change and biodiversity loss.

The only way to combat this biodiversity crisis is through transformative change, which demands sustained commitment from actors at all levels—from citizens all the way to international financial institutions such as the IMF. The Economics of Biodiversity Review highlights success stories from around the world, demonstrating that the type of change necessary is possible. We must redeploy the ingenuity that allowed humanity’s demands on Nature to grow so large, to bring about the transformation necessary to reimagine our relationship with Nature. We and our descendants deserve nothing less.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.