Mathematician and computer science pioneer Alan Turing will appear on UK currency

One Monday last July, Bank of England Governor Mark Carney strode onto the stage at the Science and Industry Museum in Manchester to reveal the next face of the United Kingdom’s £50 note, one that the bank had earmarked for science.

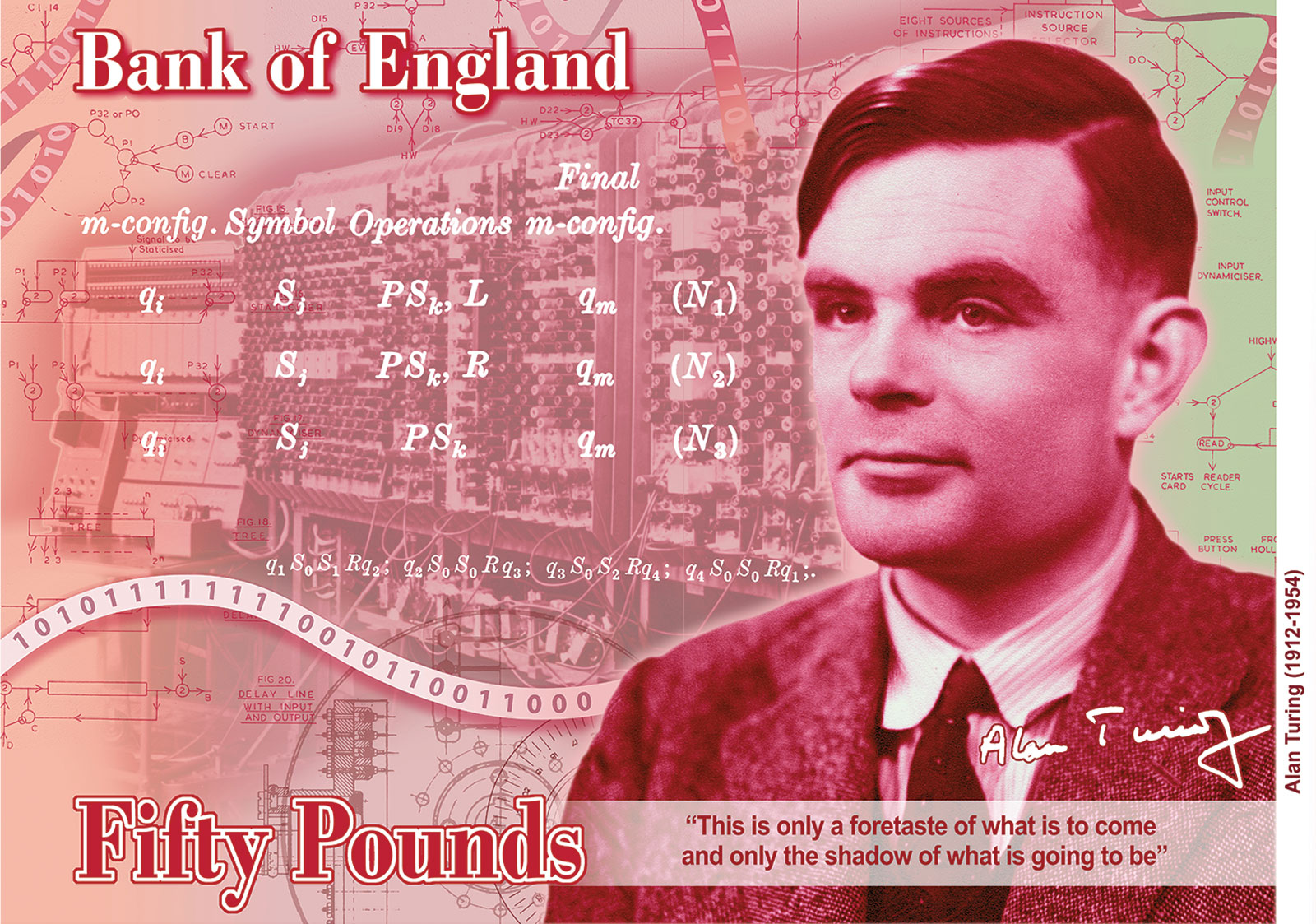

The honor, he announced, would go to Alan Turing (1912–54)—mathematician, World War II code breaker, and father of computer science.

Turing was a visionary as well as a revolutionary, in Carney’s words, and an outstanding mathematician whose work has had a considerable impact on how we live today.

Turing’s seminal 1936 paper “On Computable Numbers” imagined the very concept of modern computing. His code-breaking machine is credited with shortening World War II. And his revolutionary postwar work helped create the world’s first commercial computers and articulated philosophical and logical foundations for artificial intelligence.

He was, Carney said, “a giant on whose shoulders so many now stand.”

Imagining the computer

Celebrated in books and cinema—the 2014 movie The Imitation Game

was based on his biography—Turing is best known by the British public for

his wartime efforts, Sarah John, the Bank of England’s chief cashier, told F&D. With his colleagues at Bletchley Park, the government’s

top-secret codebreaking center, Turing developed the code-breaking Bombe

machine and made other advances in decryption, which, building on work from

Polish mathematicians, led to cracking the German Enigma code. His team’s

work is widely credited with expediting the war’s end, saving millions of

lives.

But it is Turing’s influence as a profound and inventive thinker of the modern digital age that the new £50 is celebrating, according to John.

“If you think about where that idea has taken us between 1936 and today,” said John, referring to Turing’s groundbreaking paper that year, which proposed a computing machine, “and how much computers influence our daily lives—we use them at work, at home, in hospitals, most of us have got a small computer in our pockets that we use on a day-to-day basis—that legacy of starting the computer revolution is really what we’re trying to celebrate on this banknote.”

Turing was selected for the £50 after a months-long “Think Science” campaign by the Bank of England, which elicited nearly a quarter-million nominations from the public, later whittled down by a committee of scientists and central bank officials.

The short list included chemist Rosalind Franklin, instrumental in discovering the structure of DNA; theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking; and Srinivasa Ramanujan, who transformed modern mathematics.

Posthumous apology

Turing also left another legacy. Turing was a gay man during a time when Victorian-era antigay laws were in place. He was arrested and convicted of “gross indecency” for a private relationship and had his government security clearance revoked, effectively putting an end to his career. To avoid prison, he submitted to chemical castration. Turing’s death soon after, at the age of 41, was ruled a suicide.

In 2009 the British government issued a posthumous apology for Turing’s

treatment; he later received a formal royal pardon. And in 2017 legislation

known as the “Alan Turing law” was passed, pardoning those convicted under

the long-

rescinded antigay laws of the time.

Public response to the selection of Turing has been positive, according to John. “Turing’s work has resonated with people in the sense they understand how important computers are to our everyday lives,” John said. But his life story has also resonated and “helped demonstrate that some of the prejudices of the past were really quite unjust and that we’ve come a very long way, but also highlighted how far we still have to go in society,” she added.

A photo of Turing, along with a composite image representing some of his groundbreaking ideas and inventions, will appear on the reverse side of the new £50 notes, scheduled to be issued in late 2021.

Last redesigned in 2011, the £50 bill will be printed on polymer for the first time: it’s much harder to counterfeit and more resilient and has a lower carbon footprint than paper, according to John. (The £5 and £10 notes have already come out on polymer, with the polymer £20 set to be issued in 2020.)

In the United Kingdom as elsewhere, cash use is quickly being supplanted by various forms of digital payments—a fact that Turing himself might appreciate and could potentially have envisioned. (Just 28 percent of UK transactions were in cash in 2018, down from 40 percent in 2016, according to John.) But cash isn’t going anywhere soon, John said. In addition to serving everyday practical purposes for many, physical currency has cultural significance. “People really do care about these banknotes and see them as a symbol of our country.”

Turing will join three other famous British figures on current banknotes: Sir Winston Churchill (on the £5), the novelist Jane Austen (£10), and soon, the artist J. M. W. Turner, who replaces the economist Adam Smith on the £20 note next year.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.