The Case for Universal Social Protection

Everyone faces vulnerabilities during their lifetime

Countries across the world aim to provide social protection for all citizens or residents, generally by a combination of public social insurance and social assistance. Social protection, or social security, includes cash and in-kind benefits provided for children, mothers, and families; support for those sick and without jobs; and pensions for older and disabled persons. These benefit schemes are not only for the poor, as anyone may fall sick, lose a job, or have a child—and everyone inevitably gets old. Governments recognize the existence of universal needs among their citizens—reflecting vulnerabilities that all people are likely to face at least once in their lifetime.

At an international level, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, adopted by world leaders in 2015, commit countries to implementing nationally appropriate social protection systems for all (universal), including floors, for reducing and preventing poverty. This commitment reaffirms the global agreement on the extension of social security achieved by the International Labour Organization’s (ILO’s) 2012 Social Protection Floors Recommendation, which was adopted by workers, employers, and governments from all countries (see box).

Understanding different social protection policies

Universal Social Protection is a policy objective anchored in global commitments such as Article 22 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states that "everyone, as a member of society, has the right to social security," and other international commitments, including International Labour Organization (ILO) standards and Sustainable Development Goal 1.3, part of the United Nations Agenda 2030.

The Global Partnership Universal Social Protection (USP2030) was launched at the United Nations in 2016, led by the World Bank Group and the ILO, showcasing countries that had achieved universal social protection coverage.

A social protection floor is a policy and a standard consisting of a nationally defined set of basic social security guarantees that should ensure, at a minimum, universal access to essential health care and basic income security. It should ensure adequate benefits for children, mothers with newborns, the poor, and the jobless, as well as the sick, disabled, and elderly, through a combination of contributory social insurance and tax-financed social assistance.

Guaranteed minimum income is a means-tested scheme of social assistance generally implemented in countries undergoing austerity or fiscal consolidation. It is not universal but rather targeted to the poor.

Universal basic income is an unconditional cash transfer to all residents in a country (a type of social assistance). Proposals vary considerably in terms of benefit levels, financing mechanisms, and the benefits and services offered; thus some universal basic income proposals have positive social impacts while others result in a net welfare loss. (See "Back to Basics: What Is Universal Basic Income?" in this issue of F&D.)

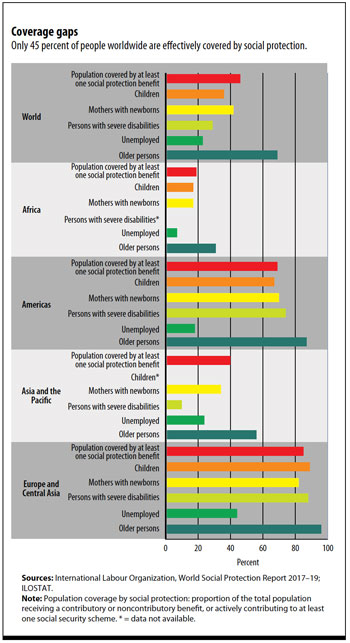

But despite significant progress in the extension of social protection in many parts of the world, only 45 percent of the global population is effectively covered by at least one social protection benefit, while the remaining 55 percent—4 billion people—are left unprotected (see chart).

Coverage gaps are associated with significant underinvestment in social protection, particularly in Africa, Asia, and the Arab states. In many countries benefits are low, keeping people vulnerable. On the positive side, many middle-income countries are advancing fast, and a significant number of countries have achieved universal or near-universal coverage.

Universal social protection is a key element of national strategies to promote human development, political stability, and inclusive growth. Evidence shows that, in addition to reducing poverty and inequality, well-designed social protection systems with adequate benefits

Contribute to inclusive growth: They increase productivity and employability by enhancing human capital, boosting domestic consumption and demand, and facilitating structural transformation of the economy.

Promote human development: Cash transfers facilitate access to nutrition, education, and healthcare; encourage higher school enrollment rates; and bring about a decline in child labor.

Protect people against losses due to shocks, such as economic downturns or natural disasters.

Build political stability and social peace, reducing social tensions and violent conflict.

Beware of short-term reforms

Despite significant progress in the extension of social protection globally, since 2010 a number of countries have undertaken fiscal consolidation or austerity policies. These short-term adjustments to public expenditures, including social protection spending, often undermine long-term development efforts. This is well documented for high-income countries, which have reduced a range of social protection benefits. Together with labor reforms that weakened wages and collective bargaining, these measures have resulted in a declining labor share and contributed to an increase in poverty. Depressed household income levels are leading to lower domestic consumption and lower demand, in turn slowing the economic recovery.

However, fiscal consolidation is also occurring in a majority of developing economies. Many governments are considering cuts or caps to the wage bill and reforming health and social protection systems without sufficient attention to their social impacts—for example, targeting expenditures to the poor instead of expanding social protection coverage to include the middle classes. Reforms driven by a fiscal objective tend to cut social subsidies and expenditures that benefit the majority of the population, replacing them with a safety net for the poorest, thus punishing the middle classes—sometimes dubbed "the missing middle"—in terms of development results. In developing economies, the middle classes have very low incomes and must be supported by development policies, including by adequate social protection.

Recent calls to cut employers’ social insurance contributions, so-called labor taxes, or introduce very low ceilings for insurable earnings could destroy social security systems by constraining their resources and making them unsustainable, thus further increasing poverty and inequality. Social insurance is fundamental to ensure adequate levels of protection and needs to be strengthened.

Relying on individual savings does not deliver meaningful protection for the majority of people. Such proposals ignore the experience of pension privatizations, implemented in about 30 countries, which did not deliver the expected results. Full or partial privatizations underperformed: coverage stagnated, benefits decreased, gender inequalities were compounded, and administration costs proved very high. Systemic risks were transferred to individuals, and fiscal positions worsened significantly given the high transition costs. Many countries that had embarked on pension privatization are now reversing these reforms. Private saving schemes should be a voluntary option for those able to save, but should not replace mandatory public social insurance.

The future of social protection

Universal social protection is at the forefront of the development agenda. Over 100 developing economies are building social protection systems and fast-tracking expansion of benefits to new population groups. Expanding coverage is normally achieved by extending social insurance to the informal sector, supported by social assistance.

Building inclusive social protection systems means making them capable of adapting to demographic changes, the evolving world of work, migration, and fragile contexts. Regarding demographic change, public pension systems are constantly making minor parametric adjustments that, if well designed, should balance equity and financial sustainability, ensuring the primary objective of pension systems, to provide income security for older persons.

Social protection systems are also adapting to new forms of employment. Countries are experimenting with significant innovations that extend social protection coverage to those in the informal economy and facilitating their transition to the formal economy. For example, a number of countries in Latin America have extended coverage to tens of thousands of enterprises and self-employed people by a subsidy combined with a simplified tax and social security contribution mechanism called monotax.

In sum, universal social protection systems, including floors, can powerfully shape countries, enhance human capital and productivity, reduce poverty and inequality, and contribute to inclusive growth and building social peace. Despite some short-term setbacks due to fiscal consolidation and inadequate reforms, countries are advancing fast in the extension of social protection coverage, strengthening public social insurance and social assistance. The ILO and other development partners have important roles in helping countries make this developmental objective a reality for all.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.