Regional Growth Bottoming Out

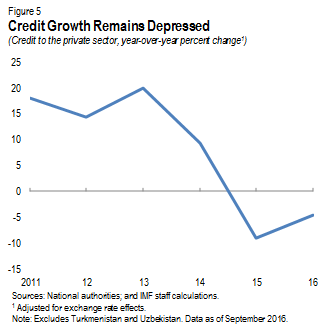

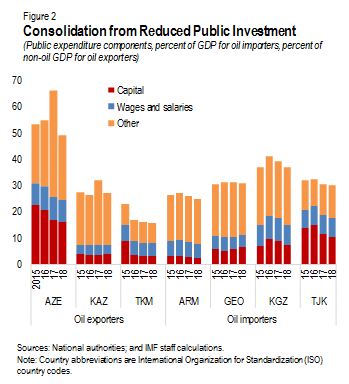

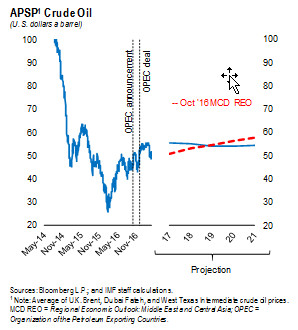

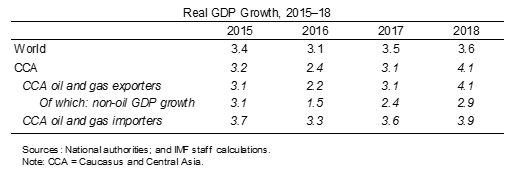

External conditions in 2016 were more favorable than envisioned in the October 2016 Regional Economic Outlook. The prices of oil and other key commodities staged partial recoveries, Russia saw a milder contraction, and growth in China was stronger. In spite of these improvements, the region continued to suffer the lingering effects of earlier external shocks, in particular, the slump in commodity prices since mid-2014, and weak economic activity in key trading partners. Growth in the CCA was 2.4 percent in 2016, 1 percentage point higher than projected last October, yet 0.8 percentage point lower than in 2015 (Figure 1).  The improvement relative to October also reflected significant revisions to economic activity in Kazakhstan due to the impact of currency adjustment, lagged effects of earlier fiscal stimulus, and oil production from the new Kashagan field.

The improvement relative to October also reflected significant revisions to economic activity in Kazakhstan due to the impact of currency adjustment, lagged effects of earlier fiscal stimulus, and oil production from the new Kashagan field.

With the slightly more benign external conditions anticipated to continue, growth in the CCA is projected to pick up to 3.1 percent in 2017 and further accelerate to 4.1 percent in 2018.

However, despite recent improvements, external conditions are expected to remain relatively subdued over the medium term. At the same time, the legacy of earlier external shocks has left the CCA more vulnerable, with higher public debt and weak financial sectors. In that context, CCA growth is projected to average 4.3 percent in 2018–22, well below the 8.1 percent the region experienced in 2000–14.

In oil exporters, growth slowed to 2.2 percent in 2016, 0.9 percentage point lower than in 2015 and the lowest since 1998. In Azerbaijan, growth fell due to the impact of lower oil production in the context of lower oil prices, a sharp weakening of construction activities, and the drag from financial sector vulnerabilities. In Kazakhstan, growth slowed, despite relatively strong activity in agriculture, construction, and transportation.

Growth for CCA oil exporters is projected to rebound to 3.1 percent this year and further accelerate to 4.1 percent in 2018, though with some differences across countries. In Kazakhstan, growth is projected to pick up this year and next, supported by higher oil production from the Kashagan field, the continued impact of earlier targeted fiscal stimulus initiatives, and the assumption that financial sector issues will be tackled and, consequently, that bank credit will resume. Economic activity in Azerbaijan is projected to improve only gradually, curtailed by lower oil production this year, in line with the recent OPEC+ agreement, the impact of ongoing financial vulnerabilities, and the foreseen impact of fiscal consolidation. Both Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan are expected to experience relatively steady growth over the next few years, although a large external deficit will be an impediment to economic activity in Turkmenistan. Over the medium term, growth in oil exporters is projected to continue to pick up, in part reflecting more favorable economic conditions in China and Russia.

For oil importers, owing to the lingering impact of lower commodity prices and reduced remittance flows, growth in 2016 amounted to 3.3 percent, the lowest since the global financial crisis. This reflects weaker-than-anticipated domestic demand in Armenia, exacerbated by a poor agricultural harvest, and in Georgia. In contrast, stronger trade, construction, and agricultural activities supported growth in the Kyrgyz Republic, while Tajikistan’s pickup in economic activity came from stronger investment.

As remittance flows and external demand recover—supported by higher prices of key commodities, including copper, aluminum, cotton, and gold—growth in CCA oil importers is projected to accelerate to 3.6 percent in 2017 and 3.9 percent in 2018 and continue to improve over the medium term.

Fiscal Consolidation Needed

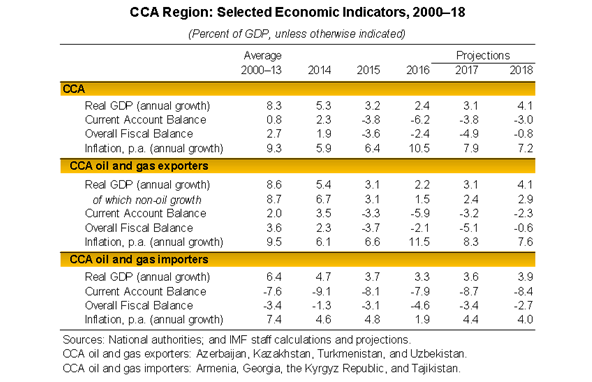

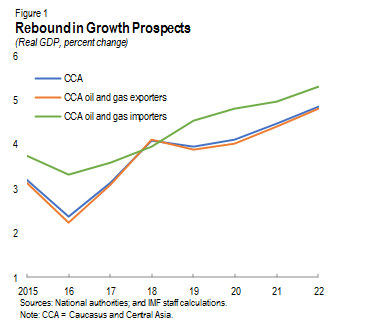

With few exceptions, overall fiscal balances deteriorated in 2016, especially among oil importers. Policymakers continued to use fiscal policy to offset the impact of earlier external shocks, with public expenditure increasing in most countries (Figure 2). While this provided much needed support to economic activity, fiscal space has declined and public debt is higher (see below).  Most countries are therefore in a more vulnerable position, and are expected to reduce spending this year and next. This consolidation is anticipated to materialize mostly through reduced public investment, which, in some instances, will reflect the appropriate reversal of past investment booms that have generated little improvement in productivity or growth. In that context, countries need to focus on strengthening the efficiency of public spending, and ensuring the preservation of critical social expenditure that protects the poor and vulnerable. Countries need to develop strong frameworks to identify and monitor growth-enhancing public investment projects.

Most countries are therefore in a more vulnerable position, and are expected to reduce spending this year and next. This consolidation is anticipated to materialize mostly through reduced public investment, which, in some instances, will reflect the appropriate reversal of past investment booms that have generated little improvement in productivity or growth. In that context, countries need to focus on strengthening the efficiency of public spending, and ensuring the preservation of critical social expenditure that protects the poor and vulnerable. Countries need to develop strong frameworks to identify and monitor growth-enhancing public investment projects.

- For oil exporters, the non-oil fiscal deficit amounted to 14.9 percent of non-oil GDP in 2016, an improvement of 3.6 percentage points relative to the previous year. This reflects mainly reduced capital expenditure, and a pickup in non-oil revenues in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan, largely as a result of currency adjustment. The non-oil fiscal deficit for oil exporters is projected to increase to 20.6 percent (of non-oil GDP) in 2017. This is explained primarily by a one-time support package to the banking system in Kazakhstan, and an extraordinary transfer from the Oil Fund to the Central Bank of Azerbaijan for the repayment of debt obligations. In 2018, the deficit is projected to decline to 13.5 percent as Azerbaijan continues to reduce nonproductive public investment, and Kazakhstan’s fiscal stimulus expires.

- For oil importers, the overall fiscal deficit rose to 4.6 percent of GDP in 2016, 1.5 percentage points larger than in 2015. This reflects increased spending in all countries, especially the Kyrgyz Republic, where fiscal accommodation continued amid a shortfall in tax revenues. Overall deficits for this group are projected to decline to 3.4 percent in 2017 and 2.7 percent in 2018. With revenues anticipated to remain broadly unchanged, these reductions rely on the implementation of consolidation plans that include, for example, lower public investment in Armenia and lower current expenditures in Georgia.

With subdued growth prospects, the pace of fiscal consolidation must be well calibrated. Too much fiscal restraint could negatively affect growth and impede economic diversification efforts; too little could compromise medium-term fiscal sustainability. This is especially true given that public debt, while still low relative to international standards, has increased rapidly in many CCA countries, and further increases are anticipated over the next few years (Figure 3).

Of particular concern is the share of public debt denominated in foreign currency. On average, almost half of the increase in public debt reflects valuation changes from local currency depreciations since 2014. To reduce reliance on external financing, and as part of a broader effort to reduce dollarization and develop domestic financial markets, some countries, such as Kazakhstan, are planning to introduce a broader range of debt instruments denominated in local currency. A second concern arises from the fact that, in some countries, borrowing by state-owned enterprises is not recognized as a contingent liability, which implies that consolidated government obligations might be underestimated. To secure fiscal sustainability, countries should continue to focus on developing credible multiyear fiscal frameworks that guide the pace of adjustment and are reinforced by well-designed policies that aim to identify new sources of income and reduce their dependence on commodity-related revenue. With increased exchange rate flexibility in the region, asset-liability management frameworks—covering sovereign wealth funds and foreign exchange reserves—should be reviewed to ensure they adequately capture the full extent of balance sheet risk exposures.

A More Favorable External Environment

Current account deficits widened in most CCA countries in 2016, largely reflecting the effects of the various external shocks that have hit the region since 2014. Better prospects for growth in key trading partners, especially China and Russia, combined with the firming of commodity prices, are anticipated to contribute to a reduction in the current account deficits of oil exporters over the next few years. However, little improvement is anticipated in the current account deficits of oil importers.

Among oil exporters, the projected current account deficit of 3.2 percent of GDP in 2017 implies an improvement of 2.7 percentage points relative to the previous year, effectively reverting to 2015 levels. The current account deficit for the group is anticipated to improve further to 2.3 percent of GDP in 2018, due to a sharp acceleration in exports, partly associated with higher oil prices and improved external demand.

Oil importers’ current account deficit is set to widen to 8.7 percent of GDP in 2017, from 7.9 last year, but marginally improve to 8.4 percent in 2018. Higher prices of imports, driven by higher oil prices and currency depreciation, are expected to be only partially offset by a pickup in remittances and an increase in the value of commodity exports.

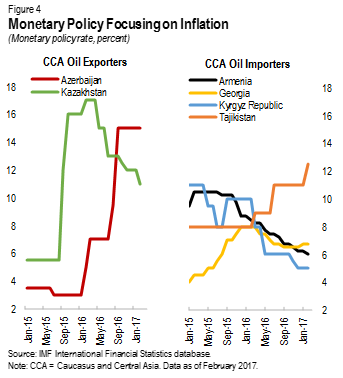

Monetary Policy to Be Focused on Inflation

At 11.5 percent last year, inflation among oil exporters reached double digits for the first time in eight years. This reflects the effects of past depreciations in Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan due to the large negative terms-of-trade shock. In Azerbaijan, inflation was also affected by increases in the administrated prices for gas and electricity and the introduction of import duties on agricultural products. Inflation in oil exporters is expected to decline to 8.3 percent in 2017 and 7.6 percent in 2018. These projections reflect easing inflation pressure in Kazakhstan associated with the recent appreciation of the tengeand lower government spending. Moderating inflation prospects in Azerbaijan due to the projected fiscal consolidation are also a factor, as well as tighter monetary policy as the country moves toward a fully flexible exchange rate regime—the Central Bank of Azerbaijan announced a move to a free- floating exchange rate regime in early January 2017.

With the exception of Tajikistan, inflation among oil importers in 2016 was lower than in the previous year, with average inflation for this group declining to 1.9 percent, some 3 percentage points lower than in 2015. Deflation continued in Armenia from weak domestic demand and lower import prices. The Kyrgyz Republic saw near zero inflation amid subdued growth, currency appreciation, and declining food prices. Inflation in Georgia declined as a result of weak demand and low global oil and food prices. However, as economic activity continues to recover, inflation in oil importers is projected to accelerate to 4.4 percent in 2017 and remain around 4 percent in 2018.

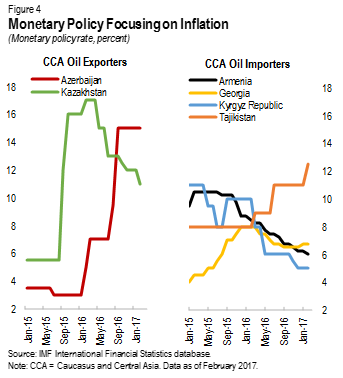

As countries continue to move toward increased exchange rate flexibility, monetary policy will need to continue to focus on inflation developments. Currency stabilization and easing inflation pressure have allowed some central banks to reduce policy rates on various occasions since early 2016. This has been the case in Kazakhstan, among oil exporters, as well as in Armenia, Georgia, and the Kyrgyz Republic, among oil importers (Figure 4). Conversely, monetary policy tightened significantly in Azerbaijan to support the exchange rate and to address inflation pressure and, to a lesser extent, in Tajikistan, also to stem inflation pressure from currency depreciation and excess liquidity.

Further improvements to monetary policy frameworks are needed to support exchange rate flexibility and inflation targeting. This requires a  sustained effort to develop appropriate policy instruments and strengthen central bank independence, analytics, and communications to establish the credibility critical for the success of these frameworks.

sustained effort to develop appropriate policy instruments and strengthen central bank independence, analytics, and communications to establish the credibility critical for the success of these frameworks.

Financial Sector Weaknesses

Need to Be Resolved

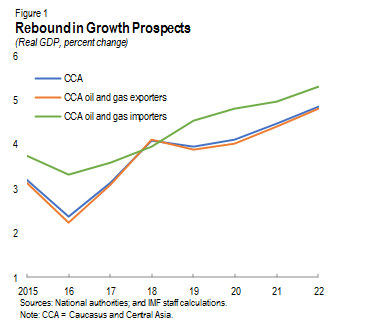

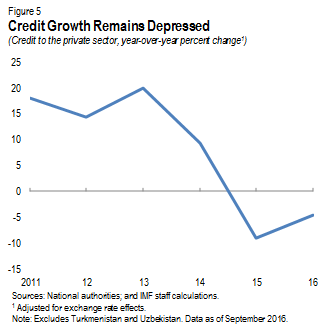

Financial sector vulnerabilities continue to increase, and repair is urgently needed. With few exceptions, restructured and overdue loans have increased further as dollarization remains high and banks remain undercapitalized. These weaknesses represent a drag on future economic activity with credit growth continuing to decline in a number of countries (Figure 5). At the same time, lack of transparency and ownership issues continue to inhibit operations and reduce confidence in the banking sectors of several countries. In some cases, governance issues and limited supervisory independence impede the resolution of deep-rooted problems.

Against this backdrop, authorities have taken some steps to address these vulnerabilities. In Armenia, for example, all banks have complied with the recent central bank-mandated increase in minimum capital, which has also led to some mergers and a consolidation of the banking system. In Georgia, efforts to strengthen the regulatory framework and reduce dollarization are underway. In Azerbaijan, capital injections and government purchases of bad loans continue, but additional bank closures might be necessary as new capitalization plans are developed. In Kazakhstan, the authorities are engaged in the merger between the two largest banks, which will require significant public financial support.In Tajikistan, a recapitalization plan for two major banks and the liquidation of two smaller banks have been announced. However, financial sector weaknesses continue in that country, with regulatory forbearance and resolution of nonperforming loans remaining a challenge.

For the CCA more broadly, much remains to be done to contain risks and enhance financial intermediation. And this will be challenging in this difficult context of legacy and governance issues, coupled with regulatory forbearance and subdued economic growth. First, any weaknesses with bank balance sheets must be properly diagnosed and effectively remedied. Second, timely intervention of weak banks is crucial to avoid systemic risks. Support for bank resolution needs to be provided under strict conditions. For example, public funds should support only viable systemic institutions, with well-defined and fully collateralized guarantees, and shareholders must not retain any claims on assets when support is provided. Liquidation of bad assets—and allowing new investors to purchase these assets—should follow a transparent and market-oriented approach that promotes competition in the banking system. Forbearance must be avoided and corporate governance of state-owned enterprises, major debtors in many jurisdictions, should be improved. In parallel, regulators should continue to strengthen lending practices and crisis management frameworks while enforcing prudential regulations. Addressing financial sector issues promptly could have positive implications for growth, not only as financial intermediation accelerates but also as potential pressures on public finances diminish.

With Risks Tilted to the Downside, the Need for Structural Reform Is Even More Urgent

While baseline assumptions point to a pickup in growth, risks to the outlook for the CCA region remain to the downside, including, for some countries, due to regional geopolitical tensions. A weaker-than-expected recovery could undermine prospects for credible fiscal consolidation plans. At the same time, failing to quickly address financial sector weaknesses could not only reduce growth prospects further, but would also increase systemic risk, adding to fiscal pressures in a number of CCA countries.

In this context, the external shocks that have hit the region since 2014 have increased the urgency of diversifying away from oil and other commodities and reducing reliance on remittances. This is ever more important considering the large uncertainty surrounding the policy positions in the United States and other advanced economies, which could have significant global ramifications (see Global Developments section). Although trade and financial linkages with advanced economies are relatively limited for CCA countries, the effects on key trading partners that could arise from an inward shift in policies, including toward protectionism, and a subsequent disruption of trade and capital flows, could be significant. The impact of lower global growth on key commodity prices would also dampen the regional outlook.

In contrast, firming prices of oil and other commodities, together with a somewhat more favorable outlook in key trading partners, risk leading to complacency, which in turn could delay the implementation of the structural reforms needed to unleash the region’s growth potential. While some initiatives have been launched—such as the 100 Concrete Steps in Kazakhstan and the Four Point Reform Plan in Georgia, which cover administrative reforms, improvements in the business environment, and the strengthening of the legal framework—their implementation will require a reduction in the role of the state, which may prove challenging. Any delays to the reform process in the CCA could further stall gains in living standards in these countries.

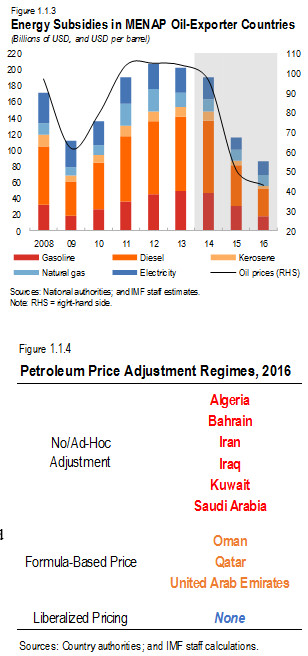

Across MENAP oil exporters, the sharp fall in oil prices between late 2014 and the second quarter of 2016 was reflected in a surge in fiscal deficits (blue bars in Figure 1.2). The average fiscal deficit reached about 10 percent of GDP in both 2015 and 2016. However, the underlying fiscal stance, which is measured by the non-oil primary balance and excludes the effect of oil price movements, improved substantially in 2016, with non-oil primary deficits reduced by 5¼ percentage points of non-oil GDP in the GCC (driven by Oman and Qatar) and 11 percentage points in Algeria (diamonds in Figure 1.2). This improvement resulted from energy price reforms and spending cuts (Algeria, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia), as well as increases in non-oil revenue in some countries (Algeria, Oman, Saudi Arabia). In Iran, the fiscal stance was loosened slightly to support non-oil growth, while in countries in conflict as a whole it tightened.

Across MENAP oil exporters, the sharp fall in oil prices between late 2014 and the second quarter of 2016 was reflected in a surge in fiscal deficits (blue bars in Figure 1.2). The average fiscal deficit reached about 10 percent of GDP in both 2015 and 2016. However, the underlying fiscal stance, which is measured by the non-oil primary balance and excludes the effect of oil price movements, improved substantially in 2016, with non-oil primary deficits reduced by 5¼ percentage points of non-oil GDP in the GCC (driven by Oman and Qatar) and 11 percentage points in Algeria (diamonds in Figure 1.2). This improvement resulted from energy price reforms and spending cuts (Algeria, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia), as well as increases in non-oil revenue in some countries (Algeria, Oman, Saudi Arabia). In Iran, the fiscal stance was loosened slightly to support non-oil growth, while in countries in conflict as a whole it tightened.

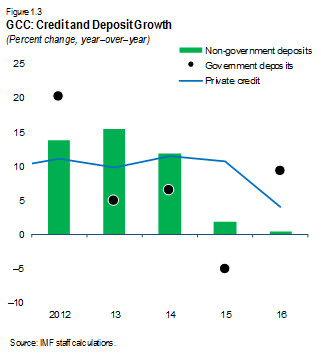

To support credit, banks increased foreign wholesale funding (Bahrain, Qatar) and substituted from foreign assets (Oman, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates). However, credit growth slowed significantly in 2016. Beyond 2016, credit demand could decelerate further as higher U.S. interest rates are reflected in lending rates, although idiosyncratic factors—the 2022 FIFA World Cup (Qatar) and Expo 2020 (Dubai)—will support credit demand in Qatar and the United Arab Emirates.

To support credit, banks increased foreign wholesale funding (Bahrain, Qatar) and substituted from foreign assets (Oman, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates). However, credit growth slowed significantly in 2016. Beyond 2016, credit demand could decelerate further as higher U.S. interest rates are reflected in lending rates, although idiosyncratic factors—the 2022 FIFA World Cup (Qatar) and Expo 2020 (Dubai)—will support credit demand in Qatar and the United Arab Emirates.

The improvement relative to October also reflected significant revisions to economic activity in Kazakhstan due to the impact of currency adjustment, lagged effects of earlier fiscal stimulus, and oil production from the new Kashagan field.

The improvement relative to October also reflected significant revisions to economic activity in Kazakhstan due to the impact of currency adjustment, lagged effects of earlier fiscal stimulus, and oil production from the new Kashagan field.  Most countries are therefore in a more vulnerable position, and are expected to reduce spending this year and next. This consolidation is anticipated to materialize mostly through reduced public investment, which, in some instances, will reflect the appropriate reversal of past investment booms that have generated little improvement in productivity or growth. In that context, countries need to focus on strengthening the efficiency of public spending, and ensuring the preservation of critical social expenditure that protects the poor and vulnerable. Countries need to develop strong frameworks to identify and monitor growth-enhancing public investment projects.

Most countries are therefore in a more vulnerable position, and are expected to reduce spending this year and next. This consolidation is anticipated to materialize mostly through reduced public investment, which, in some instances, will reflect the appropriate reversal of past investment booms that have generated little improvement in productivity or growth. In that context, countries need to focus on strengthening the efficiency of public spending, and ensuring the preservation of critical social expenditure that protects the poor and vulnerable. Countries need to develop strong frameworks to identify and monitor growth-enhancing public investment projects.

sustained effort to develop appropriate policy instruments and strengthen central bank independence, analytics, and communications to establish the credibility critical for the success of these frameworks.

sustained effort to develop appropriate policy instruments and strengthen central bank independence, analytics, and communications to establish the credibility critical for the success of these frameworks.