Europe: Turning the Recovery into Enduring Growth

May 14, 2024

As prepared for delivery.

Good afternoon.

Thank you, Mr. Kisselevsky, for the kind welcome and the ECB for hosting us today.

Today's seminar takes place two years after Russia's invasion of Ukraine, a large energy shock, and the emergence of a more divided global economy.

Europe has successfully navigated through this tumultuous period, and a soft landing has now come within reach.

But this also puts the spotlight on what may be Europe’s more fundamental problem: to sustain the recovery and lift its still miserable-looking medium-term growth outlook.

Here an important new debate has begun about the blueprint for Europe’s future growth model. Just two weeks ago, two important reports were released. Enrico Letta's “Much more than a market”[1] and Christian Noyer's “Developing European capital markets to finance the future.”[2] They outline in convincing fashion the case for a more integrated, green, and inclusive Europe.

In today’s speech, I will outline what we see as Europe’s main growth challenge; provide you with estimates of what reforms can potentially achieve; and outline what Europe needs to do to reap these potential gains.

Europe’s Recovery is on Track

Let me start with some good news.

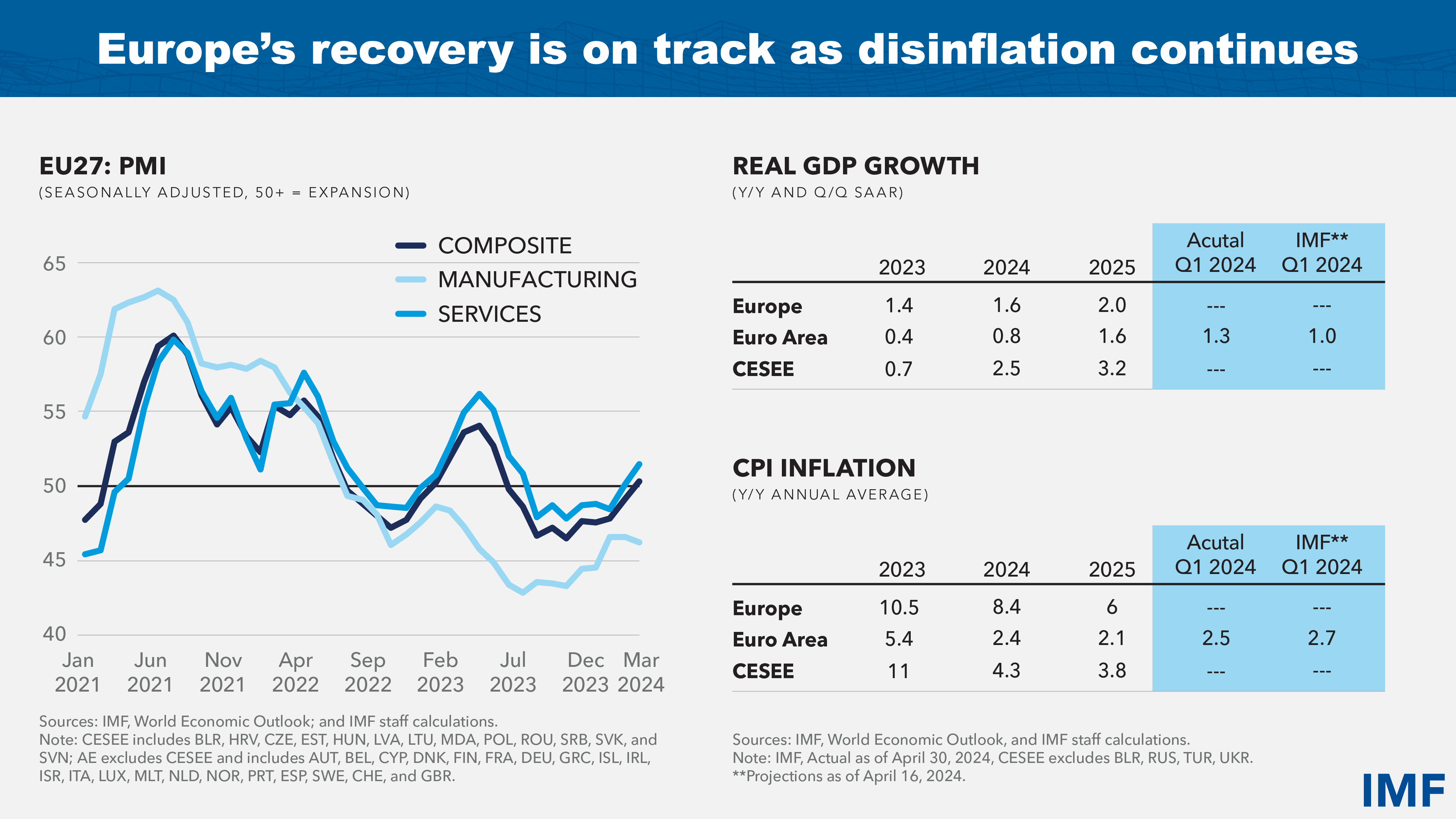

Europe's recovery, fueled by domestic demand, is firmly on track. The latest GDP data for the euro area show growth slightly above expectations, with all major economies performing slightly better than anticipated in our April 2024 Regional Economic Outlook.

The recovery is driven by improving consumer and business sentiment. Household incomes are supported by resilient labor markets which have aided a recovery in incomes.

In many countries disinflation has continued and is paving the way for interest rate reductions. As of April 2024, headline inflation in the euro area has remained stable at 2.4 percent. Core inflation has also decelerated.

Despite this positive news, inflation rates remain elevated in several European countries, this necessitates a careful and measured approach to monetary policy easing.

We project that the ECB will reduce its policy rate starting in June with cuts of 25 basis points each quarter until it reaches a neutral stance at 2.5 percent in September 2025. This seems appropriate under our baseline scenario.

In Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe countries, we also see rate cuts ahead. But disinflation has further to go. For that reason, monetary policy will need to remain tight for an extended period.

Finally, a brief word about fiscal policy. The current recovery also provides the opportunity for more ambitious fiscal consolidation. Labor markets are tight, public debt ratios have risen, and output gaps are near zero in many countries. For these reasons we recommend a less-backloaded deficit reduction than currently envisaged for 2024-25.

While Europe is doing better now, deep structural challenges—aging, climate change, and global fragmentation— await. Unfortunately, Europe does not enter this period from a position of economic strength.

Europe's Critical Weakness: Low Productivity

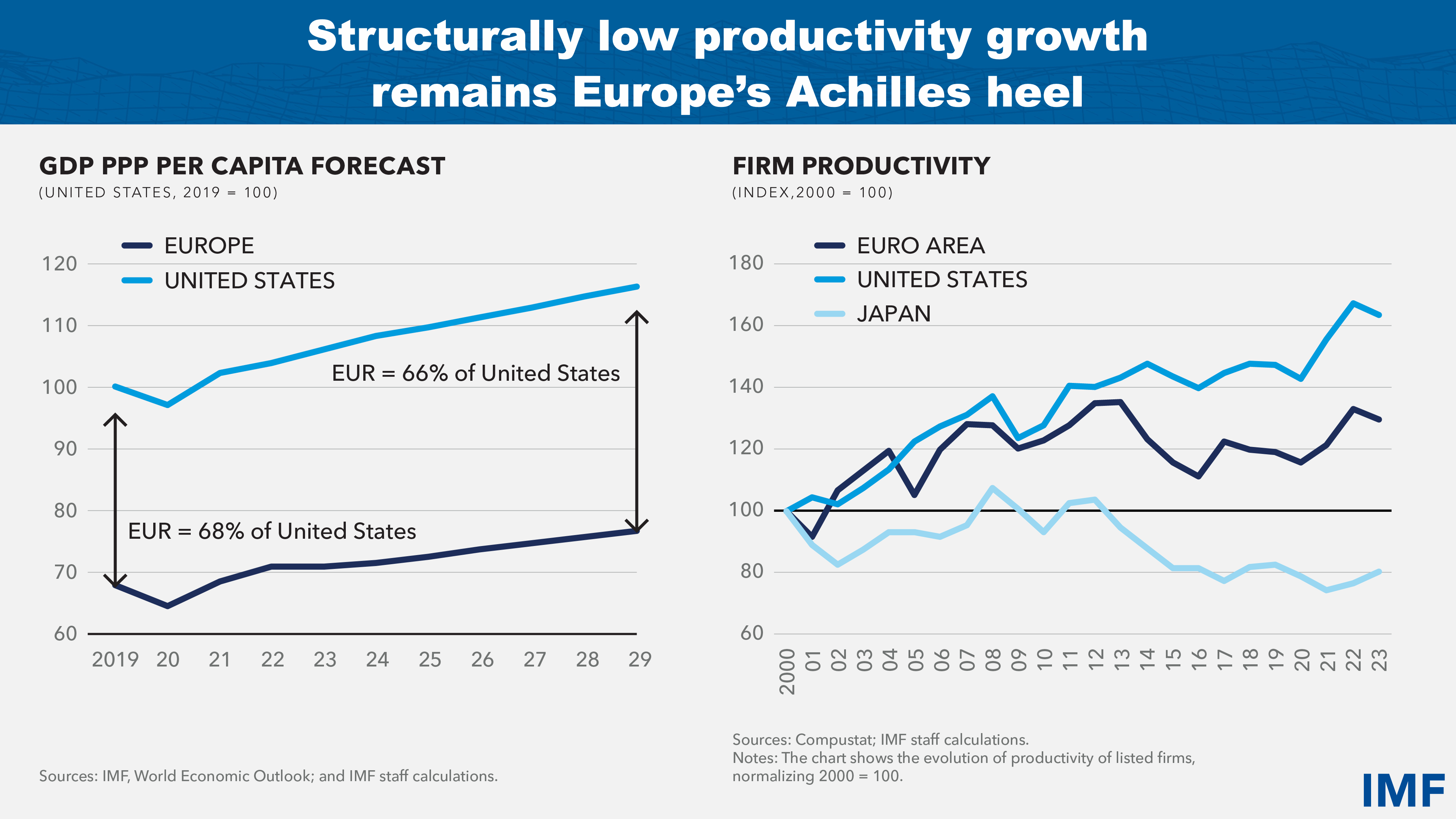

Europe’s income levels are below the global frontier. Compared to the United States, the average EU per capita income is around one-third lower than in the United States. This gap is large and has widened over the last two decades even for many of the wealthier economies.

Under current policies, this gap is unlikely to narrow for decades to come.

The primary factor behind the income disparity with the United States is Europe's lower productivity. A smaller EU capital stock and labor input explain about one third of the difference. However, the bulk of the gap—nearly 70 percent—can be attributed to lower productivity. The comparison holds true if more granular data, such as aggregate hours worked are being used.

This pattern is also reflected in data at the firm level. Since 2005, US businesses have consistently outperformed European firms, with the productivity gap widening even further after 2014.

Economic Integration Lifts Incomes…

What can Europe do? The way to higher growth may lead through the Single Market.

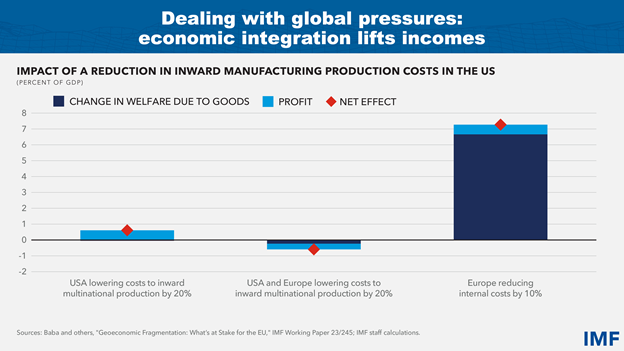

A recent IMF study [3] finds that reducing remaining barriers to the Single Market for goods and services by 10 percent could raise European output by as much as 7 percentage points over the long term.

Trade integration in the EU is still only a fraction of the level observed among US states. Services trade, in particular in transportation, distribution, and logistics, remains constrained.

These markets need to be opened up to raise incentives for productivity improvements.

Where they are open, harmonized regulations, lower administrative and legal barriers, and streamlined trade procedures would also lower business costs. Better border infrastructure, such as transportation, ICT, energy, and financial payments within Europe alone could lift Europe’s trade and incomes by about 1.6 percent over the long-term.[4]

…and Helps Counter Global Fragmentation Risks

Strengthening the Single Market along these dimensions will not only help growth—it is also the right answer to geoeconomic fragmentation as it strengthens resilience. When Europe’s trading partners increasingly use inward-looking and protectionist policies, the best response for Europe is to lower its internal barriers and realize the potential of its large market.

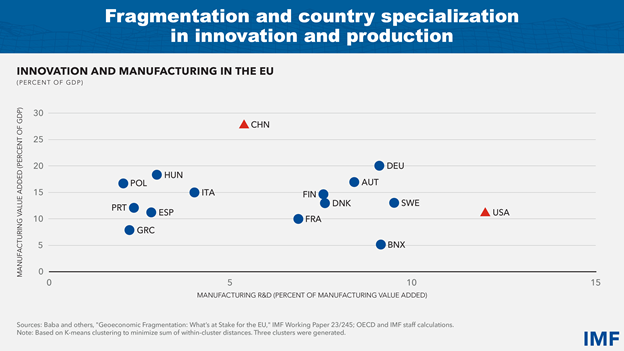

Indeed, Europe is in a unique position among the main global blocs. While the US is specialized in innovation and China in manufacturing, Europe has capabilities in both areas: it innovates and has affordable manufacturing locations. This middle place offers Europe an advantage that allows it to grow in the face of rising fragmentation pressures.

Market Integration also Aids Energy Security

Another benefit of a more deeply integrated Single Market is energy security. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, European energy security needs have risen. In a forthcoming study we find that integration would improve energy security along two dimensions: security of supply and economic resilience.[5]

The example of the electricity markets is instructive. Deeper integration would increase electricity trade between European countries. Even though more electricity trade would increase import dependence, it would reduce the geographic concentration of energy imports among non-European suppliers. Countries also become less sensitive to energy supply disruptions because energy prices and hence energy expenditures fall.

A Blind Subsidy War Would Reduce Incomes…

In addition to free trade, the Single Market has two other key dimensions—capital and labor—that are also critical for Europe’s growth and its resiliency. But before I turn there, let me briefly discuss how not to address fragmentation when it comes to subsidies.

Engaging in a subsidy race in response to the global surge of industrial policies does more harm than good.[6] Implementing policies that are not coordinated across the European Union could severely disrupt the integrity of the single market. It could adversely affect member states, and ultimately slow productivity growth.

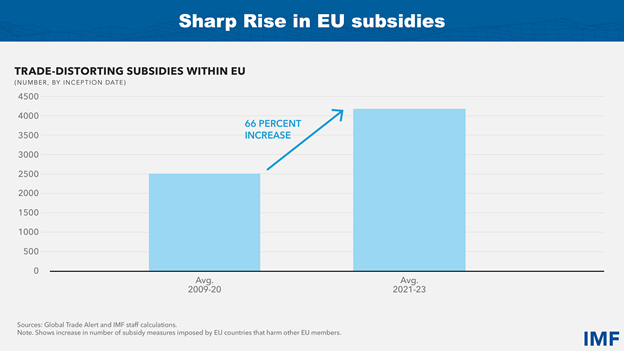

There is, however, a concerning trend. Since the start of COVID, the number of subsidy measures imposed by EU countries that detrimentally affect other members, has surged by more than 50 percent. In forthcoming work, we find that national state aid creates larger employment and revenue losses for competitors than the gains generated for the recipients.[7] The effects can be even more pernicious if the measures induce tit-for-tat policies between governments.[8]

…Suggesting Careful Use of State Aid, Preferably Together

This is not to say that there is no room for subsidies.

In cases of well-identified externalities, subsidies can improve welfare. Europe already has the tools to address externalities while preserving the level playing field of the Single Market. Examples include carbon taxes or infrastructure user fee schemes for roads and network services. But countries should not go it alone. They should deploy them at the EU level to maximize gains.

Finally, in situations where strategic considerations come into play, such as those related to economic or national security, subsidies need to be applied with precision. They should be narrowly targeted. This ensures they do not become too costly and do not compromise the competitive landscape.

Enhancing Productivity and Competitiveness also Requires Better Integrated Capital and Labor Markets

What else can Europe do to achieve faster productivity growth?

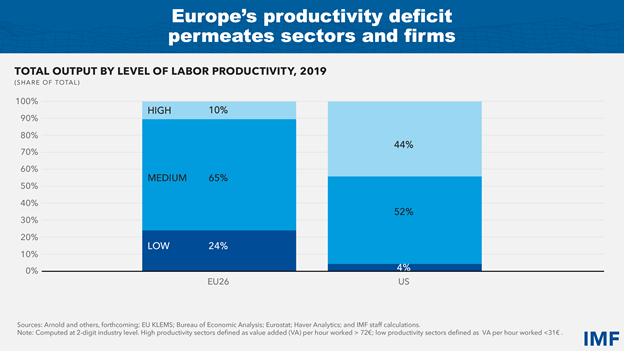

Let me step back and first recognize that Europe’s productivity deficit extends across sectors and firms. The following chart is illustrative.

The share of Europe’s high-productivity sectors in total output (10 percent) is about one-fourth of the share in the United States (44 percent), while the share of low-productivity activities in Europe is much larger than in the United States.

To enhance productivity, Europe requires either more or larger firms at the productivity frontier. It must also elevate medium-productivity firms to high performers and enable low-productivity businesses to either catch up or make room for high-labor productivity firms offering better-paying jobs.

Advancing the Capital Market Union

The Capital Market Union is critical to catalyze productivity growth across the entire spectrum of firms.

Indeed, for Europe, creating a true capital market union is not about mobilizing more savings. With unrestricted access to global and European savings, the challenge is not a lack of funds but of removing barriers that prevent capital from flowing to where it can be most productive.

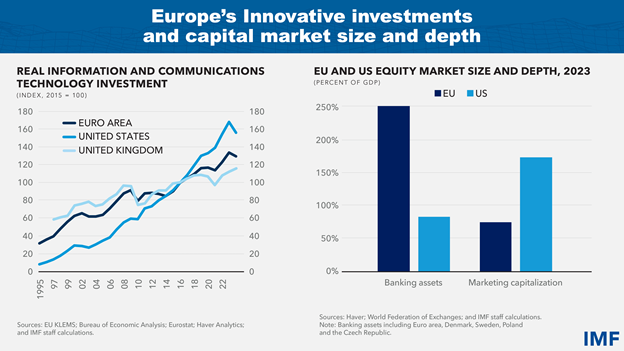

Currently, there are still large gaps between the United States and Europe in research and development expenditures in crucial technologies. In areas such as software and electronics use Europe has fallen behind. Similarly, the adoption of new technologies in the areas of robotics, big data, artificial intelligence, and mobile networks is not as advanced.

Progress in these strategic areas requires higher private investment and public spending. But the number of markets firms participate in is limited because it is often too costly for them to operate in different jurisdictions. This in turn stymies investment in productivity improving technologies, What Europe needs are simpler regulations and tax procedures for investment income, harmonized accounting and bankruptcy frameworks, and integrated capital market supervision.

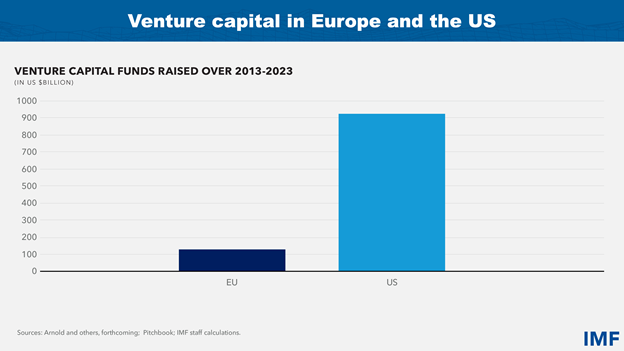

A second area where a complete capital market union can make a difference is venture capital. Compared to the US, EU countries have 10-fold less funds over the less decade for startups or ventures who strive to become established enterprises.[9]

EU capital markets have remained segmented across national borders, with institutional investors displaying significant home bias. As a result, EU equity markets are smaller and less liquid than in the US, resulting in lower valuations for listed firms.

To grow a thriving venture capital ecosystem, a larger pool of risk capital is needed. Policies can help to some extent. For instance, expanding funding from long-term investors, such as pension funds and insurance companies, could lead to a significant increase in available venture capital. This would make it easier for innovative entrepreneurs and small firms to scale up, while staying in Europe. Capital market development would also facilitate a successful “exit” for early stage investors, raising incentives to further investment in dynamic firms.

Finally, developing EU-wide financial products tailored to households could be considered. For instance, private pension products with uniform tax treatment across EU countries could broaden the base of capital investors and contribute to this endeavor.

Stronger and Better Integrated Labor Markets

The final ingredient for a more productive Europe is a larger pool of qualified workers. This needs to be pursued in three ways: by making labor mobility more attractive, by activating underutilized workers, and by strengthening skills of workers.

Let me start with the labor mobility: the cost of relocating between EU member states is about eight times higher than for relocation between US states.[10] Measures to reduce these costs include recognition of academic and professional qualifications, better portability of pensions (part of the CMU agenda), and easier access to language training. Such initiatives can enhance cross-border mobility and facilitate talent movement from low-productivity to high-productivity firms, which are often concentrated geographically.

What about expanding the labor force? European workers have shorter work weeks and retire earlier than in other regions. Enhancing incentives for prolonged work lives and addressing remaining obstacles to female labor force participation, particularly in child and elderly care, at the national level, can alleviate labor shortages. Furthermore, integrating cross-border workers effectively and enhancing public services in regions experiencing population growth are crucial. Simultaneously, reducing barriers to recruiting skilled workers from outside the EU can address skills gaps and enhance productivity.

Moreover, Europe needs well-designed education policies that mitigate skill mismatches while jobs are being destroyed and created. Reskilling and upskilling should focus on enhancing digital skills, addressing knowledge deficits, and fostering preemptive acquisition of new skill through lifelong learning. Future workers will need to adapt well to a rapidly changing economic and technological environment in the age of artificial intelligence.

It is Time For Europe to Re-Accelerate Integration

Europe has made immense progress in integration, economically and politically, yielding substantial benefits.

The journey needs to continue without any further delay. A fully integrated Single Market would greatly enhance productivity and, as a result, the EU’s competitiveness. Undertaking the reforms to achieve a true Single Market would show once again how Europe can overcome even the most severe obstacles when acting decisively and together.

Thank you.

[1] Letta, Enrico, 2024. “Much More than a Market.”

[2] Noyer, Christian. 2024. “Developing european capital markets to finance the future”.

[3] Baba, Chikako, Ting Lan, Aiko Mineshima, Florian Misch, Magali Pinat, Asghar Shahmoradi, Jiaxiong Yao, and others. 2023. “Geoeconomic Fragmentation: What’s at Stake for the EU.” IMF Working Paper 2023/245, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

[4] Felbermayr, Gabriel J., and Alexander Tarasov. 2022. “Trade and the Spatial Distribution of Transport Infrastructure.” Journal of Urban Economics 130: 103473.

[5] Dolphin, Geoffroy, Romain Duval, Hugo Rojas-Romagosa, and Galen Sher. Forthcoming. Forthcoming. “Secure Energy in Europe’s Green Transition.” IMF Departmental Paper, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

[6] Felbermayr, Gabriel J., and Alexander Tarasov. 2022. “Trade and the Spatial Distribution of Transport Infrastructure.” Journal of Urban Economics 130: 103473.

[7] Brandao-Marques, Luis and Hasan Halit Toprak. Forthcoming. “Impact of State Aid on Firm Performance and the Single Market in the European Union.” IMF Working Paper, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

[8] Rotunno, Lorenzo and Ruta Michele, 2024. “Trade Spillovers of Domestic Subsidies.” IMF Working Paper 2024/041, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC

[9] Arnold, Nathaniel, Guillaume Claveres, and Jan Frie. Forthcoming. “Stepping Up Venture Capital to Finance Innovation in Europe.” IMF Working Paper, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

[10] Head, Keith, and Thierry Mayer. 2021. “The United States of Europe: A Gravity Model Evaluation of the Four Freedoms.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 35 (2): 23–48.

IMF Communications Department

MEDIA RELATIONS

PRESS OFFICER:

Phone: +1 202 623-7100Email: MEDIA@IMF.org