Soldiers on a street in Sanaa, Yemen, May 6, 2020 (photo: Chine Nouvelle/SIPA/Newscom)

COVID-19 Poses Formidable Threat for Fragile States in the Middle East and North Africa

May 13, 2020

All countries are struggling with COVID-19, but the threat is even more alarming for countries that are fragile and in conflict situations. A swift, coordinated response from the international community is necessary to avoid the worst.

COVID-19 will trigger a sharp drop in household incomes in Middle East and North African (MENA) countries that are fragile and in conflict situations, such as Afghanistan, Djibouti, Iraq, Lebanon, Sudan, and Somalia. As export earnings suffer and social distancing reduces domestic activity, incomes will decline—especially for informal and low-skilled workers, including within large internally displaced populations and refugees.

Related Links

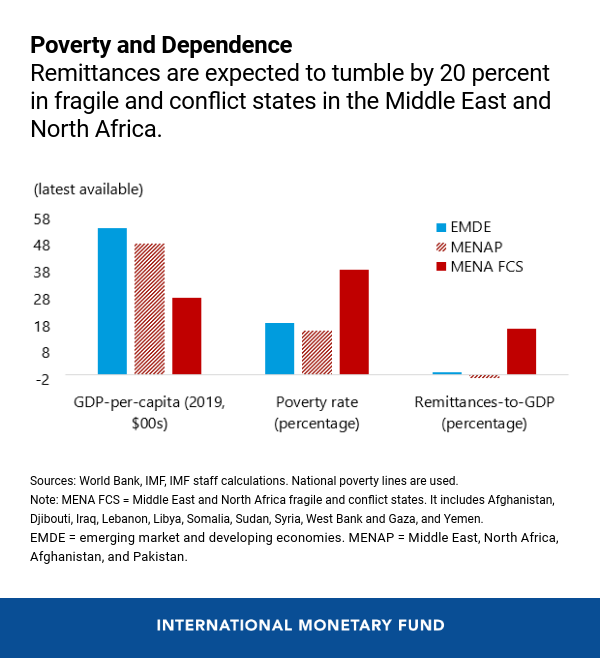

Remittances—which represent 14 percent of GDP in fragile countries across MENA and serve as a lifeline for many households—are also expected to tumble by 20 percent as global incomes fall.

More broadly, real GDP in these countries is expected to shrink by 7 percent in 2020, relative to average growth of 2.6 percent in 2019. This will lead to a significant decline in GDP per capita—from $2,900 in 2018–19 to $2,100 in 2020.

This dramatic downturn will aggravate existing economic and human challenges. Fragile and conflict countries in MENA are already battling high poverty, political instability, weak states, and poor infrastructure. Failure to ease the potential suffering could further aggravate underlying social and political instability and could trigger a reinforcing spiral of economic hardship and conflict—adding to the existing humanitarian challenges of countries already in active conflict, including Libya, Syria, and Yemen.

Protecting lives and livelihoods will be a tremendous challenge

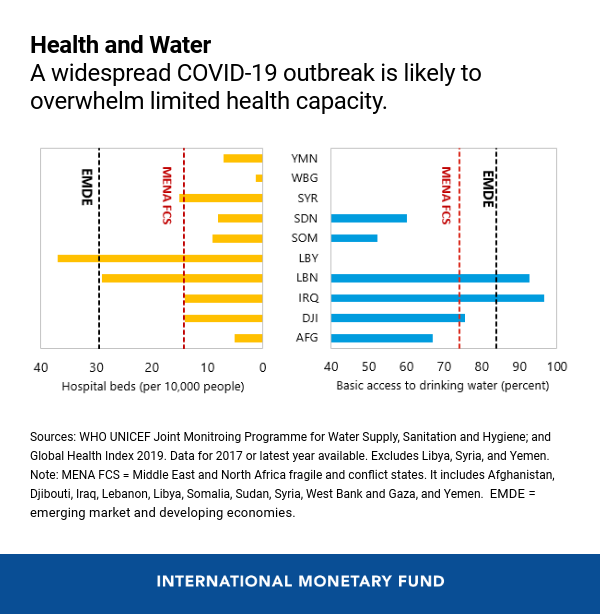

A widespread COVID-19 outbreak is likely to overwhelm limited health capacity. Fragile and conflict countries in MENA suffer a shortage of medical doctors (8 per 10,000 people compared to 14 in emerging market and developing economies). They also face a lack of hospital beds and limited access to handwashing facilities, drinking water, and sanitation, rendering individual protection against the virus an uphill battle. Shortages, due to reduced imports and international competition for medical equipment, will stress vulnerabilities even further.

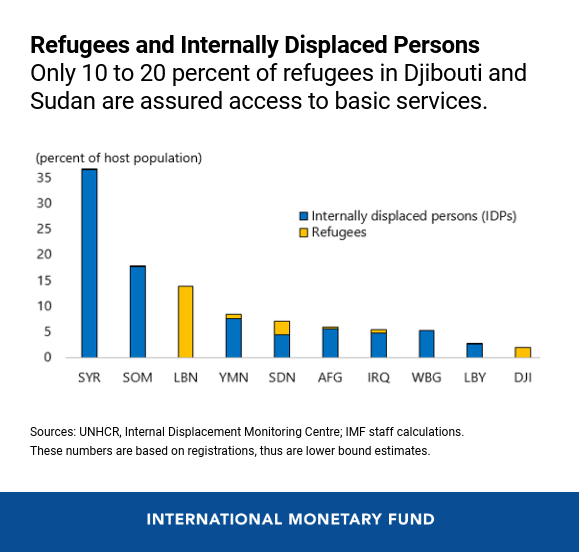

For a large share of the population, containing the virus might not be feasible. Together, these countries on the edge have 17.2 million internally displaced people and host a total of 2.7 million refugees. Many of these populations live in camps or other precarious conditions, where overcrowding and lack of proper sanitation and water could result in a rapid spread of the virus. For example, only 10 to 20 percent of refugees in Djibouti and Sudan are assured access to such basic services.

High levels of food insecurity further compound the health and poverty challenges. Food supplies are being affected by the impact of transport restrictions, while a range of climate change shocks such as droughts, floods, and a desert locust swarm have affected production and prices in some areas.

Poverty rates and economic disruption will worsen in the absence of a fiscal response, but the scope for such action is limited by already-scarce and fast-depleting resources.

A rapid, global response is vital

Swift international support is essential to provide critical medical equipment and support the necessary increase in health spending, as well as to provide some social protection and economic support to lessen the human hardship. This will help these fragile countries to avoid the worst, including a potential increase in conflict.

The international community also has a part to play in helping fragile countries allocate these extra resources across communities in the best possible way. This would help reduce the risk that an unequal distribution of human and economic losses across political factions and communities fuels tensions, insecurity and localized violence—as observed in countries affected by the Ebola outbreak. A thoughtful distribution of resources also reduces the risk that refugees or the internally displaced may be accused of spreading the disease.

Along with other international financial institutions, the IMF is providing policy advice and support to help address the economic challenges, with Afghanistan, Djibouti, and Yemen already benefitting from emergency financing and/or debt relief. In parallel, the United Nations has begun mobilizing resources for a $2 billion response plan and has called for a global ceasefire—critical to allow for a proper medical response.

“Forceful action now will protect hard-earned progress on reforms in some countries and avoid a new humanitarian crisis, reducing the twin risk of future demands for international aid and increased refugee flows,” said Jihad Azour, Director of the Middle East and Central Asia Department.

Turning crisis into opportunity

With adequate support, countries on the brink could transform this crisis into an opportunity. The COVID-19 crisis, together with the risk of a second wave, constitute a call for action to establish basic health and social protection capacities, to better integrate refugees, and to build greater credibility of the state. All of which will strengthen the foundation for social and political stability moving forward.

The crisis could also accelerate the push towards greater digitalization, generating broader gains in areas such as transparency, efficiency of public service, and tax administration. Increased formalization of the economy is also possible, which would improve people and firms’ future access to commodities, services, finance and markets.