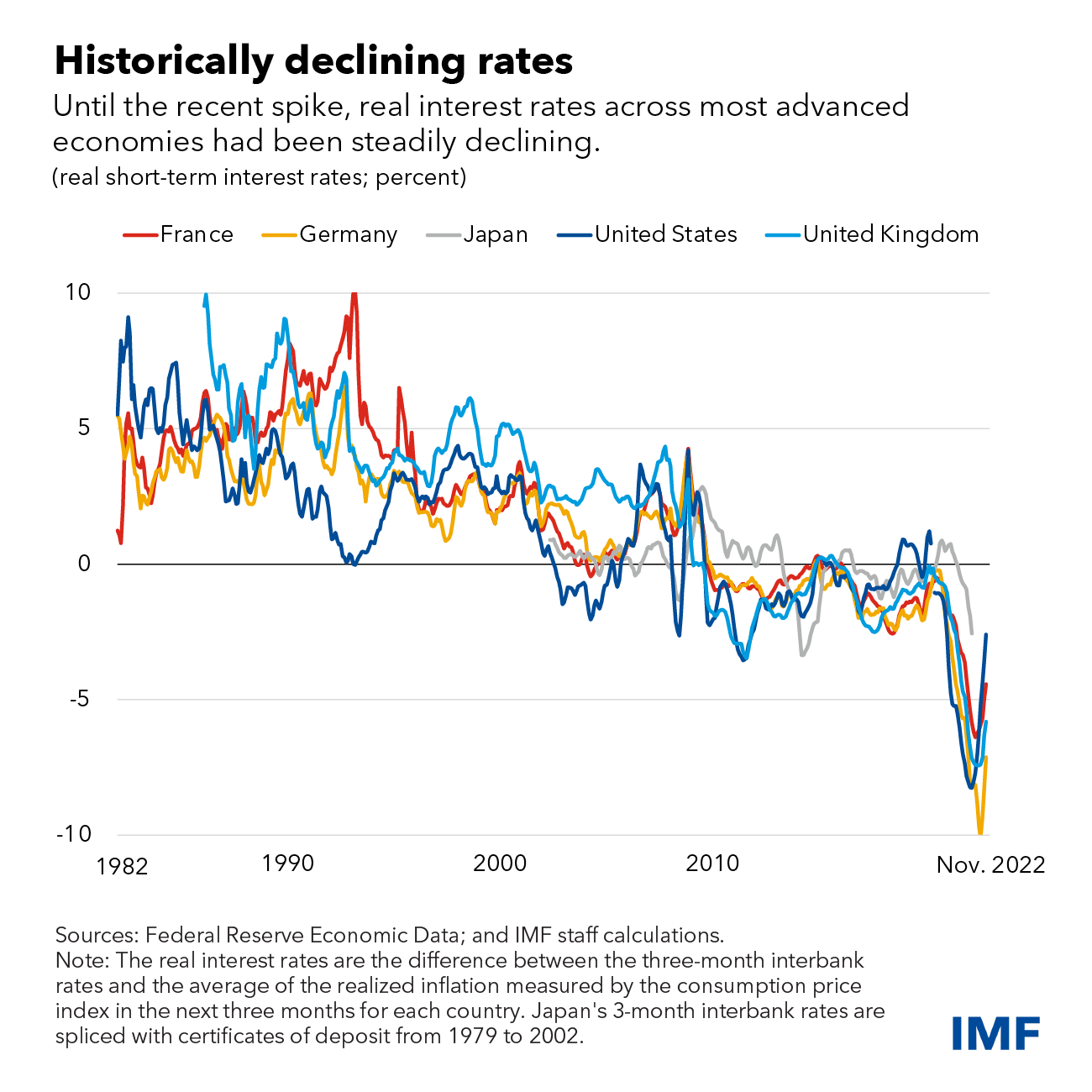

Real interest rates have rapidly increased recently as monetary policy has tightened in response to higher inflation. Whether this uptick is temporary or partly reflects structural factors is an important question for policymakers.

Since the mid-1980s, real interest rates at all maturities and across most advanced economies have been steadily declining. Such long-run changes in real rates likely reflect a decline in the natural rate, which is the real interest rate that would keep inflation at target and the economy operating at full employment–neither expansionary nor contractionary.

The natural rate is a reference point for central banks that use it to

gauge the stance of monetary policy. It is also important for fiscal

policy. Because governments typically pay back debt over decades, the

natural rate—the anchor for real rates in the long term—helps determine the

cost of borrowing and the sustainability of public debts.

In an analytical chapter of our latest World Economic Outlook, we explore what forces have driven the natural rate in the past and what is the most likely future path for real interest rates in advanced and emerging market economies, based on the outlook for these factors.

Historical drivers of natural rates

An important question when analyzing past synchronized declines in real interest rates is how much they were driven by domestic as opposed to global forces. Does productivity growth in China and the rest of the world, for instance, matter for real interest rates in the United States?

Our analysis concludes that global forces matter, but that their net effect on the natural rate has been relatively modest. Fast growing emerging market economies acted as a magnet for advanced economies’ savings, lifting their natural rate up as investors took advantage of higher rates of return abroad. However, because savings in emerging markets accumulated faster than these countries’ ability to provide safe and liquid assets, much of it was reinvested in advanced economies’ government securities—such as US Treasuries—pushing their natural rate back down, especially since the global financial crisis in 2008.

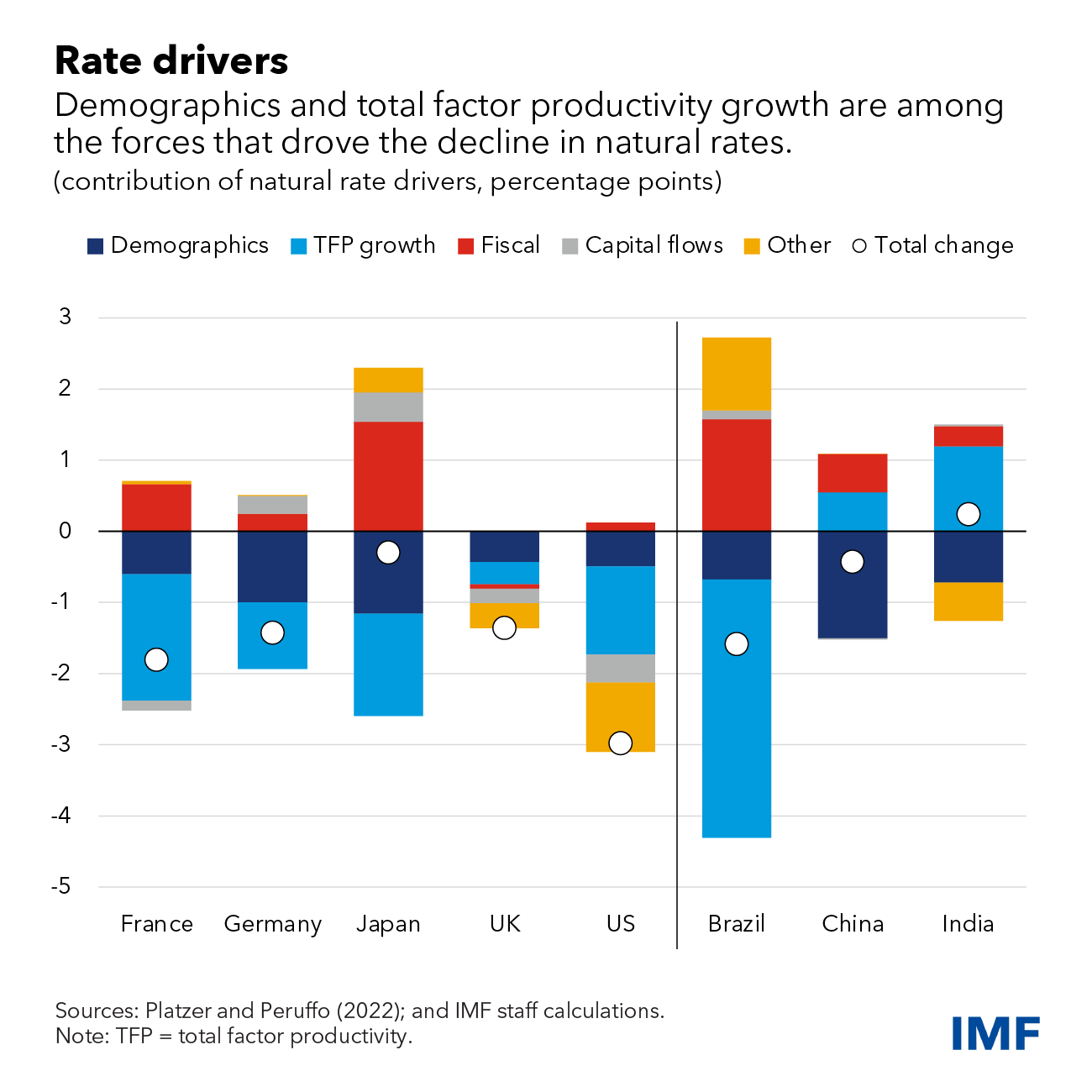

To investigate this issue in more depth, we use a detailed structural model to identify the most important forces that can explain comovement in natural rates over the past 40 years. On top of global forces that impact net capital flows, we find that total factor productivity growth (the total amount of output produced with all factor inputs in the economy) and demographic forces, such as changes in fertility and mortality rates or time spent in retirement, are major drivers of the decline in natural rates.

Higher fiscal financing needs have pushed up real rates in some

countries, like in Japan and Brazil. Other factors, such as the increase in

inequality or drop in labor shares have also played a role, but to a lesser

extent. In emerging markets, the picture is more mixed with some countries,

like India, seeing an increase in the natural rate over the period.

Outlook for real interest rates

These factors are not likely to behave very differently in the future, so natural rates in advanced economies will likely remain low. As emerging market economies adopt more advanced technology, total factor productivity growth is expected to converge to the pace of advanced economies. When combined with an aging population, natural rates in emerging market economies are projected to decline towards advanced economies’ rates over the long term.

Of course, this projection is as good as the projection of the underlying drivers. In the current post-pandemic context, alternative assumptions could be relevant:

- Government support may be difficult to withdraw, increasing public debt.

As a result, so-called convenience yields—the premium paid by investors in

the form of foregone interest for holding scarce, safe, and liquid

government debt—may erode, raising natural rates in the process.

- Transitioning to a cleaner economy in a budget neutral way would tend to

push global natural rates lower in the medium term, as higher energy prices

(reflecting a combination of taxes and regulations) would bring down the

marginal productivity of capital. However, deficit-financing of public

investment in green infrastructure and subsidies could potentially offset

and even reverse this result.

- Deglobalization forces could intensify, leading to both trade and financial fragmentation, and bringing the natural rate up in advanced economies and down in emerging market economies.

Individually these scenarios would have only limited effects on the natural rate but a combination, especially of the first and third scenarios, could have a significant impact in the long run.

Overall, our analysis suggests that recent increases in real interest rates are likely to be temporary. When inflation is brought back under control, advanced economies’ central banks are likely to ease monetary policy and bring real interest rates back towards pre-pandemic levels. How close to those levels will depend on whether alternative scenarios involving persistently higher government debt and deficits, or financial fragmentation materialize. In large emerging markets, conservative projections of future demographic and productivity trends suggest a gradual convergence towards advanced economies’ real interest rates.

This blog is based on Chapter 2 of the April 2023 World Economic Outlook,“The Natural Rate of Interest: Drivers and Implications for Policy." The authors of the chapter are Philip Barrett (co-lead), Christoffer Koch, Jean-Marc Natal (co-lead), Diaa Noureldin, and Josef Platzer, with support from Yaniv Cohen and Cynthia Nyakeri.