Sub-Saharan African countries will need to implement targeted policy actions to reduce profit shifting in the mining sector and avoid losses in tax revenue.

Sub-Saharan Africa is estimated to possess 30 percent of global mineral reserves, representing a major opportunity for the region. Despite the high level of private investment in this critical sector, new analysis finds that many multinational companies are avoiding paying their taxes.

Targeted policy actions to reduce tax avoidance could help governments recover some of this badly needed tax revenue.

To get a sense of the scale of the investment that companies are making in the region’s mining sector consider the case of Guinea. One multinational company has invested five times more in a single bauxite mine (as a percent of GDP) than the government has spent in total public investment since 2018.

New IMF staff research shows that governments in sub-Saharan Africa—now under tremendous pressure to raise public spending in response to the pandemic—are losing between $450 and $730 million per year in corporate income tax revenues as the result of profit shifting by multinational companies in the mining sector. Targeted policy actions to reduce tax avoidance could help governments recover some of this badly needed tax revenue to aid with the recovery and meet Sustainable Development Goals.

Our analysis comes amid a global effort to address tax competition and profit shifting by multinational companies, which has put unprecedented stress on the international corporate tax system. To address this, 136 countries, including 20 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, agreed last month to a minimum effective corporate tax rate of 15 percent starting in 2023.

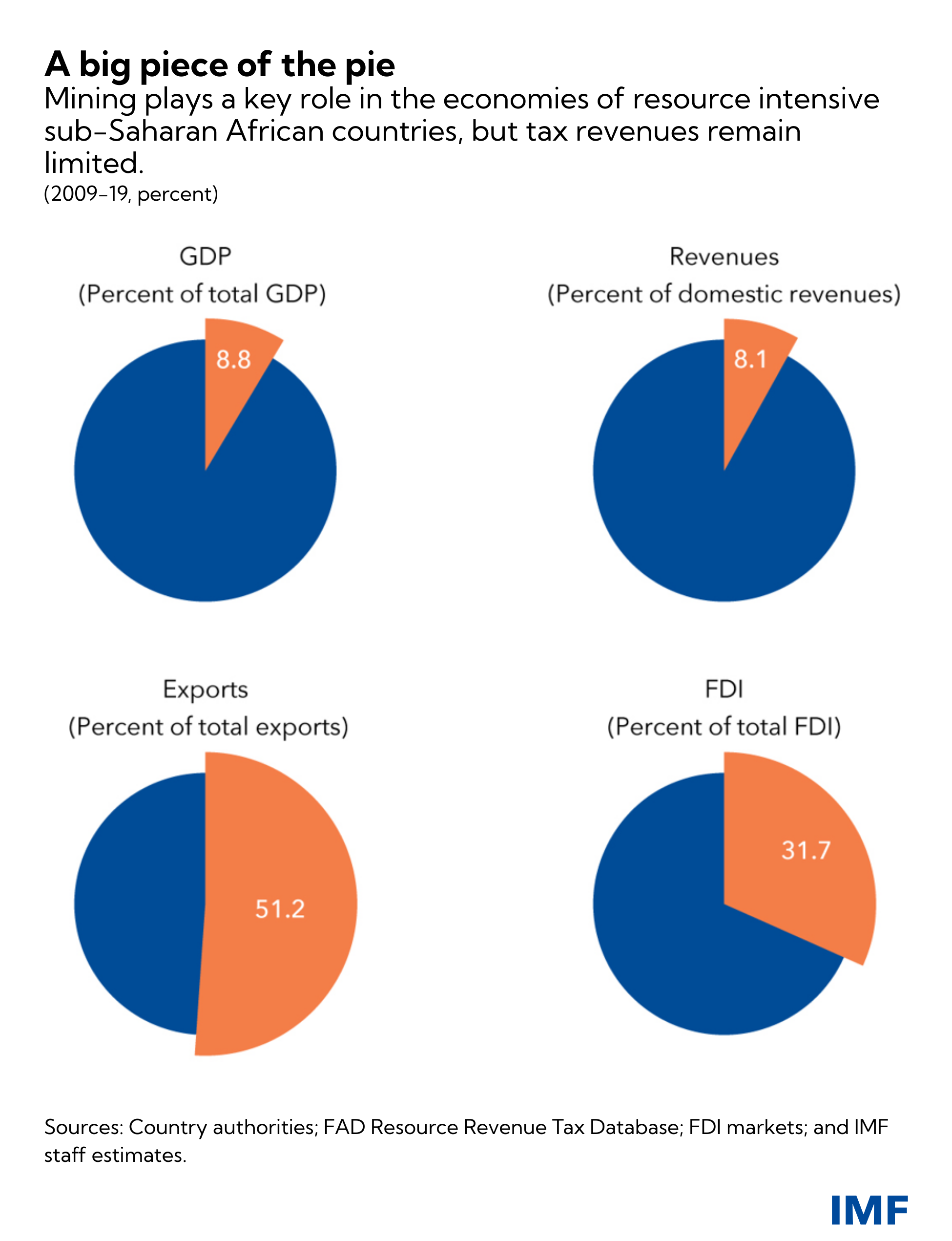

The importance of mining to economies in the region is clear. The mining sector contributes about 10 percent to GDP across 15 resource intensive sub-Saharan African countries. In most of these countries, mining exports represent 50 percent of total exports on average and is the main source of foreign direct investment.

However, for the 15 resource-intensive economies in the region, revenue from mining accounts for just 2 percent of GDP on average. There are concerns that this level of revenue does not represent a “fair” sharing of the benefits.

Our research found that revenues are being reduced in two ways. First, countries try to attract inbound investment by lowering taxes, which has stoked unhealthy regional tax competition. Second, international profit shifting by multinational companies has reduced the tax base in producing countries.

An effective fiscal regime

Most countries in Africa collect revenues from the mining industry through a combination of royalties, corporate income tax, and sometimes the state taking a non-controlling ownership stake in projects where they receive dividends from corporate profits.

The structure of mining fiscal regimes in the region directly affects the pattern and magnitude of revenue from mining. Furthermore, governments have reduced corporate income tax rates in many sectors, including mining, amid competition to attract investment and efforts to boost economic development.

Our research highlights that out of the 15 resource-intensive economies in sub-Saharan Africa, only three had lower corporate income tax rates for mining in their tax law, and six had higher tax rates for the sector. However, the practice of negotiating down corporate income tax rates in contracts with individual mining projects is widespread. At least nine countries have reduced ad-hoc corporate income tax rates as an incentive in at least one resource contract with investors. This has led to a lower effective corporate tax rate in the mining sector compared to statutory rates.

Playing the shell game

Our research also shows that international profit shifting is having a dramatic effect on collected revenues. Multinational companies use their global reach to reduce tax liabilities in high-tax jurisdictions by shifting profits to lower-tax countries. One example is the use of an interest-bearing loan arranged between the different entities within a multinational company. The interest expenses are claimed as a deduction in the higher tax country (Africa) while interest income is allocated to a lower-tax country offshore. Other examples include underpricing minerals or using subcontractors to move profits offshore.

Our analysis of payments data, reports from the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, an internal IMF resource revenue data set, and financial information from more than 600 multinational companies reveals that an increase in the corporate income tax rate differential between the (higher) producing country and the average (lower) offshore countries by 1 percentage point results in a decrease of reported profits in the mining sector by 3.5 percent.

Building on this research, African countries are estimated to be losing about $450–730 million in corporate income tax revenue a year on average from tax avoidance by multinational mining companies.

Stanching the flow

Targeted policy actions can help countries reduce tax avoidance in the mining sector and foster revenue mobilization. A concerted effort to close off current profit shifting channels could pay dividends. Recommended actions include strengthening and simplifying transfer pricing protection, limiting interest deductions, improving tax treaty practices, limiting tax incentives, and strengthening investment negotiation practices. In our research, imposing interest limitation rules halved the responsiveness of profit allocation by multinational companies as a response to international tax rate differentials.

Some countries are already making progress in addressing profit shifting in the mining sector. Sierra Leone’s new fiscal regime moved the country away from negotiating fiscal terms mine by mine; Guinea, Liberia, and Mali have strengthened their transfer pricing protection; South Africa and Nigeria have set limits on interest deductions; nine of the 15 resource intensive economies have alternative minimum taxes that can ensure at least some corporate taxes are paid each year, and Kenya introduced an anti-treaty shopping provision into its tax treaty policy.

These actions hold the promise of stronger revenue mobilization from mining in sub-Saharan Africa. And the global minimum tax will likely mitigate profit shifting and reduce pressures from tax competition. Improving tax policy and tackling tax avoidance require careful preparation and stronger capacity, which take time, resources, and political commitment, but recent international tax developments show that change is possible.