Commitment to budget discipline and clear communication of policy priorities pays off.

Ending the health crisis and addressing its immediate fallout remains the top priority, but governments would also benefit from committing to fiscal responsibility. From the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, governments have extended massive fiscal support that has saved lives and jobs. As a result, public debt has reached a historic high, although it is expected to decrease marginally in the next few years. These developments raise questions about how high debt can go without being disruptive.

Addressing the health emergency remains crucial, especially in countries where the pandemic is not yet under control, and fiscal support will be invaluable until the recovery is on a strong footing. The appropriate timing for starting to reduce deficits and debt will depend on country-specific conditions.

But governments also need to consider fiscal risks and the vulnerability to future crises. Fortunately, interest rates have been very low globally. But there is no guarantee this will last.

Greater predictability

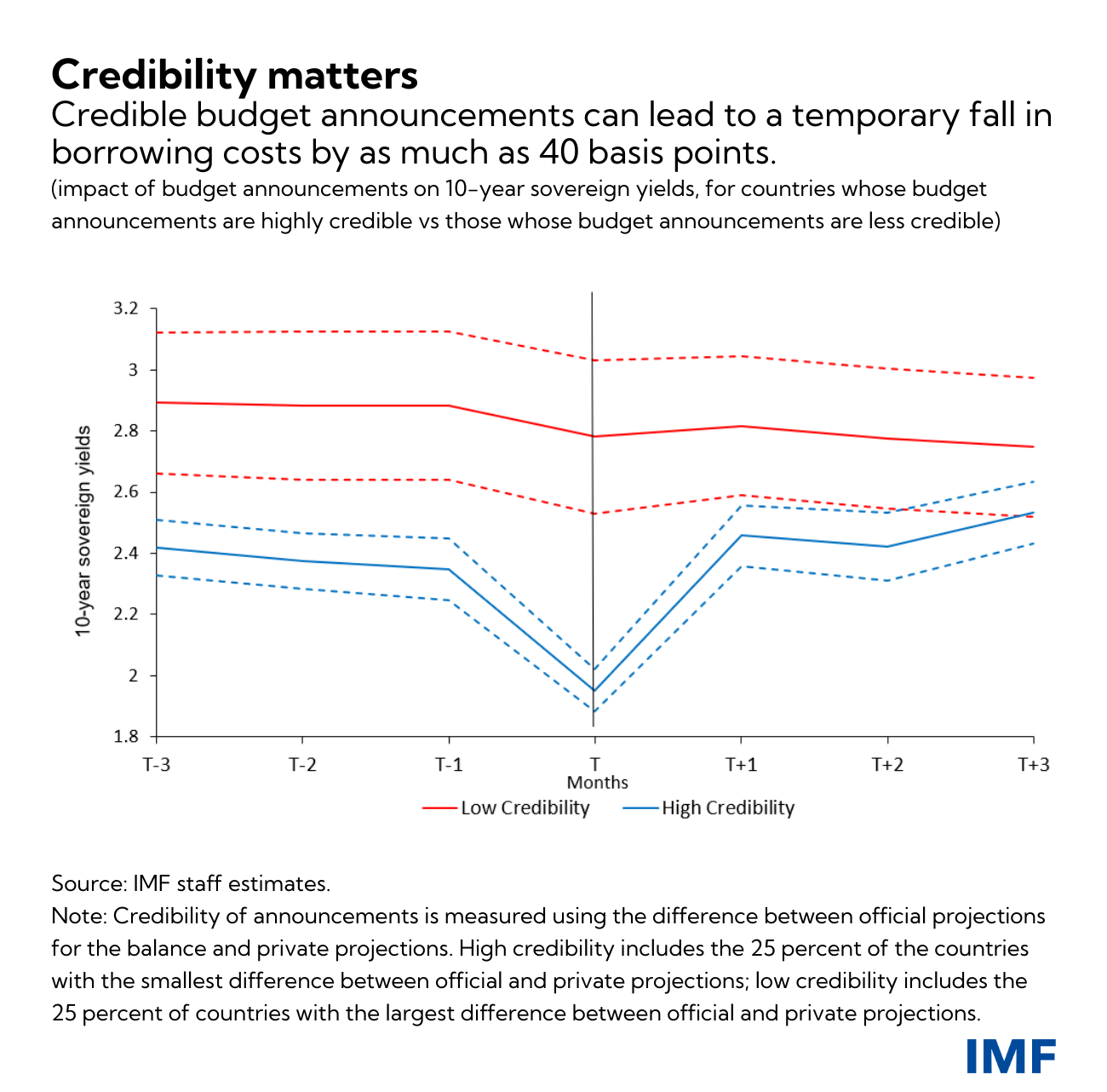

Our new Fiscal Monitor argues that committing to sound public finances, with a credible set of rules and institutions to guide fiscal policy, can facilitate fiscal policy decisions at the current juncture. When lenders trust that governments are fiscally responsible, they make it easier and cheaper for countries to finance deficits. This buys time and makes debt stabilization less painful. For instance, when budget plans are credible (as measured by how close professional forecasters’ projections are to official announcements), borrowing costs can fall temporarily by as much as 40 basis points. And even for governments that do not borrow from markets, fiscal credibility can attract private investment and foster macroeconomic stability.

Governments can signal their commitment to fiscal sustainability while addressing the ongoing crisis in various ways, such as undertaking structural fiscal reforms (for example, subsidy or pension reform) or adopting budget rules and establishing institutions that are geared toward promoting fiscal prudence.

Unwelcome debt increases

When governments conceive and put in place budget rules and institutions, they should strive to consider all risks to the public finances. Debt sometimes increases beyond what is forecast in the baseline. These jumps typically range between 12 and 16 percent of GDP at five-year projection horizons, our research shows. Underlying such negative shocks are disappointing medium-term GDP growth and other drivers of debt, including bailouts of businesses and exchange rate depreciation. Many countries now face heightened fiscal risks as a result of record loans, guarantees, and other measures taken to protect firms and jobs from the fallout of COVID-19.

Such shocks put pressure on budgets and fiscal institutions such as fiscal rules, which need to be flexible to allow for larger deficits when needed. Well-designed risk mitigation strategies—such as restrictions on loan eligibility or limits on loan size and maturity—can reduce these risks, or limit fiscal costs if they materialize. But these frameworks must also ensure steadfast debt reduction in good times, so that fiscal support can be deployed again in the future.

Budgetary rules and institutions

A robust set of budgetary rules and institutions should seek to achieve three overarching goals: sustainability; economic stabilization; and, for fiscal rules in particular, simplicity. However, it is difficult to fulfill all three goals at once.

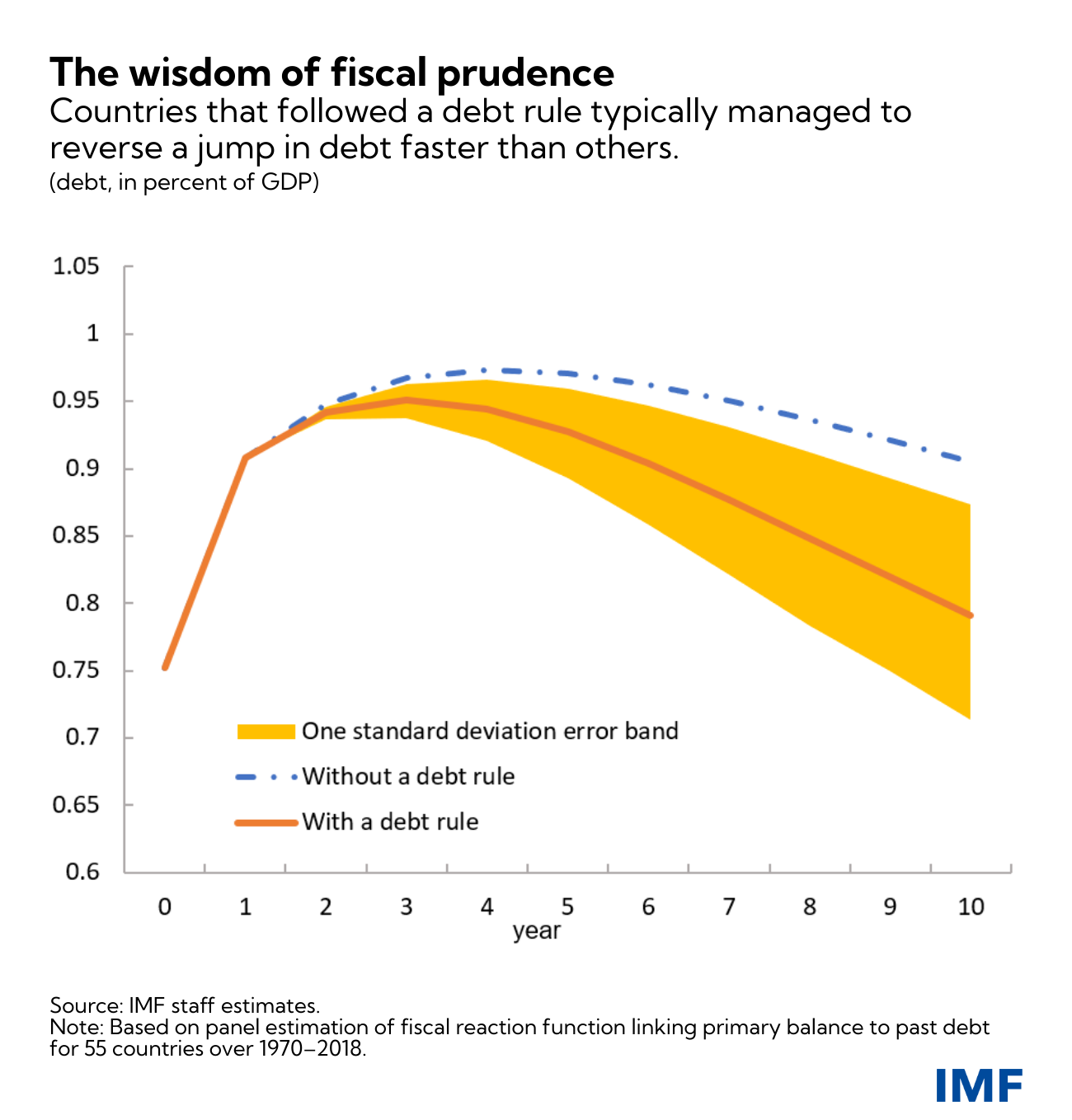

Although simple numerical rules can sometimes be rigid, we show that they promote fiscal prudence. For instance, countries that follow debt rules generally manage to reverse debt jumps of 15 percent of GDP in about 10 years in the absence of new shocks—significantly faster than countries that do not follow debt rules. Numerical rules need not rely only on debt: other indicators, such as the interest bill or the net worth of the government, can complement traditional debt and deficit indicators. Procedural rules offer more flexibility than numerical fiscal rules, but it may be harder for governments to communicate and monitor compliance without numerical targets, particularly in the absence of sound fiscal institutions.

Our research shows that a country’s commitment to budget discipline and clear communication of policy priorities—backed by transparency about government spending and revenues—pays off. Many countries suspended their fiscal rules in 2020 so as to rightly increase health care and social spending to address the pandemic. Our analysis of newspapers shows that media reporting of the suspension of fiscal rules was more positive in places with higher fiscal transparency.

Strong budget rules and institutions, backed by clear communication and fiscal transparency, enhance credibility. That, in turn, improves access to credit and secures more room for maneuver in times of crisis. Ultimately, fiscal frameworks are only effective if they have sufficient political support. Even so, they help focus discussions and can thus help reach political consensus on credible fiscal policies.