June 21, 2018

Versions in Español, Português

[caption id="attachment_23795" align="alignnone" width="1024"] People buying produce in a busy market in Bahia, Brazil. During the commodity boom, Brazil saw significant reductions in poverty and inequality (photo: golero/iStock by Getty Images)[/caption]

People buying produce in a busy market in Bahia, Brazil. During the commodity boom, Brazil saw significant reductions in poverty and inequality (photo: golero/iStock by Getty Images)[/caption]

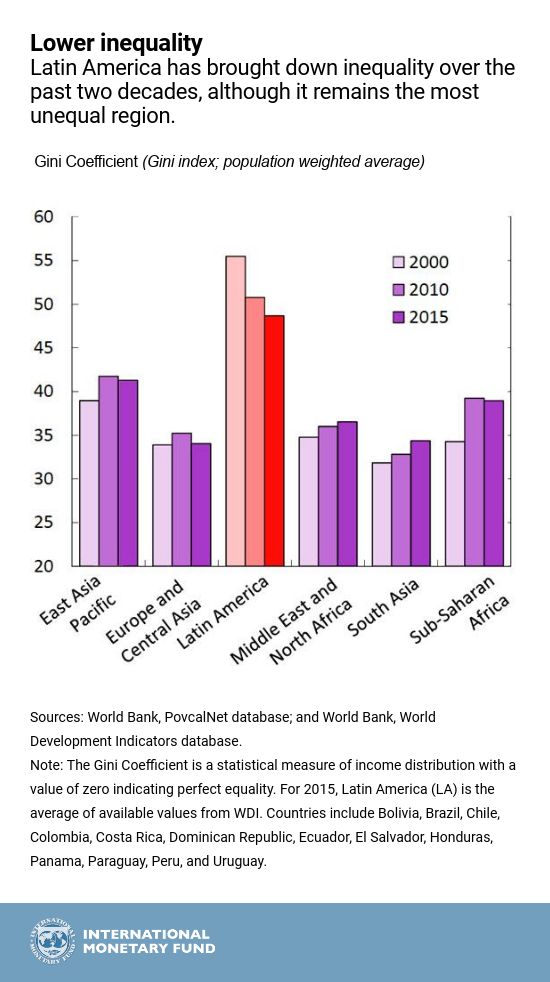

Latin America may be the most unequal region in the world, but it is the only region to significantly lower inequality over the past two decades, and the boom in commodity prices helped make it happen.

With the boom over, poverty rates are edging up in some Latin American countries, and job creation has slowed. The region needs to find new ways to raise its currently low revenue collection and allow for further spending on key social areas, such as education and healthcare. This will help sustain growth and fight inequality and poverty.

Benefits of a boom, especially for South America

In our latest Regional Economic Outlook for Latin America, we show that poverty has decreased from about 27 to 12 percent, and inequality has decreased almost 11 percent across Latin America from 2000 to 2014. This period, commonly referred to as the commodity boom, saw the prices of commodities like oil, and metals, steadily increase thanks to growing demand from emerging market economies like China and India.

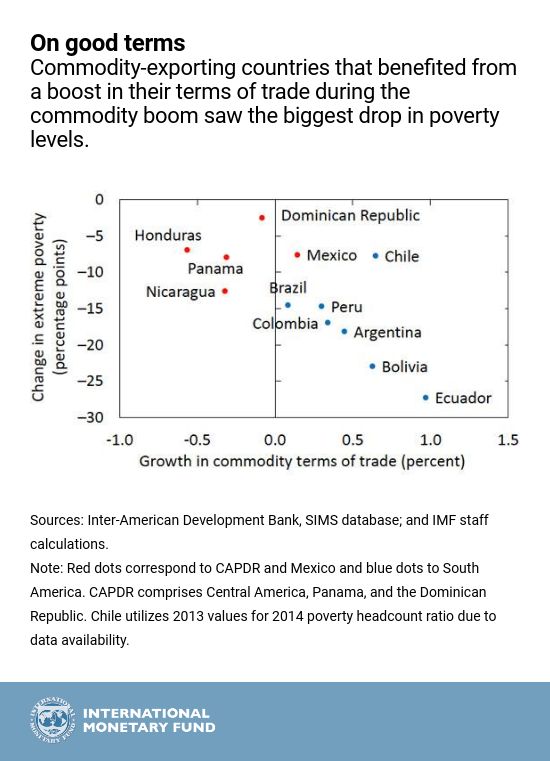

During the commodity boom, South America, home to many commodity exporters, experienced a significant boost in its terms of trade—the price of their exports relative to the price of their imports. And many of South America’s commodity-exporting countries, like Bolivia, Brazil, and Peru also saw the strongest declines in poverty and inequality.

For poverty specifically, commodity exporters experienced larger reductions than commodity importers across the board, except for Chile (which already had a low level of poverty) and Honduras, which experienced smaller improvements than some non-commodity exporters, such as Nicaragua and Panama.

How did this happen? The booming commodity sector expanded and drew in labor, raising wages and employment. The demand for more workers also spilled over to other sectors, such as construction. At the same time, government revenues increased, which supported higher public investment and spurred job creation.

This resulted in commodity exporters seeing significantly larger real labor income and employment gains than non-commodity exporters. And since lower-skilled workers gained the most, poverty and inequality fell. Importantly, some governments used their higher revenues to increase social transfers to lower-income groups—such as the non-contributory pensions Renta Dignidad in Bolivia and Pension 65 in Peru, and the conditional cash-transfer program Bolsa Familia in Brazil—further reducing poverty and inequality.

Overall, given that labor income accounts for a much larger fraction of overall household income than government transfers, labor income gains played a larger role in poverty and inequality reduction in general.

Redistributing gains to regions which produce natural resources

Rather than spending at the central government level, several commodity-exporting countries such as Bolivia, Brazil, and Peru redistributed large parts of their earnings from natural resource extraction back to municipalities and regions where resource extraction is located.

And looking at municipalities in Bolivia and Brazil, we find that poverty fell somewhat more in those with larger natural resource-related fiscal transfers, such as shares in royalties and other commodity-related taxes.

But, there are several potential drawbacks to doing this. First, in both Peru and Bolivia, some local governments with the biggest windfalls per capita began to accumulate large deposits during the boom, while acute investment needs existed in other regions with poor infrastructure and high levels of poverty.

Second, the volatile nature of commodity revenues makes them a challenge to manage even at the central government level, something which is amplified at the local level by weaker institutions and less qualified staff.

This difficulty can be seen in the most important commodity-producing regions in Bolivia and Brazil, Tarija and Rio de Janeiro, respectively. They received huge commodity-related fiscal transfers during the boom but since the end of the boom, they have faced serious budgetary pressures as their revenues collapsed.

Poverty has decreased from about 27 to 12 percent across Latin America.

Managing the impact of lower commodity prices

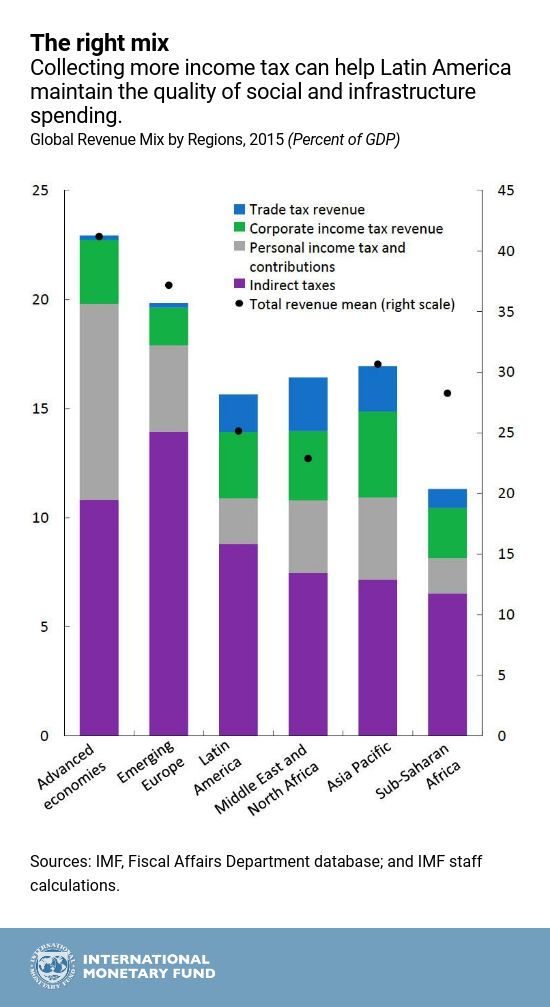

We find that to maintain the quality of social and infrastructure spending, governments in the region will need to raise more revenue and spend more efficiently. This is important since Latin America already spends significantly less on social protection than emerging market economies in Europe or advanced economies.

To do this, countries can:

- Increase revenues from progressive personal income taxes, which tend to be less in Latin America compared to other regions.

- Reduce energy subsidies, which typically benefit the rich far more than the poor.

- Better target existing social spending, and make sure other spending is not being wasted.

- Take greater account of spending needs (for example, population size and poverty levels) when transferring fiscal resources associated with production of commodities to regions and municipalities.

- Consider greater use of stabilization funds for volatile natural resource revenues, with clear rules and governance arrangements.

- Continue enhancing capacity at the local level. For example, further training local government staff, making sure they have access to the right technologies and trying to avoid excessive staff turn-over.

And since better education played an important role in reducing inequality and lifting people out of poverty during the boom, improving the quality of education will be critical to supporting further progress in a post-boom world.